In 1998, the Radio Authority advertised a licence for the “first and only national commercial digital [DAB] multiplex licence.” There was no stampede of applicants. By June 1998, the regulator had to issue a press release with the headline “Radio Authority receives one application ….” The sole applicant was ‘Digital One’, 57% of which was owned by commercial radio’s GWR Group plc, whose chief executive Ralph Bernard later admitted:

“GWR was encouraged to apply for the national [DAB multiplex] licence and was under some pressure to invest in the opportunities for a national licence from the then regulator. Had we not done it, there would be no national DAB platform now. Not only that, [the regulator] did not know what they would have done on the question of national radio stations with regard to the opportunities given by the then government to renew their national licences for a further period of time if they were to commit to going digital. But how can you [do that] if there are no opportunities to go digital because there is no national multiplex? When I put that question to the Radio Authority, I was told that the answer was: ‘We don’t know what would happen – there is no Plan B’. It was just an assumption that someone would go for [the national multiplex].”

Bernard had a hard time convincing his own board that the DAB licence was a worthwhile investment for a radio group that, until then, had owned radio stations rather than transmission infrastructure:

“When we were seduced into believing that this was going to be the only [national DAB] licence, we realised that there would be substantial losses, but the payback would be when you have the opportunity to be the only player in the national market for DAB. When it’s the Radio Authority, an agency of government, you tend to believe what you are told. On that basis, the investment was justified and, at the time, getting it through my Board was not easy. Persuading shareholders, particularly the larger ones, was not easy.”

Now, twelve years later, GWR Group no longer exists, Ralph Bernard is out of the commercial radio business, but the ‘Digital One’ national DAB platform is still there. Nobody really wanted it in 1998, and nobody really seems to want it now. Its ownership has changed hands like pass-the-parcel, GWR Group plc having merged into GCap Media plc, which was then sold to Global Radio which, in 2009, sold its majority stake in Digital One to transmission provider Arqiva. How many millions were thrown at Digital One over the years by GWR, GCap and Global Radio will probably never be known.

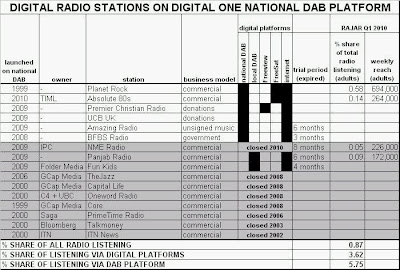

The only thing cheap about Digital One was the cost of its initial 12-year licence, a mere £10,000 per annum paid to the regulator for the radio spectrum it uses. The business model was that Digital One would lease space on the DAB platform to radio stations that would pay it rent (about £1m per year, dependent upon audio quality). Since opening for business in 1999, many digital-only stations have tried using the platform but, to date, almost none have stuck around. No digital radio station has yet made a profit.

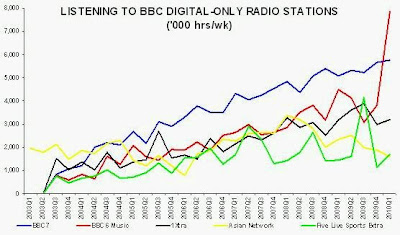

The latest additions to the lengthening list of stations that have failed to make the national DAB platform work for them are NME Radio and Panjab Radio, both of which quit Digital One in June 2010 (see shaded area of table). The reason? Almost no one was listening. Add together the digital-only stations broadcasting on the platform last quarter (and that are measured by RAJAR) and, in total, they accounted for less than 1% of total radio listening.

