A posh voice opens doors. Not literally, unless you are royalty, but figuratively. Opportunities seem to fall out of the sky for those who speak in a recognised way that conveys their breeding and their assumed elevated status in British society. I have observed this as someone who has never considered myself posh, as someone who has never been perceived as posh, but as someone who was thrust unprepared into a world of posh people from the age of eleven. Until my first day at grammar school, I had mistakenly believed that ‘people were people’ (to quote Lou Rawls) and that ‘meritocracy’ was a fact rather than a fancy theory. My mum had believed it too, having just bought me a red ‘Harvard’ sweatshirt from Farnborough outdoor market for having passed the eleven-plus exam. I wore it to bed (in the style of Susan Saint James) for the next thirty years until it literally wore out .. but Harvard remained a fantasy.

My claim to have never had a posh, or posh-ish, voice could be challenged by someone who knew me at age four. I was shocked when I revisited a recording of my recital by heart at that age of ‘Winnie The Pooh’, made on a Uher reel-to-reel tape recorder my father had bought second-hand from the pages of ‘Exchange & Mart’ magazine which he would pore over every week. I sounded frighteningly like a distant relative of the Queen and nothing at all like my parents. Maybe I was trying to emulate fellow toddlers at Gay Trees nursery school on Grand Avenue where owner Mrs Potten had insisted I play a reluctant shepherd in the annual Nativity play. In summer, she would lead us all onto the adjacent Recreation Ground to sit on the grass and watch the uncensored violence of her one-woman Punch & Judy show.

During the following seven years, I attended a state school on a council estate where my posh-ish voice must have been modified by a desire to integrate with my new set of peers whose ‘overspill’ families had been relocated there from South London suburbs bombed during the War. From then onwards, the only posh voice evident in our household was my mother habitually answering our phone with “Camberley double one three one”, inexplicably speaking as if she were Mrs Bouquet. Aside from this mannerism, I cannot remember meeting anyone who had a posh voice. It was not until I was aged seventeen that I visited the Ascot home of posh schoolfriend Kate Graves and asked why there was a bell button in every room, only to be told that it was used to call a servant from the scullery. Okay, I thought to myself, I must have passed into a parallel universe.

My first indication that posh people and radio were a match made in heaven arrived when I was sharing a landing with a Durham University final year music student who had heard me regularly rabbit away about my passion for radio. One day he startled me with the news that he had accepted his first job as a producer on BBC radio. I was gobsmacked. Why? Because he had never once shown an interest in radio or demonstrated any understanding of how radio programmes are produced. I was pleased for him … but I was baffled. He had not been hired as a trainee. He had been hired to produce radio programmes without apparently having what might be considered the relevant skills to do the job. Months later, I looked in ‘Radio Times’ and, sure enough, his name was listed as producer of major daytime programmes on BBC Radio Three.

Perhaps this event, which seemed insignificant at the time, had been sent to me as a sign. Perhaps the gods were telling me that I should heed their advice, that I must stop believing in ‘meritocracy’ and that I should find myself a career ambition other than radio. If that was the case, I stupidly ignored their heavenly intervention. As a result, I expended a huge amount of effort during the next three decades, making dozens of applications for BBC radio job vacancies, being interviewed for many of them, but always being rejected. On occasion, I knew the person whom the BBC appointed and I knew the brevity of their CV … but they did possess a posh voice.

Fast forward to 2009. I was crossing London’s Shaftesbury Avenue in the company of John Myers, for whom I was writing a report for the British government’s Digital Britain initiative. Having finished a work meeting together in a nearby café, I was about to catch an Underground train home, whilst John was heading to his chauffeur-driven car. As we stood on the kerb, waiting for the traffic lights to change, John said something casually to me that started with the words: “Posh boys like you …”.

I immediately laughed out loud. Without thinking, my reflex action was to declare to John: “I’m not posh”. The words fell out of my mouth immediately without considering any potential consequences.

“Really?” said John.

“Yes,” I said. “I was born in a council house and went to school on a council estate. I am definitely not posh.”

“Oh,” responded John … and then we moved on to discussing other topics.

On my way home, I reflected on why John might have thought I was posh. He had a broad Lancashire accent and could never himself have been described as posh. He had worked his way up the radio industry from a start as programme assistant in BBC local radio in 1980, ending as chief executive of Guardian Media Group Radio in 2008. I could only guess that most of the people John was meeting at his present level of work were undeniably posh. He had been commissioned by the government, its ministers and its civil servants to produce a significant report on the regulation of the commercial radio industry in the digital age. Almost every one of his contacts for this work must have been posh. Perhaps, to him, I appeared to be just another of these posh ‘boys’.

Whatever the reason for his off-the-cuff comment, I sensed during the weeks and months that followed, that John’s attitude to me altered perceptibly. He continued to hold daily conversations with me by phone, email or in-person, as was necessary for me to ghost-write his report. In parallel, he had regular conversations and meetings with senior people in the radio industry, government and the Civil Service. But I was never invited to meet any of these people, even though it would have proven a lot more productive for me to have taken notes at these meetings rather than having to wait for John to relay me their content and outcomes. John convened and met regularly with a ‘committee’ of seven senior people and with a separate ‘consultation group’, both of which are listed at the end of the written report. I was credited merely with ‘research and support’, despite having transformed John’s handful of pages into a coherent 104-page document.

