The government’s forthcoming Digital Economy Bill will be the most significant legislation for the UK radio industry since the passage of the Communications Bill in 2002. Published at the end of November 2009, the Digital Economy Bill will propose ‘primary’ legislation that sets out a new regime for the licensing and regulation of commercial radio in all its forms – national analogue stations, local analogue stations and local DAB multiplexes.

The main thrust of the new legislation for commercial radio was contained in the Digital Britain final report published in June 2009. According to the Department of Culture Media & Sport, Lord Carter’s almost year-long consultation was intended to set out “the Government’s strategic vision for ensuring that the UK is at the leading edge of the global digital economy” and would introduce “policies to maximise the social and economic benefits from digital technologies”. Indeed, some of the changes proposed for the radio industry are forward-looking and designed to place the sector in a multimedia future in which it could survive and thrive.

However, some of the recommended changes to existing radio legislation are there only because parts of the commercial radio industry have lobbied for them to be there. At the time, these interested parties might have claimed that such changes would be beneficial to the commercial radio industry as a whole. Increasingly, other parts of that industry have realised that some Digital Britain proposals were lobbied for inclusion only because they suit the interests of a particular player, offering little or no benefit to the wider industry.

Worse, one proposal ties the future of the whole industry to a dangerous poker game with the government which commercial radio is unlikely to win. This is the Digital Britain proposal [page 102, paragraph 44] to automatically extend the existing licenses of the three national commercial radio stations for a further seven years. Why is this proposal there, and what does it have to do with the UK’s digital future? What price is the commercial radio industry being forced to pay for its inclusion?

During the Digital Britain consultation period, Global Radio had lobbied intensively to have the licence of its national analogue station, Classic FM, automatically renewed beyond its 2011 expiry date. In January 2009, I had written:

Classic FM’s licence expires on 30 September 2011 and it cannot be automatically renewed. This is a big problem. Whereas local commercial radio licences are still awarded (and re-awarded) by Ofcom under a ‘beauty contest’ system, national commercial radio licences are not. The system for national commercial radio licences is simple. Sealed bids are placed in envelopes. Ofcom opens the envelopes. The bidder willing to pay the highest price wins the licence. That’s it. This system is enshrined in legislation. Even if Ofcom wants a different system, it cannot change it without legislation.

As Classic FM’s new owner, Global Radio definitely wants a different system that will enable it to hang on to this most valuable asset. Global has been busy bending the ears of anybody and everybody who it might be able to persuade to interpret the broadcasting rules in a way that lets it keep Classic FM after 2011. Even Ofcom has had its lawyers busy examining the legislation to see what flexibility it has to interpret the rules in a way that might maintain the status quo.

Unfortunately, the legislation in the Broadcasting Act 1990 is quite specific:

“[Ofcom] shall, after considering all the cash bids submitted by the applicants for a national licence, award the licence to the applicant who submitted the highest bid.”

The solution for Global Radio was to lobby, lobby and lobby some more for the current legislation detailing the licensing system for national commercial radio to be revoked, changed, amended – whatever needed to be done to ensure that Global could hang on to its valuable Classic FM licence. When Digital Britain was published, it was evident that the phone calls and meetings had paid off handsomely. Lord Carter had listened and offered a solution – a significant change to primary legislation that would allow Global Radio to retain its Classic FM licence for a further seven years, replacing the existing legal requirement that it be re-awarded by Ofcom to the highest bidder in an auction in 2010.

Why exactly is Global Radio so desperate to hang on to Classic FM?

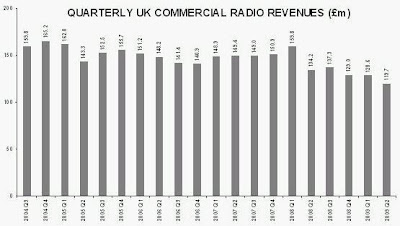

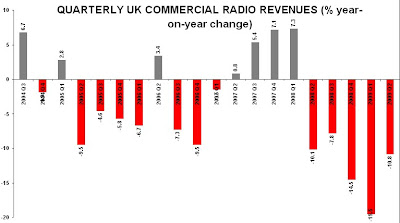

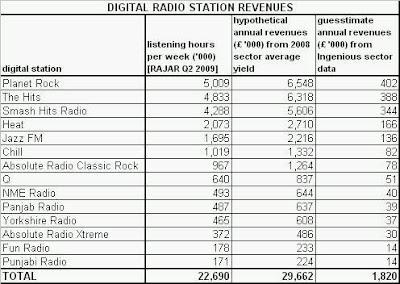

Firstly, Classic FM is a ‘cash cow’ and has always been the most successful of the UK’s three national commercial radio stations launched in the early 1990s. It attracts 40m hours listening per week which, at current sector yields, would earn it around £50m per annum revenues. However, its earning power is further enhanced by the affluence of its audience. Of its hours listened, 66% derive from ABC1 adults, 85% from ‘housewives’, and 68% from adults aged 55+, a target age group that very little commercial radio reaches. As a result, Classic FM is likely to be attracting more than 10% of total UK commercial radio revenues, significant for a single player out of 300 commercial stations. [RAJAR, Q3 2009]