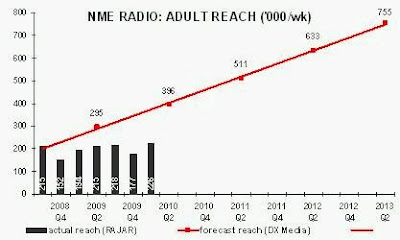

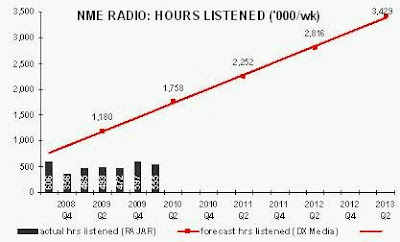

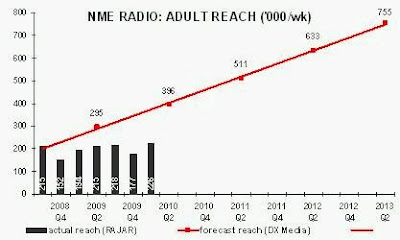

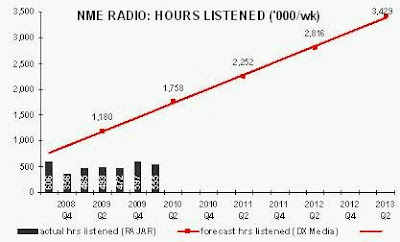

Yet the radio industry, the receiver manufacturers and their lobby groups are still spending money on campaigns to convince the public that DAB radio is a raging success. Digital One says its radio platform reaches “more than 90%” of the [UK] population,” equivalent to 46m adults. RAJAR tells us that 35% of those adults have a DAB radio. Yet only 226,000 adults per week listened to NME Radio, after nearly two years on-air. If you were in any way persuaded to believe the hype surrounding DAB, your business plan to start a digital radio station might look dangerously over-optimistic.

When NME Radio launched in June 2008, it had forecast that its audience would reach 396,000 adults per week by its second year. For most of its life, the station was broadcast on local DAB multiplexes (and online). Then, from 21 December 2009, NME Radio was made available nationally on DAB for an eight-month trial. Broadcasting to a much bigger potential audience, there should have been a positive uplift to the station’s performance in Q1 2010. However, there was no noticeable impact upon adult reach (226,000) or hours listened.

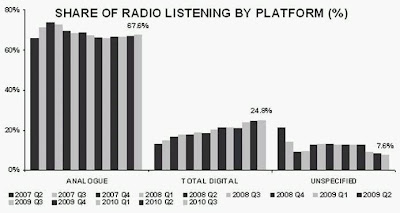

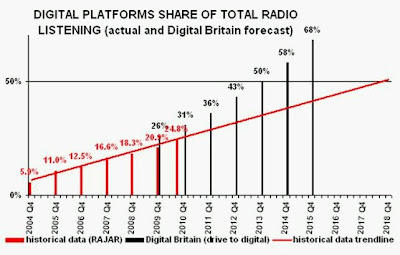

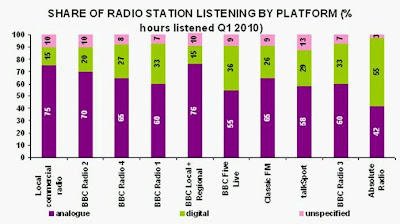

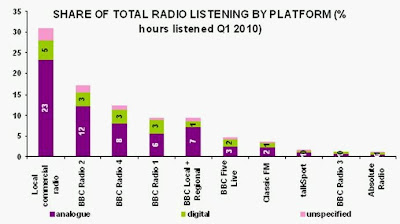

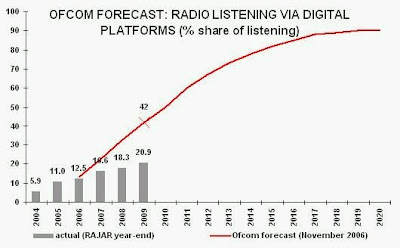

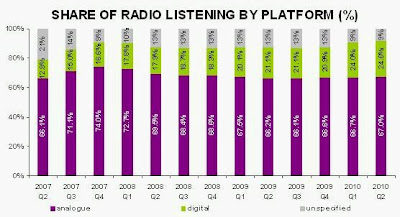

In its forecasts, NME Radio had projected that DAB would be “53%” by 2010. Maybe this referred to Ofcom’s forecast that, by year-end 2010, digital platforms (not DAB alone) would account for 50% of all radio listening. In fact, in Q1 2010, only 15% of listening to all radio was via DAB, and 24% was via all digital platforms (worse for commercial radio at 12% and 23% respectively). Ofcom’s forecast of how digital radio usage would grow was disastrously inaccurate. NME Radio did not stand a chance of commercial success using DAB.

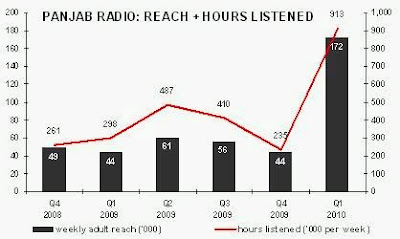

The other digital radio station that quit the national DAB platform in June 2010 was Panjab Radio. Like NME Radio, it had broadcast via local DAB multiplexes (and online), but was then made available nationally on DAB for a six-month trial from 1 December 2009.

There was no lift to Panjab Radio’s audience in Q4 2009, but the following quarter saw a noticeable increase to 172,000 adult reach and 913,000 hours listened per week. This was almost twice the amount of listening that NME Radio recorded on the national DAB platform, a real achievement for an ethnic radio station.