As a result of the report, John was invited by the radio industry to give the keynote speech at the 2009 Radio Festival event. As with the report, John sent me his drafted notes in advance, which I converted into a speech and an accompanying presentation. He did not invite me to attend the event. One morning, I woke to hear the bedside radio on BBC Radio Four broadcasting a live interview with John concerning the report. Once the written work had been completed, John did not keep me informed of the publicity it was receiving or its impact on government policy.

I was disappointed. John had needed my skills to research and write what came to be known as ‘The Myers Report’. However, after our ‘posh’ conversation, he had been careful to keep me away from the radio industry people who might prove useful contacts for me to find a job in radio, but who might see that it was really me writing the report rather than John himself. I understood how difficult it must be for a significant document bearing your name to be ghosted by someone else who had never been chief executive of a radio business, as he had, and by someone who was not even posh like his peers.

I consider John an example of how ‘posh’ not only commands respect amongst similarly posh people, but equally from people who are not at all posh. Posh equals clever. Posh equals superior. Posh equals special. Posh equals the ability to make people of every class believe you deserve to be treated as someone who can rule, can manage, can order, can tell the rest of us what we do. Whatever comes out of a posh person’s mouth is believed and, even if evidently untruthful, is retained as ‘gospel’. Posh people maintain their superiority only because the rest of us let them, encourage them and look up to them in the master/servant, upstairs/downstairs deference we have implicitly imbibed since childhood. Posh is superpower.

I had worked with John only as a result of sending him an e-mail attached to an analysis paper for MA studies that I had written earlier about the same regulatory aspect of radio for which his report had been commissioned. He had offered me a £10,000 fee to provide research support. Very quickly, my responsibilities went much further and led to five months full-time work on this report, during which time I had to reject offers of other freelance work. I shared my concerns with John that my work with him had deprived me of income and he promised that, although I was underpaid for this commission, he believed it would lead to further reports on which the two of us could continue to work together. He recognised that we had complementary skills and we worked well together.

The first negative signal arrived when I invoiced John for my fee once the report had been published by the government. I was registered with HMRC for VAT (sales tax) and was legally required to add an additional 17.5% to my invoice. John responded that he was not registered for VAT and therefore could not reclaim any VAT he might pay to me. As a result, he did not want to pay the VAT on my invoice. This response confused me. I had no knowledge of the amount he had been paid by the government to write the report that I had just ghosted for him. I was certain it must be at least ten times the fee he was paying me. He was disputing a payment of £1,750 that was required by tax law, when he had probably earnt one hundred times that sum for the same work. I persisted but he refused steadfastly to pay the VAT of my invoice. I was not at all happy.

In 2010, I read in the news that John had been commissioned by the BBC to write a report about its radio services. This was exactly the kind of further work that John had promised me and which I was hoping to be considerably more lucrative for my contributions. I met him at a café near Broadcasting House to discuss this next project. Initially, he wanted to know about the online blog I had been publishing since 2008.

“How much are you paid for your blog?” John asked me, betraying his lack of understanding of online social media platforms.

I had to explain that a blog pays nothing but its author hopes that their online presence would lead to connections, work and income in the long run. It was a marketing exercise, but intrinsically unprofitable. He still seemed enthusiastic.

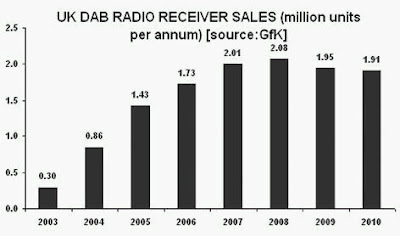

“How did you get your book published about DAB?” John asked.

My anthology of blog pieces about DAB radio had just been self-published as a book, so I offered him a free copy and explained the basics of creating a book for sale online and in bookshops. He seemed intrigued by the potential. Finally, our discussion moved on to the BBC report which John had been commissioned to write. My expectations were high. I was excited by the prospect of much needed work.

“You will not be involved in this report,” John said suddenly. “But I hope there will be something we can work on together in future.”

I was in shock. So much shock that I cannot recall the remainder of the meeting. I left feeling disappointed, deflated but mostly … betrayed. I had had to reject work the previous year because of the intensity of work on our last report. I had been paid a pittance. I had been promised work that now had not materialised. Because of the minor contribution with which I had been credited in the last report, I had received no unsolicited approaches to write similar reports. My work had been unacknowledged, unrewarded and now I felt I had been side-lined altogether.

I never received further offers of work from John Myers. But he started publishing his own blog about radio, much like mine. Imitation may be the sincerest form of flattery … but it does not pay the bills. Eventually I noticed that, in his blog, John was citing analyses of radio data that I had done and published in my blog, but he was neither crediting me nor linking to the source. As a result, I stopped publishing further blog entries after August 2011. It seemed pointless offering John further examples of my skills in analysis for him to claim the credit and make money.

In 2011, John Myers was appointed chief executive of The Radio Academy. In 2012 he was appointed visiting professor at the University of Cumbria. He published his own book about radio the same year but did not send me a copy.

At a Tribunal in 2015, John Myers was found guilty of tax evasion on earnings of £6.3m in 2005/6, for which he had paid only £130,000 in tax.

[Originally published at https://peoplelikeyoudontworkinradio.blogspot.com/2023/02/one-door-opens-another-is-closed-by.html]