Global Radio overpaid to acquire GCap Media for £375m in 2008. The challenge for Global is that the radio business is dominated by fixed costs. In other words, however many listeners an individual station has within its service area, that station’s costs are relatively static. Many of the stations in Global’s portfolio are medium-sized local operations, whereas Classic FM is a ‘giant’ with national coverage. Its profit margin probably far outstrips every other commercial station in the UK. Classic FM alone probably generates more operating profit than all Global’s other radio stations added together.

Classic FM occupies a unique position in the radio market (the only competitor in the classical music format is BBC Radio Three) and its market power has proven relatively stable over time, with a current listening share of 3.7%, only slightly down from 4.1% a decade ago. By comparison, GCap Media’s prime local radio assets also acquired by Global Radio have lost immense market power over the same period – the market share of London’s Capital FM down from 13.0% to 6.2%, and Birmingham’s BRMB down from 17.1% to 4.8%, for example. Thus, Classic FM is very much a ‘rock’ at a time many local commercial stations occupy a ‘hard place’. [RAJAR, Q3 2009 & Q3 1999]

Global Radio desperately does not want to partake in an auction for the Classic FM licence. It might under-bid and lose. It might over-bid and win. Either outcome would be a disaster, the former losing it the ‘crown jewels’, the latter allowing it to keep the licence but at a price that could lose the station its ‘cash cow’ status. Because there has been no auction of a national commercial radio licence auction since the early 1990s, nobody knows what the winning bid price might be. Worse, in the 1990s, the field had been open only to European Union companies. Legislation since then has opened up the bidding to the global market. Thus, a licence auction would be an extremely dangerous game for Global to play and, if it lost, would force it to write off its entire Classic FM balance sheet valuation only two years after it acquired the station.

Global Radio has a bargain on its hands in the current Classic FM licence. Not only does this one radio station attract more than a tenth of all commercial radio revenues, but its Ofcom-issued broadcast licence costs very little by market standards. The present cost is fixed at £50,000 per annum + 6% of revenues, probably amounting to around £3m per annum, not a huge expense for a station that generates around £50m. Why is the licence fee so little?

It is the regulator (initially the Radio Authority, now Ofcom) that sets the price of the licence, in the first instance according to the amount that the applicant has bid in its licence application to win the right to broadcast. The price of the licence is collected by the regulator but remitted directly to the Treasury in payment for the scarce FM radio spectrum used by the station.

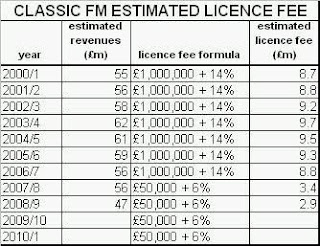

In 1991, when it won the licence at auction, Classic FM had bid £670,000 per annum plus 14% of its revenues. In 1999, the Radio Authority increased this to £1m per annum plus 14% of revenues. However, in 2006, Ofcom reviewed the Classic FM licence payment and slashed it to £50,000 per annum plus only 6% of revenues. As the table below shows (using estimated amounts because the advertising revenues generated by Classic FM are not published), Global Radio purchased Classic FM just at the time when its licence started to cost significantly less than in previous years.

