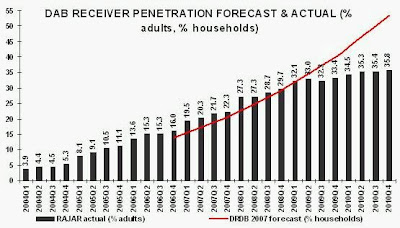

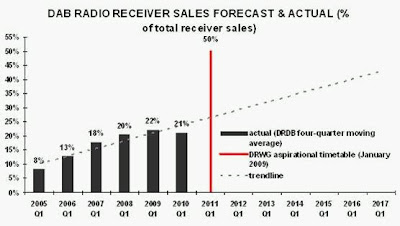

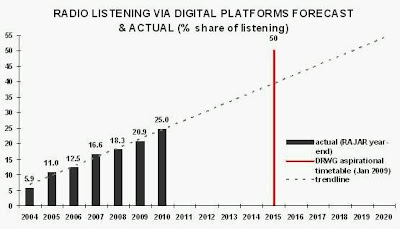

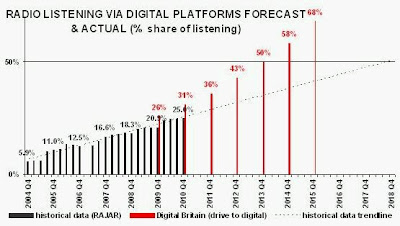

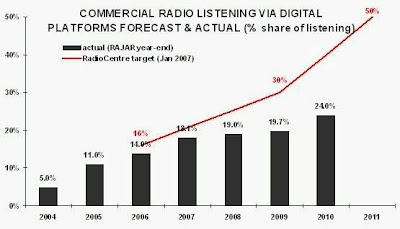

Some of Digital Britain’s radio recommendations were unworkable. However, the notion has remained that FM and AM analogue transmitters of the UK’s national radio stations will be switched off once digital radio listening passes the 50% threshold. This was never practical. It was a ‘threat’ propagated by government to the public in the hope of forcing them into buying more DAB radios, instilling fear that they would otherwise lose their favourite stations. The threat failed.

The problem with any threat is that, once it has failed, it remains difficult for the protagonist to climb down. So the threat continues to be propagated. For what reason now? So as not to make those who issued the threat look completely foolish. The need to save face has locked the government apparatus into a fiction that BBC and commercial radio will willingly throw away half their audiences by closing their FM/AM transmitters. This was never true.

THE BBC

‘Universal’ reception of the BBC’s core public services is mandatory. It would prove impossible to levy the BBC Licence Fee on every UK household if (almost) the entire population could not receive the BBC services for which they pay.

The BBC Charter & Agreement requires:

“12. Making the UK Public Services widely available

(1) The BBC must do all that is reasonably practicable to ensure that viewers, listeners and other users (as the case may be) are able to access the UK Public Services that are intended for them, or elements of their content, in a range of convenient and cost effective ways which are available or might become available in the future.”

Would the BBC switch off analogue transmissions of its national networks once more than 50% of listening was attributed to digital platforms? Of course not. You would be a complete fool to slash your radio audience by half, particularly as such an action would contradict the BBC Charter & Agreement.

Could the government insist that the BBC switched off the analogue transmissions of its national networks? Only if it wanted a revolution on its hands. It would be difficult to think of a policy more likely to lose it the next General Election.

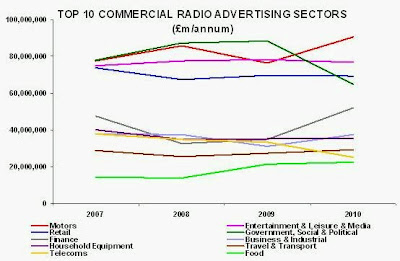

COMMERCIAL RADIO

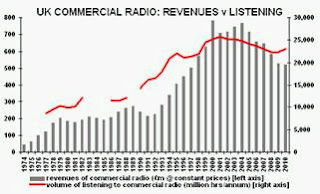

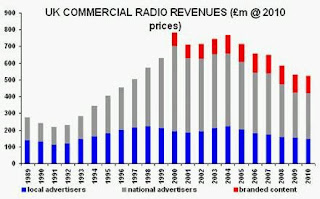

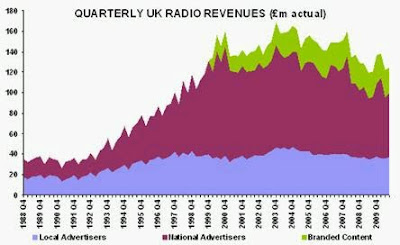

The revenues of commercial radio are directly related to the sector’s volume of listening. If commercial radio switched off its analogue transmitters once digital listening had passed the 50% threshold, at a stroke it would risk losing 50% of its volume of listening and, subsequently, 50% of its revenues. Would it do that? No, of course not.

