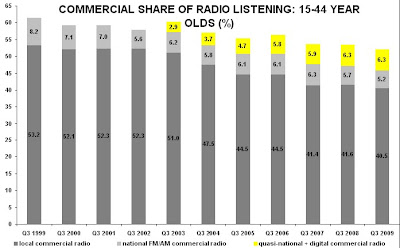

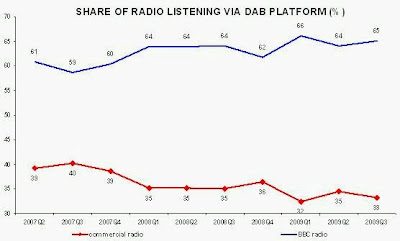

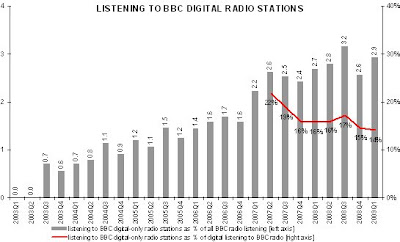

The latest RAJAR radio audience data demonstrated one thing clearly: the UK radio industry’s strategy for its digital stations is in tatters. Audiences for digital radio fell off a cliff during the last quarter of 2009. This did not appear to be the result of any specific strategy shift (no station closures, only one minor format change) but more the result of increasing public malaise about the whole DAB platform and the radio content that is presently being offered on it (plus a little Q4 seasonality) . The figures speak for themselves.

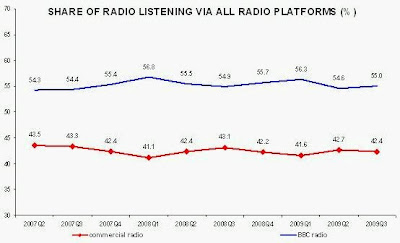

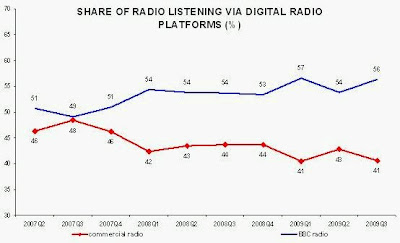

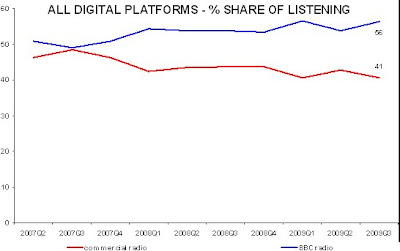

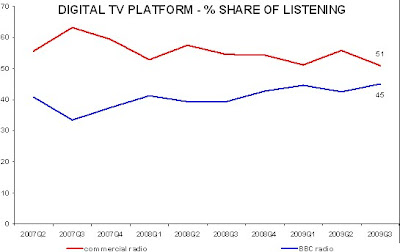

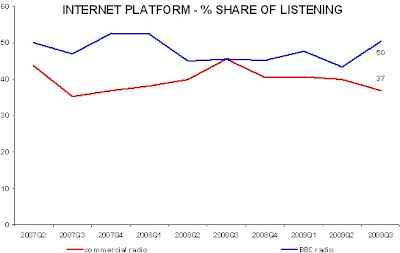

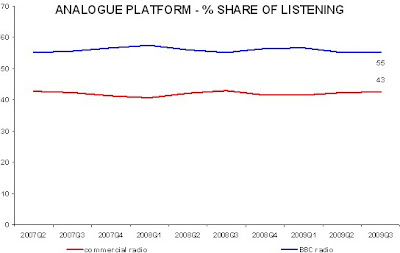

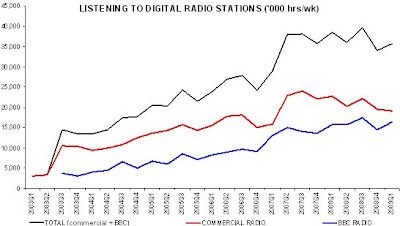

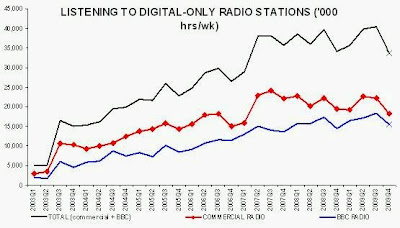

Total listening to digital radio stations is back down to the level it achieved in 2007, following a period of sustained growth between 2000 and 2007. Far from moving towards some kind of exponential growth spurt as the industry had expected, total listening now seems to have plateau-ed. It appears that market saturation has already been reached for much of the content presently available on digital radio platforms, considerably earlier than had been anticipated, and at a level of listening that cannot justify these stations’ existences for their commercial or BBC owners.

