London dance music radio station Kiss FM has re-scheduled its specialist shows to slots after midnight, according to The Guardian, and has cut their duration from two hours to one hour. Almost nobody listens to radio on a weekday after midnight, RAJAR audience data show, so the policy change condemns these shows to a radio graveyard that is very close to extinction.

According to Kiss FM specialist DJ Logan Sama: “The shift of focus away from upfront specialist music to more playlisted hours is one which the management feel will enable the station to compete with the likes of Capital and Galaxy FM. All of the genre-specific late-night shows took the brunt of the hit.”

When Kiss FM was launched in 1990, its specialist music shows started at 7.30pm on weekdays, and the preceding half-hour magazine show ‘The Word’ created a watershed between the daytime mainstream playlist and the more radical evening shows. There was a specific commitment in the station’s licence to broadcast these shows so that Kiss FM would give airplay to music unheard anywhere else on the radio in London.

In the intervening years, through attrition, Kiss FM’s owner (EMAP then, Bauer now) has succeeded in ‘persuading’ the regulator to loosen these licence requirements for the station to broadcast specialist music shows. To its discredit, the regulator has seemed happy to go along with such proposals, permitting Kiss FM to be turned into a much more mainstream hit-orientated station than it was ever intended to be.

What the regulator and some radio owners seem to fail to grasp is that, in a crowded radio market such as London, one station can attract a significant (and loyal) audience by doing something deliberately different both from its competitors and from its own daytime mass-market output. This works both commercially and altruistically. In the case of Kiss FM, advertisers can reach a niche audience that daytime shows do not deliver (if I organise a reggae concert, the best place to advertise it is in a reggae radio show); citizens are offered a genuine extension to the ‘listener choice’ that the regulator loves to cite.

This is not just a theory – there is plenty of empirical evidence to demonstrate how it works. Look at Helen Mayhew’s evening ‘Dinner Jazz’ show on the original London Jazz FM, which was almost the only show on the station that delivered 100% jazz music, but also had higher ratings than any of the daytime playlisted output.

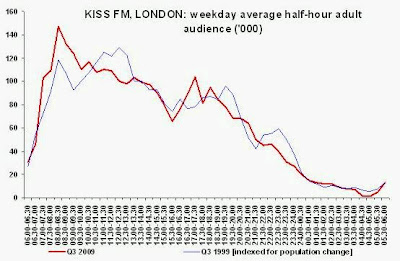

Kiss FM itself provides a good example of what can be achieved. In the graph above, the red line shows the current audience of Kiss FM London (RAJAR, Q3 2009) peaking at 147,000 adults at breakfast between 8 and 8.30am, then falling to a minimum of 1,000 adults by the early hours of the next morning. This is the normal pattern of listening for a mainstream music radio station in the UK.

The blue line shows the Kiss FM London audience a decade earlier in 1999 when specialist music shows still occupied the weekday evening hours. Note that, in the evening, during most of the hours from 7pm to midnight, the audience was bigger a decade ago than it is now. Has the subsequent replacement of specialist music shows with mainstream music in the evening improved Kiss FM’s audience at those times? Apparently not.

After the station launched in 1990, the daytime audience was lower than it is now, but the evening specialist music programmes generated huge audiences. Some of the Kiss FM evening shows attracted more listeners than any other London station in these evening timeslots, ranking them #1 in that daypart.

This was not an accident. Kiss FM’s original schedule was deliberately designed to attract significant audiences to each of a wide range of specialist music shows broadcast on weekday evenings. Listeners loved them – individual shows were promoted heavily on-air and in specialist music magazines. Advertisers loved them – the rates were cheaper than daytime and the spots regularly sold out.

Doing something different on-air can reap rewards, if you satisfy genuine listener demand and promote the hell out of it, so that people know the programmes are there. But, if you simply do the same in the evening that you are doing during daytime, your station is going to have much the same declining listening pattern as any other radio station.

If you compare Kiss FM’s current listening pattern to that of its competitors, you can see from the graph above that it delivers much the same weekday shape – a continuous decline from a peak at breakfast. The exception amongst the London commercial stations is Magic’s unusual peak between 10 and 11pm. Why? Because it schedules ‘The Mellow Ten At Ten’ each weekday evening from 10pm, a one-hour feature that breaks from its playlist.

Also noteworthy in the graph is the unusually high evening audiences achieved by Choice, with more listeners than the station attracts during the afternoon. Why? Because Choice schedules specialist music shows during weekday evenings (mixes, reggae, hip hop). Again, being different can pay off for both audiences and advertisers.

This concept – that individual radio stations often struggle to sound the same, even though ‘daring to be different’ pays dividends – has been understood since the earliest days of media theory. American economist Peter Steiner wrote:

“…. the existence of [different] program types and [different] audiences therefor is assumed by the broadcasting industry and forms the basis for [station] program decisions. In this case, it is the assumed size and distribution of listeners’ preferences that is decisive in determining the amount of [programme] duplication that will result. If, as is often suspected, broadcasters exaggerate the homogeneity of audiences and their preferences for certain program stereotypes, the tendencies towards [programme] duplication will be increased.”

Writing in 1951, Steiner already recognised that radio station owners will tend to duplicate each others’ formats and programme scheduling, rather than offering their audiences something different or unique. He wrote:

“The problem, of course, is that a series of competing firms, each striving to maximize its number of listeners, will fail to achieve either the industry or the social good. Here, then, competition is providing a less than desirable result.”

In the UK, our government created a broadcast regulator to intervene in the market to ensure that commercial radio station formats maximise the ‘social good’, as Steiner refers to it. The UK is in a very different situation from the US, where the regulator (FCC) does not interfere in the formats of radio stations. But the UK system will only work if the regulator understands the economic and social imperatives for market intervention and exercises those powers appropriately.

The increasing marginalisation over the years of Kiss FM’s specialist music programmes demonstrates that the regulator is oblivious to the economic and social imperatives to regulate. Instead, it is simply conspiring to deny both listeners and advertisers the programme diversity they should be entitled to. The fact is that ‘light touch’ radio regulation is not regulation at all, any more than driving a car with no hands on the steering wheel would be considered by a court to be ‘driving’.

A regulator that simply allows market forces, in Steiner’s words, to produce “a less than desirable result” is not regulating. The Independent was quick to blame Kiss FM’s owner:

“Once the king of pirate radio, the legendary station Kiss is being dragged into the mainstream by owners Bauer Media, which will today cut back a number of the Kiss specialist music shows and axe several presenters in order to reposition the network to take on Global Radio operations such as Galaxy. Shame.”

However, the blame should fall squarely on the regulator for allowing a station owner to pursue an objective that further restricts consumer and advertiser choice. There is no ‘free market’ for radio in London – the gap in the market created by Kiss FM’s marginalisation of specialist music genres and DJs will not be filled by another licensed radio station …… only by London pirate stations.

Pirate radio stations seem to be the only ones that implicitly understand Steiner’s competition theories perfectly, and they risk the consequences for putting them into action. Pirate radio’s popularity is no accident – it is a direct outcome of the failure of the regulator to regulate.