Did you hear about the inaugural Digital Radio Stakeholders Group meeting held on 1 November 2010 at the government’s DCMS [Department for Culture, Media & Sport] office? Probably not, unless you were one of the couple of dozen people who were in attendance. Otherwise, you were in the majority who were unaware of the event. There was no public pre-announcement of this meeting. Afterwards, there was only one article about it in the media trade press. Google returns ‘no results’ from an internet search for ‘Digital Radio Stakeholders Group’, even though this is the title writ across the top of the agenda circulated for the event.

You have to look in the new government’s Digital Radio Action Plan, published in July 2010, to discover:

You have to look in the new government’s Digital Radio Action Plan, published in July 2010, to discover:

“The Government will chair a Stakeholder Group which will be open to a wide range on industry and related stakeholders. The principle purpose of this Group will be to inform external stakeholders of progress against the Action Plan and gather views on emerging findings. We expect that the Group will meet quarterly.”

The government’s project management plan anticipated that, by Q2 2010, it would be able to:

“secure commitment from the Government Digital Radio Group and the Stakeholders Groups to the Action Plan.” [Task 5.1]

This pre-determined outcome was justified on the grounds that:

“Successful implementation of the Digital Radio Switchover programme will only be achieved through close Government-Industry co-operation. […] This will include commissioning and delivery of reports, reviewing progress against key milestones and disseminating information to key stakeholders.”

So, essentially, the Digital Radio Stakeholders Group seems to be an almost non-existent forum that has only been convened to secure some kind of external ‘rubber stamp’ for the government’s proposals on DAB radio. It will allow the government, when challenged as to the democratic basis of its DAB radio policy, to assert confidently: “We convened a stakeholders group and it endorsed our proposals.”

This is cynical government at its worst. A ‘faux consultation’ that pretends to have asked a group of somebodies to endorse a government policy for which no mandate has ever been given by the electorate. It is similar to the manipulation practised by Ofcom in its radio policymaking (viz. Ofcom’s recent decision to permit Smooth Radio to dump its commitment to broadcast 45 hours per week of jazz music, after having acknowledged that 13 of the 15 responses submitted to its public consultation were opposed to this loss of jazz).

According to a government document, the Terms of Reference for the Digital Radio Stakeholders Group are as follows:

“Purpose

To enable a wide range of organisations to contribute to the process of delivering the Digital Radio Action Plan

Objectives

• To inform all stakeholders of progress with the Action Plan

• To seek the views of stakeholders on future progress of the Action Plan

• To provide an opportunity for all stakeholders to share news, views and concerns relevant to the Digital Radio Action Plan

Membership

Any organisation with a valid interest in the objectives of the Digital Radio Action Plan may be a member. Members will include consumer representative bodies, broadcasters, manufacturers, retailers, vehicle manufacturers, transmission network operators, content providers. The Group will be chaired by BIS in the first instance, though in principle the Chair could be any person acceptable to the majority of stakeholders and able to represent the collective views of the stakeholders to the Steering Board.

Mode of operation

The Digital Radio Stakeholders Group will meet quarterly.

The Chair will report the views of the stakeholders, as expressed through the meetings of the Stakeholders Group, to the Steering Board.”

So what happened at the first meeting? Very little, according to some of those who were present. It was a game of two halves. In the first half, the bureaucrats put their case. From the government, Jane Humphreys, head of digital broadcasting & content policy, BIS [Department for Business Innovation & Skills]; John Mottram, head of radio & media markets, DCMS; and Jonny Martin, digital radio programme director, BIS/DCMS. From Digital Radio UK, Ford Ennals, chief executive; Jane Ostler, communications director; and Laurence Harrison, technology & market development director. Then, in the second half, representatives from Age UK, the Consumer Expert Group, Voice of the Listener & Viewer and W4B raised issues on behalf of the consumer.

At the end of it, I guess the government-appointed chairman could return to her government office, tick the box on the government wall planner that says ‘stakeholder commitment’ and be pleased that this ‘rubber stamp’ had cost the taxpayer only an afternoon’s salary plus some tea and biscuits for the ‘stakeholders’. Well worth it!