The day Panjab Radio had joined the national DAB platform, Digital One operations director Glyn Jones said:

“Like Premier Christian Radio and UCB UK, Panjab Radio relied on a fund-raising appeal to pay for the launch of the station. It’s interesting to see the growth of listener-supported stations, and the way they’re extending the range and choice of stations on air via digital radio. These are stations that neither a traditional commercial model nor the BBC have chosen to provide, but which listeners value so much that they’re prepared to help pay for them out of their own pockets.”

The sub-text was that the Digital One national DAB platform cannot support a commercial digital-only radio station because the financial returns are simply insufficient to cover the expense for it to lease space on the platform. If Panjab Radio had managed to sell advertising at the average commercial radio sector rate, it should have generated £1m per annum of revenue. However, an industry study in 2009 found that the average digital radio station generated only £130,000 revenue per annum (and Panjab Radio attracted less listening than others).

When Panjab Radio quit the national DAB platform in June 2010, Digital One’s Glyn Jones issued a press release that seemed over-eager to deflect the blame:

“Panjab Radio’s revenues come from a mix of traditional radio advertising plus fund raising among Britain’s Panjabi and Sikh communities. Following a strategic and financial review the station opted to end its national transmissions but to continue to broadcast on DAB digital radio in three parts of the country with significant concentrations of the target audience – the West Midlands, West Yorkshire and London.”

As the table above demonstrates, the national DAB platform’s history is littered with commercial digital radio stations that failed to make it work for them. Most of the stations currently on the national DAB platform are non-commercial and so do not need to meet their costs from advertising revenues. But religious stations, army radio and unsigned artists do not come close to the mass market purpose for which the platform was originally envisaged. Did GWR Group make its substantial investment in national DAB in the expectation that, after a decade, the platform would be filled with subsidised radio stations attracting tiny audiences?

Two years ago, I had written:

“This sudden flowering of ethnic, religious and publicly-funded radio stations on the DAB platform echoes the fate of the ‘AM’ waveband in the 1990s … The ‘DAB’ platform of 2008, particularly in London, is already starting to resemble the ‘AM’ platform of 1998, suggesting that ‘DAB’ might have already been written off by the sector as a means to reach the ‘mass market’ audiences that national advertisers desire from the medium.”

Since then, this desperate filling of DAB multiplex capacity with non-commercial stations has spread from London to the national platform. Bizarrely, given the overwhelming empirical evidence that this “first and only national commercial” DAB platform is not working, even after a decade of operation, Ofcom is keen to create a second quasi-national DAB platform. Its rationale is that:

“This could help to facilitate the creation of national commercial radio stations to create a consumer proposition analogous to that of Freeview: a wide range of popular and niche services, delivered digitally” because “we believe DAB still offers the best solution for the future growth of radio in the UK.”

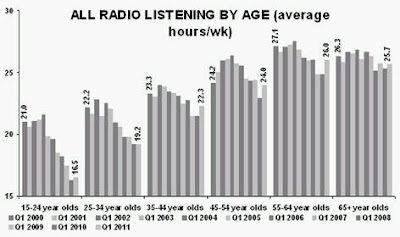

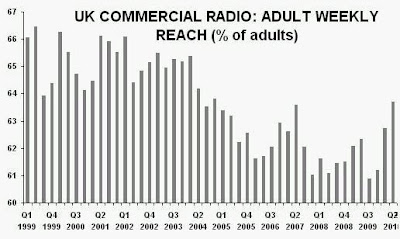

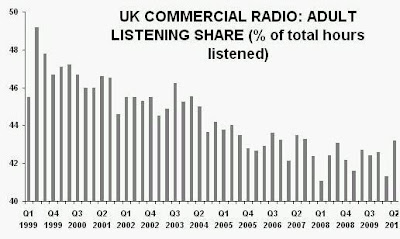

This nonsense was written in an Ofcom report less than a year ago, when the writing on the wall could not have been larger that the national DAB platform’s future for commercial radio was doomed. Surely, a regulator that refuses to deal with the reality of the here and now could be a regulator that will eventually find it has no future. For years, Ofcom (and its predecessor) have led the commercial radio sector a merry dance down a DAB blind alley that has proven almost fatal to the industry’s economic health.

If Ofcom publishes one more policy document proclaiming (as if it were still 1998) that ‘the future of radio’ is DAB, rather than it working to bang industry heads together to find a practical route out of the present mess, all it will succeed in doing is writing its own epitaph.