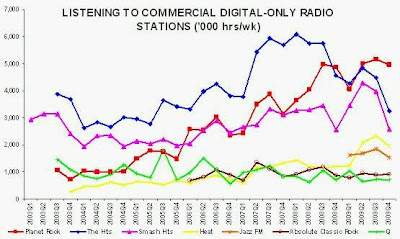

In the commercial sector, only Planet Rock has maintained its momentum, probably a reflection of its commitment to offering its listeners genuinely unique content. Elsewhere, the jukebox music stations have suffered massive falls in listening, possibly a result of their ease of substitution by online offerings such as Spotify and Last.fm, and of owner Bauer’s policy to curb investment in digital radio broadcast platforms and content.

Commercial radio has talked the digital talk for years about striving to make DAB a successful platform, vaguely promising new digital radio ‘content’ that it has still not delivered. Instead, it has spent the last few years cutting costs, consolidating, lobbying the government, complaining about the BBC, closing its digital stations and contracting out its DAB capacity to marginalised broadcasters (religious, ethnic, government-funded and listener-supported stations) that will never attract mainstream audiences to the platform (and whose listening is not even measured in the RAJAR audience survey).

From the listener’s perspective, the only thing that has happened to the DAB platform in recent years is the disappearance of commercial digital stations such as OneWord, TheJazz, Core, Capital Life and Virgin Radio Groove. For the average consumer, the arrival of Traffic Radio, Premier Christian Radio or British Forces Broadcasting Service are hardly replacements.

A report commissioned by RadioCentre from Ingenious Consulting in January 2009 concluded:

“Commercial radio is now at a crossroads with respect to DAB. It needs either to accept that the commercial challenges of DAB are insuperable and retreat from it – such a retreat, because of contractual and regulatory commitments, would be slow and painful; or strongly drive to digital.”

In the year since this report was prepared, commercial radio has done neither. Instead, it has spent a small fortune on parliamentary lobbying, not one iota of which has had a direct impact on 10 million increasingly baffled DAB radio receiver owners. These latest RAJAR data convey their clear message that content is their only concern.

For the BBC, the problem is somewhat similar. With the exception of Radio 7, listening to its digital radio stations remains unimpressive, despite them benefiting from massive BBC cross-promotion over many years. Some stations are outright disasters – Asian Network is listened to less now than it was almost seven years ago, when only 158,000 DAB radios had been sold. Some stations are simply not suited to the DAB platform – 1Xtra targets a youth audience who listen to a lot of radio online and via digital TV, but who have little interest in DAB (particularly as DAB is not available in mobile phones). Some stations will become redundant in an increasingly on-demand world – Radio 7 would eventually be little more than a shopfront for the huge pick’n’mix BBC radio archive to be made available to consumers online.

For the BBC, it is becoming increasingly hard to justify spending, for example, £12.1m per annum on the Asian Network when its peak audience nationally is only 31,000 adults. Broadcast platforms such as FM attract huge audiences for a fixed cost, making them the most efficient distribution system for mass market live content. As a result, Radio 1 costs us only 0.6p per listener hour. By comparison, the Asian Network is costing 6.9p per listener hour, probably making it more expensive to ‘broadcast’ than to send each listener a weekly e-mail attaching the five hours of Asian Network shows they enjoy.

The BBC should still be congratulated for creating new digital radio services in 2002 that attempted to fill very specific gaps in the market which commercial radio was unlikely to ever find commercially attractive. This is precisely why we value a public broadcaster in the UK. However, the BBC digital radio strategy over the last decade has suffered from:

• The BBC’s evident inability to successfully execute the launch of genuinely creative, innovative radio channels that connect with listeners (GLR, the ‘new’ Radio 1, the original Radio 5)

• The BBC pre-occupation with constantly creating new ‘broadcast channels’ when most niche content is more suited to narrowcasting and delivery to its audience via IP (live, on-demand or downloaded).

For the UK radio industry, its digital ‘moment of truth’ has belatedly arrived. A new strategy now has to be adopted which does not continue to raise the DAB platform to the level of a ‘god’ that has to be worshipped above all others. The future of radio is inevitably multiple-platform and the industry’s focus has to be returned to producing content, rather than trying to control the platforms on which that content is carried.

I suspect that Tim Davie, director of BBC Audio & Music, will eventually lead these winds of change, following in the wake of director general Mark Thompson’s pronouncements at the end of this month as to where the internal financial axe will fall. Where the BBC leads, commercial radio will inevitably (have to) follow.

The future digital radio strategy is likely to be ‘horses for courses’. Rather than all radio content being delivered via all available platforms, it will in future be delivered only where, how and when it is most demanded by listeners. Our economic times make this mandatory. The DAB platform’s mass market failure will make it necessary.