More interesting than noting those who attended is identifying who was not there:

· No presentation by Ofcom, whose longstanding ‘Future of Radio’ policy has forced the DAB platform upon the public for almost the last decade

· Nobody from the largest commercial radio owners – Global Radio, Bauer Radio and Guardian Media Group – that have considerable investments in DAB multiplex licences

After the meeting, under the headline ‘RadioCentre quits digital radio meeting’, Campaign reported:

“RadioCentre, the commercial radio trade body, has walked out of discussions over the future of digital radio after the BBC licence-fee settlement did not commit BBC funds to roll out DAB radio. The body refused to attend a [Digital Radio Stakeholders] meeting on 1 November after the [BBC Licence Fee] settlement, published last week, included provision only for [BBC] national DAB [upgrade].” [I noted this development in a blog last month]

Whatever RadioCentre’s reason for non-attendance (and the story in Campaign has not been refuted), this kind of stance is a disgrace. Raising two fingers to the people you are supposed to be persuading of your DAB policy is not a clever PR strategy for the commercial radio industry. But I am not surprised. All the organisations pushing for DAB radio have increasingly adopted a ‘bunker’ mentality that precludes any direct contact with the public. What we appear to have now is:

· Ofcom refusing to engage in public discussion about its DAB ‘Future of Radio’ policy

· The government organising a Stakeholder Group to rubber stamp its unrealistic, dictatorial policy on DAB radio

· Digital Radio UK refusing to engage in public explanation of its DAB campaign work, as illustrated by its non-existent web site

· RadioCentre and its members now refusing to attend a meeting to explain just how/why DAB is still being pursued

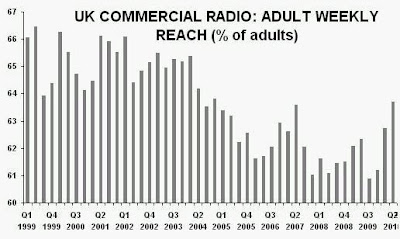

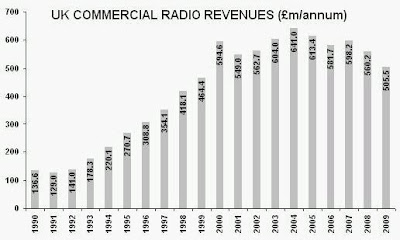

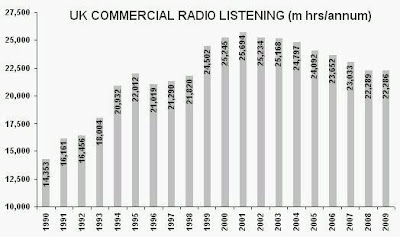

At the same time, the public – the consumers, the 46,762,000 adults who spend 22.6 hours per week listening to radio – have been omitted altogether from these manoeuvrings that are still focused upon trying desperately to force them to purchase DAB radio receivers. The public had been omitted from the proposals at the very beginning of DAB more than a decade ago, which is precisely why it failed, and they are still being omitted today.

This is not the first time that government ‘stakeholder’ meetings about DAB radio have been organised simply to tick a box. As part of the previous government’s attempts to solve the DAB problem, in 2008 it convened a Digital Radio Working Group with two similar ‘stakeholder meetings’ held at DCMS. I attended and felt they existed purely for the bureaucrats to report back to their superiors that they had done something to ‘disseminate’ their policies. DCMS’ own write-up of the first meeting recounted bluntly:

“A stakeholders meeting was held on 10 March and offered opportunities for a wide range of views to be heard.”

A place where “views” were merely “heard”. The ineffectiveness of these earlier stakeholder meetings is demonstrated by re-visiting the agenda for the first of them. The issues tabled for discussion nearly three years ago (“How to make digital radio the predominant platform for listening to radio in the UK? What are the barriers to this? How can these barriers be overcome?”) still remained the same at this month’s meeting. Worse, none of the DAB technical problems identified then have been solved in the interim. And guess what? All trace of these 2008 meetings ever having happened has been erased from the DCMS website (in 2008, I had had to write to DCMS to get them to add the meeting details to their website).

The next meeting of the Digital Radio Stakeholders Group will be held on 3 February 2011 at DCMS/BSI, 1 Victoria Street, London SW1H 0ET. If you belong to any kind of community group or organisation (even if it is your neighbourhood watch) whose members are likely to be impacted by the government’s policy on digital radio switchover, I suggest you write to Jane Humphreys (e-mail to [first name][dot][second name]@bis.gsi.gov.uk) and ask for an invitation to this next meeting.

‘Stakeholder’ radio listeners should turn up to the February meeting and shout: “I’m mad as hell and I’m not going to take this any more!” … or maybe the DAB plug will already have been pulled by then.