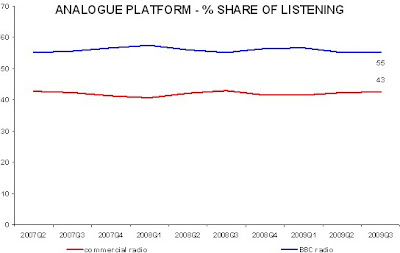

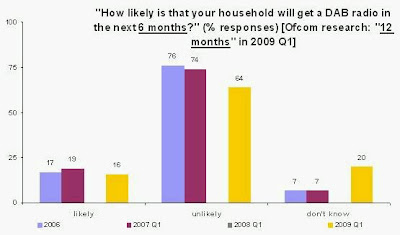

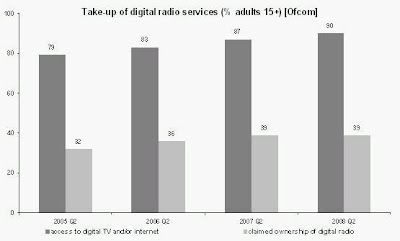

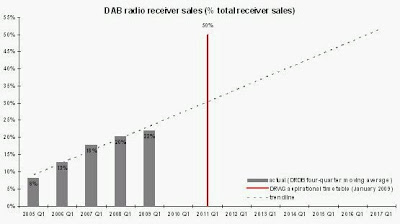

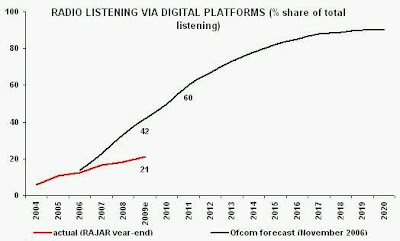

Why did Ofcom decide to reduce the cost of Classic FM’s licence so substantially? Because Ofcom believed that the analogue FM spectrum used by Classic FM would become less and less important with time, as listening via digital platforms, mostly DAB, rapidly replaced FM listening. Ofcom’s own forecast, made in November 2006, anticipated that digital platforms would account for 60% of all radio listening by 2011, the date when Classic FM’s licence expires. Quite how this justified a 95% cut in the licence fee, alongside a 57% cut in the revenue charge, was not explained by Ofcom. Essentially, Ofcom offered Classic FM’s owner the bargain analogue radio licence deal of a lifetime.

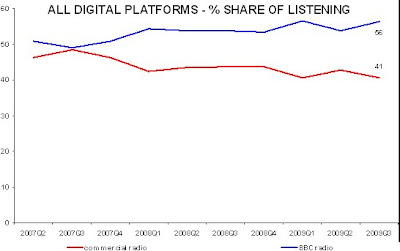

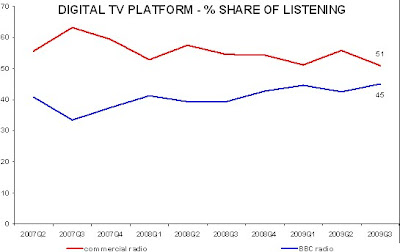

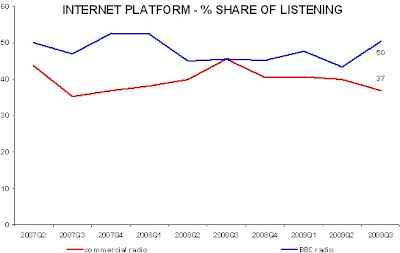

Ofcom’s forecast of digital radio listening turned out to be wildly over-optimistic, appearing to be based more on wishful thinking than on available evidence. Whilst Ofcom had forecast that digital platforms would account for 42% of radio listening by year-end 2009, industry data show the present outcome to be 21% for all radio and 20% for commercial radio. [RAJAR Q3 2009]

The inaccurate Ofcom forecast for consumer uptake of digital radio (never subsequently updated publicly) merely confirmed the belief within a large part of the radio industry that digital radio was about to exhibit exponential growth. This Ofcom forecast, accompanied by supporting comments from the regulator (for example, six months later, Ofcom director of radio Peter Davies said: “we are potentially at a Freeview moment with digital radio”), proved significant in misleading stakeholders into believing that the death of analogue radio was just around the corner. The regulator could not have got it more wrong.

Ofcom’s inability to forecast the radio market it regulated has resulted in a loss of millions of pounds of potential commercial radio licence fees for the Treasury, not only from Classic FM, but from the other two national commercial stations whose licence fees were also reduced. By Ofcom’s own estimate, under the previous formula the three stations combined had paid £7m per annum, but were now being charged less than £1.5m per annum. Over the four-year period until the three stations’ licences expire in 2011/2, the total revenue foregone to the Treasury will be around £22m. The Digital Britain proposal to extend these national radio licences for a further seven years, if the present licensing payment scheme is continued, would increase the total potential revenue lost to the Treasury to more than £50m.

Neither RAJAR nor Classic FM release data publicly showing the proportion of the station’s listening derived from digital platforms, but it presently seems unlikely that the station would voluntarily give up using FM for broadcasts after 2011 (when the present licence expires), and probably not even after 2018 (the revised expiry date if Digital Britain’s proposed seven-year licence extension were legislated). Effectively, the Digital Economy Bill would merely enable the largest player in the commercial radio sector not only to hang on to its ‘cash cow’, but to continue paying its present low licence payments to the Treasury for the FM radio spectrum it uses.

