The closure of Edinburgh station Talk 107 on 23 December almost coincided with the fifth birthday of Ofcom (on 29 December). Talk 107 was the first commercial radio station to be licensed by Ofcom, so its failure and subsequent closure could seem symptomatic of Ofcom’s radio licensing strategy. Over five years, instead of Ofcom playing a significant role in creating a vibrant, profitable and creative UK commercial radio industry, its licensing decisions have often exacerbated the problems of a sector already beset with massive structural and financial challenges.

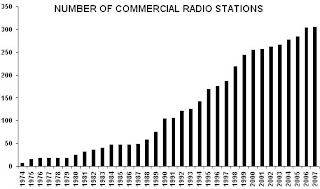

Ofcom has licensed 39 new commercial radio stations to date, taking the total number of UK licensed commercial radio stations past the 300 mark. This number, in itself, is a large part of the problem. These newly licensed stations each add a whole new set of largely fixed costs to the sector. Even if the average cost of each of these new stations is only £250,000 per annum, Ofcom’s licensing has increased sector costs by almost £10m per annum (in 2007, Ofcom estimated the sector’s aggregate costs as £400m).

Ofcom has licensed 39 new commercial radio stations to date, taking the total number of UK licensed commercial radio stations past the 300 mark. This number, in itself, is a large part of the problem. These newly licensed stations each add a whole new set of largely fixed costs to the sector. Even if the average cost of each of these new stations is only £250,000 per annum, Ofcom’s licensing has increased sector costs by almost £10m per annum (in 2007, Ofcom estimated the sector’s aggregate costs as £400m).

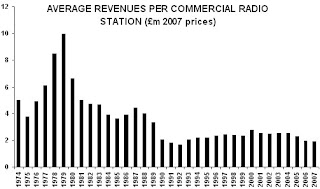

At the same time, most newly launched commercial radio stations have failed to attract significant new listening or new revenues to the sector. New stations seem to simply cannibalise the audiences of existing commercial radio stations (I researched the impact of introducing the tier of regional commercial stations and found only one station had not cannibalised commercial radio audiences). As a result, the sector’s aggregate costs have increased whilst its aggregate revenues have not been expanded, and so profit margins are being squeezed further.

At the same time, most newly launched commercial radio stations have failed to attract significant new listening or new revenues to the sector. New stations seem to simply cannibalise the audiences of existing commercial radio stations (I researched the impact of introducing the tier of regional commercial stations and found only one station had not cannibalised commercial radio audiences). As a result, the sector’s aggregate costs have increased whilst its aggregate revenues have not been expanded, and so profit margins are being squeezed further.

Additionally, the formats of many of the winners in Ofcom’s licensing ‘beauty parade’ were inevitably destined for commercial failure, with Ofcom seeming to ignore the empirical evidence. In a market the size of Edinburgh, Talk 107’s talk format could never succeed, given that the same format has been unable to make an operating profit in the UK’s largest local market, London, since the end of the 1980s. Similarly, Ofcom’s idea of introducing a local rock music station in Plymouth would have been a disaster (the station never even launched) given the miserable audiences for Xfm and Virgin Radio. And the three Original stations licensed by Ofcom launched with such esoteric music formats that their failure quickly prompted owner CanWest Global to sell up and quit the UK radio business altogether.

The size of most of the newly licensed stations was insufficient to ever make them profitable. Ofcom’s own research found that the majority of small stations fail to generate an operating profit – stations serving under 50,000 adults make an average annual loss of £3,000; stations serving between 50,000 and 150,000 adults make an average annual loss of £20,000; and stations serving between 150,000 and 250,000 adults make an average annual profit of £65,000. Although 63% of commercial radio stations serve areas of less than 250,000 adults, they collectively generate only 11% of sector revenues.

Knowing the unprofitable economic performance of most small commercial radio stations, it made no commercial sense for Ofcom to choose to licence 21 of its 39 new stations to populations of 250,000 or less. All this has done is increased the number of loss-making commercial radio stations and dragged down the profitability of the entire sector. The roll-call of stations licensed by Ofcom in its first five years includes:

- Talk 107 Edinburgh, closed by UTV after 15 months on-air

- Touch FM Banbury, up for sale or closure by CN Group after two years on-air

- Brunel FM Swindon, sold by The Local Radio Company after 21 months on-air to Laser Broadcasting, forced into administration four months later, acquired by Southwest Radio

- Original Solent, Original Bristol and Original Aberdeen, sold by Canwest Global which exited its UK radio venture two years after Solent had launched

- Diamond FM Plymouth, never launched by Macquarie Bank

- Southend Radio Southend, sold by Tindle Radio to Adventure Radio before it launched

- Sunshine FM Monmouth, acquired by Murfin Music when Laser Broadcasting forced into administration after 10 months on-air

- Xfm South Wales sold by GCap Media to Town & Country after six months on-air

- Minster FM Northallerton, licensed to serve 39,000 adults, annexed to Darlington after eight months on-air

- Perth FM Perth, eventually launched last month, two years after winning its licence from Ofcom, and ten weeks after owner Mark Page closed L107 Lanarkshire

- The Severn Shrewsbury and The Wyre Kidderminster, now sharing programmes under co-owner Midland News Association

- kmfm Ashford, now sharing programmes with co-owned KM Radio stations

- [a question remains over the control of Andover Sound Andover and whether licence winner Tindle Radio has sold or reduced its 100% stake between the licence award in July 2006 and the station’s launch in May 2008]

Some of the 39 new local stations licensed by Ofcom are only required to broadcast locally-produced content for four hours per day on weekdays (the breakfast show), while the majority are required to broadcast no more than four hours per day of locally-produced content on weekends.

The question has to be asked…. Are the financial losses incurred by these stations worth the marginal amounts of local content offered to the populations in the markets they serve, and the resultant low ratings achieved by most of them?

So what is the point of licensing small local radio stations that barely broadcast local content and are unlikely to break even?