RadioCentre’s self-interested ‘policy’ has been to argue that the BBC national networks should turn off their analogue transmitters first, years in advance of commercial radio stations. Radio Chicken, anyone? Naturally, RadioCentre failed to mention that the outcome of this proposal would be likely to significantly increase its member commercial radio stations’ analogue audiences and revenues. There is nothing quite like trying to persuade your competitor to commit joint suicide … first.

Additionally, the value of commercial radio companies is vested in the scarcity of their analogue FM/AM licences. Because no new analogue licences are awarded by the regulator, each existing licence has a significant intrinsic value, even if the business using it is not profitable. The same is not true of DAB licences. Anybody can apply to Ofcom for a DAB licence by filling in a form and paying a relatively small fee.

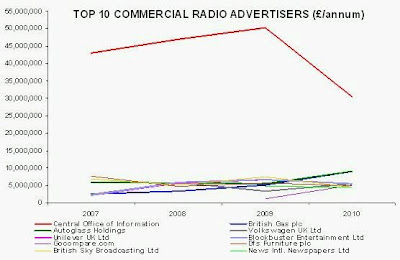

An example of the value of analogue licences to commercial radio owners is Absolute Radio. In 2008, Times of India paid £53.2m for Virgin Radio, comprising one national AM licence and one London FM licence. Having re-launched the station as Absolute Radio, the company lost £4.3m in 2009, but its balance sheet still retains considerable value because of the scarcity of its two analogue radio licences. If Absolute Radio were put up for sale, someone would be interested in buying it because of that scarcity.

By contrast, when DAB commercial radio services such as Zee Radio, Islam Radio, Muslim Radio, Flaunt and Eurolatina no longer wanted their digital radio licences in 2010, there was no queue of potential buyers. They simply handed their licences back to Ofcom because those licences were not scarce.

This is why it would prove financially suicidal for commercial radio to switch off its FM/AM transmitters. It would have to write down the value of those scarce analogue licences to zero in its balance sheets which, at a stroke, would negate almost the entire value of the licence owners. Not a good company strategy.

So, when headlines such as ‘Absolute Radio mulls AM switch-off’ appear in the trade press, they should be read with a bucket of salt. The headline might as well say: ’Absolute Radio mulls destruction of shareholder value.’

And, when yet another DAB proponent appears on radio or television to persuade you, in all seriousness, that the UK’s most listened to national radio services – both BBC and commercial – will imminently be switching off their AM/FM transmitters, please feel justified to laugh in their face.

This is about as likely to happen as Tesco putting security guards at their store entrances to tell the public to shop elsewhere because they want fewer customers.

FOOTNOTE:

It emerged last week that, after the Norwegian state classical music station ‘Alltid Klassisk’ abandoned FM transmission on 1 July 2009 for DAB transmission, its audience contracted from 25,000 to 10,000 per day.

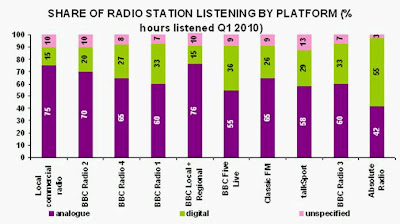

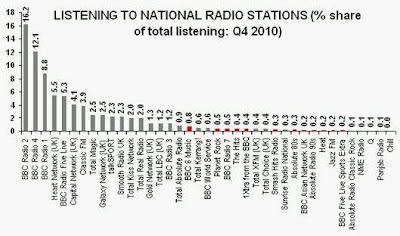

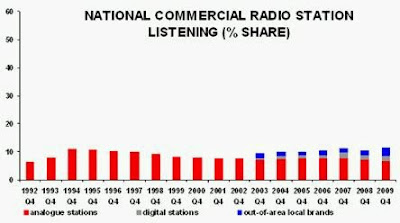

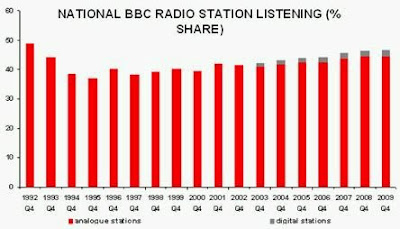

Now, consider that only 20% of listening to BBC Radio 2 is via digital platforms (in Q1 2010), lower than the 24% average for all stations [see Sep 2010 blog]. If that average ever managed to reach the 50% threshold, it might leave 60% of Radio 2’s audience still listening via analogue. That’s 8m listeners that Radio 2 would have to turn its back on as a result of FM switch-off. Time for the BBC to start erecting barricades outside Broadcasting House.

[thanks to Eivind Engberg]