The losers from this arrangement are:

• taxpayers who, thanks to Ofcom’s poor forecasting, are now effectively subsidising the FM spectrum used by the commercial radio sector’s single most profitable asset

• the rest of the commercial radio sector who will never be able to match Classic FM’s operating margin because their own costs and revenues are considerably more constrained

• new entrants to the radio sector who wish to bid for the Classic FM licence when it expires in 2011 and are willing to pay a realistic, market price for the licence, but will be denied the opportunity by the government’s offer of an automatic licence renewal.

Politically, the proposals in the Digital Britain final report could not have isolated Classic FM as the sole commercial radio station to have its licence automatically renewed through new legislation. So the renewal proposal was extended not only to all three national commercial stations, but also to all local analogue stations that are broadcasting on the DAB platform. In July 2009, I suggested that this Digital Britain proposal was still iniquitous to the remaining local commercial stations that cannot or will not broadcast on DAB. It appears now that the Digital Economy Bill is likely to extend the proposed licence extension to all analogue commercial radio stations (whether or not they simulcast on DAB).

So every analogue commercial radio station will now be offered an automatic licence extension! Is that not a universal ‘good thing’? Well, no, because there is rarely a ‘free lunch’. Lord Carter was determined to extract a price from the entire commercial radio sector for bowing to persistent demands from Global Radio for new legislation to renew its Classic FM licence. The strings he attached are related to the government’s insistence that the whole radio industry use DAB as its main broadcast platform. This is why two entirely unrelated issues – Classic FM’s licence and DAB consumer uptake – have now become so intertwined in the proposed legislation.

In the seven-year renewal offered to every commercial radio licence, the government proposes to insert a clause that will allow it (via Ofcom) to terminate that licence extension with two years’ notice if the radio industry as a whole (commercial radio and the BBC) does not achieve these goals:

• 50% of radio listening to be via digital platforms by 2013

• DAB transmission infrastructure to be upgraded significantly.

It is a ‘carrot and stick’ approach: ‘We the government will give you all a free licence extension if you collectively promise to make DAB work. But, if we find you do not succeed in making DAB work, we will take your licences (and hence your businesses) away altogether’. The problem here is that the buck has been passed on to a wide and varied constituency of 300 commercial radio stations, many of whom have very little or no control over whether DAB can be turned into a successful delivery platform.

It is the entire commercial radio industry that will be expected to potentially pay the price with its own lives in exchange for changes to primary legislation that allow Global Radio to hang on to its ‘cash cow’ Classic FM licence. What seems even more unfair is that the entire DAB platform is owned and controlled by a mere handful of the largest UK commercial radio companies who, between them (and the BBC and transmission company Arqiva), wield the power to make DAB a success or failure.

If the largest commercial radio owner, Global Radio, had demonstrated incredible confidence in the DAB platform, maybe it might instil confidence in the rest of the radio sector that DAB could be made a consumer success by 2013. However, although Global Radio has regularly talked the DAB talk, it has hardly walked the DAB walk. Global had been the largest owner of commercial DAB infrastructure until, in April 2009, it sold its 63% stake in the national DAB multiplex and its wholly owned group of local DAB multiplexes. At the same time, it has sold or closed all but two of its digital-only radio stations, which exist now only as music jukeboxes.

Of course, for Global Radio, none of the DAB ‘strings’ really matter. It thinks it has got exactly what it wanted in the forthcoming Digital Economy Bill – to keep its valuable Classic FM licence. This is its significant short-term goal and may be the only thing that can keep the group afloat financially. Who knows? If the media ownership rules are relaxed, Global might be able to sell its entire radio business to Murdoch or RTL or MTG before the 2013 date of judgement on DAB is even reached.

For a while, many in the industry had seemingly been happy to line up behind Global Radio, uncertain of their own futures and relatively uninformed on these complex regulatory and legislative issues. But the truth is dawning on many – what is good for Global Radio is not necessarily good for the rest of the commercial radio industry. The future of commercial radio should remain in the collective hands of the industry itself, not be determined by one individual owner. And the issue of radio licence renewals should not have to be linked to the future performance of the DAB platform.

Digital Britain and the Digital Economy Bill offer a rare opportunity to update the regulatory regime for the entire commercial radio sector, rather than merely to offer one company a ‘phone a friend’ millionaire lifeline.

[For the purpose of transparency, I contributed sector analysis to two documents that were part of the Digital Britain process – a pre-consultation overview and the regulation of local radio.]

[Note to the table: the estimated costs of the Classic FM licence fee are simplified. Firstly, the cash amount paid increases annually from £1,000,000 in 1999 to £1,161,000 in 2006 and subsequently, in line with the Retail Price Index. The £50,000 cash payment will similarly be adjusted. Secondly, the revenue percentage paid is applied only to “advertising and sponsorship revenue attributable to national analogue listening hours”, but this data is not published, so 100% of estimated revenues have been assumed to derive from the FM platform.]