The question of which digital radio broadcast standard should be adopted in France continues to be an issue of growing concern, even as the proposed launch in 2010 nears. According to l’Humanite, Socialist Party deputy Jean-Marc Ayrault has written to Culture Minister Frederic Mitterand, questioning the risks for local radio owners involved in the Ministry of Culture & Communications choosing a single digital radio standard. According to Ayrault, the decision in 2007 by then Culture Minister Christine Albanel of “T-DMB in Band III as the sole [digital radio] standard is worrying stakeholders more and more of the value to have chosen only one standard between T-DMB and DAB+”. Ayrault noted that tests by local radio groups in Nantes had demonstrated that “the joint implementation of both standards is technically possible”.

L’Humanite commented that “the launch of digital terrestrial radio is being complicated by a real scepticism, almost mistrust, in the notion that it can be started in early 2010”. The Ministry of Culture & Communications is due to present to the government a delayed second report on the proposed rollout of digital radio.

Tag: radio

AUSTRIA: media regulator puts DAB radio on hold

On 3 November 2009, the Austrian media regulator RTR presented the results of a study that had been commissioned in December 2008 on the potential for digital radio in Austria. Dr Alfred Grinschgl, managing director of RTR, commented: “The reason we in Austria are not presently digitising radio is that, in neighbouring Germany, there is no unanimous agreement on adopting DAB or DAB+ and therefore no successful large-scale launch.”

ORF, Austrian state radio, technical director Peter Moosmann commented that the time was not yet “ripe” for the introduction of digital radio and he rejected the notion of planned FM switch-off. “In every Austrian household, there are four or five radio sets that would need to be replaced with one blow,” he said. “We do not want to force the listener to switch, but want to entice them to digital radio with the appeal of new radio formats”.

The chairman of the association of Austrian private broadcasters, Christian Stogmuller, said that the successful launch of digital radio in Austria could only happen under a single European-wide technical standard, the existence of sufficient digital radio devices in the market and a significant financial commitment from public funds to launch digital radio.

The Austrian Association of Free Radios, VFRO, said it was sceptical because DAB/DAB+ is designed for large-scale radio services, whereas it suggested alternative technologies such as the DRM+ system be used for expanding local radio.

Michael Wagenhofer, managing director of transmission company ORS (60% owned by ORF), said: “The introduction of a digital radio transmission standard will require simulcasting [broadcasting content on both analogue and digital] for about 15 years because the car industry alone has a six-year implementation cycle”. He estimated the cost of building DAB multiplex infrastructure in Austria would be around 8m Euros.

Dr Grinschgl of RTR said that the anticipated carriage cost of DAB transmission for a local station would be around 100,000 Euros per annum, and that nationwide coverage on DAB would cost 800,000 Euros per annum. He warned that, if individual stations had to bear the costs of broadcasting on both FM and DAB, then DAB would develop only “very slowly”.

Back in June 2008, an ORF article on digital radio had noted: “The reason for the lack of consumer interest in digital radio is that RTR [the regulator] licenses a good range of conventional analogue radio services. The consumer is more than satisfied with the existing diversity of content and the quality of reception”.

Meanwhile, at the Media Days event in Munich this week, Jurgen Doetz, president of VPRT, the German association of private broadcasters, was reported to have proclaimed: “Digital radio is dead, dead, dead”.

DAB radio: "let us get on this horse or get off it"

House of Commons Culture, Media & Sport Committee

“The future for local and regional media”

27 October 2009 in the Thatcher Room, Portcullis House

Andrew Harrison, chief executive, RadioCentre

Travis Baxter, managing director, Bauer Radio

Steve Fountain, head of radio, KM Group

[excerpts]

Mr Tom Watson: Can I ask you about Digital Britain and the Digital Britain Report? Do you think the report gave a good way forward for the commercial sector to journey out of its current troubles?

Mr Baxter: Perhaps I could ask Andrew to give an overview on that and then maybe we can give our respective views?

Mr Harrison: To give an overview, I think the short answer to that is “yes”. One of the fundamental issues the sector faces right now is the appalling cost of dual transmission. Ultimately, right now, this is a small sector and very many of our stations are simultaneously paying for the cost of analogue and digital transmission. That clearly does not make any financial sense. What we advocated for in Digital Britain was a pathway for all stations to end up with a very clear plan of what is the single transmission platform for them. That led, as I said in my opening remarks, to three very complementary tiers of the commercial radio offer. The first tier is a strong national offer on digital to compete with the BBC, and that is critical for the sector because the truth is that the FM spectrum is full. I am sure all of you will know from some of the other conversations we have had before that the BBC dominates the gift of analogue spectrum. It has four national FM stations; we only have one with Classic FM. For the sector to compete and capture its share of national advertising revenue, the ability to have a national digital platform I think is critical. As we then had the conversations with Digital Britain, I think it became very clear to all of us that you cannot just migrate national stations to digital and leave all of the large metropolitan local stations, like City in Liverpool for example or Metro in Newcastle, all the BBC’s local stations, as analogue only. The listeners to those stations will want the functionality, experience and benefits that come with digital. It is then very important that we have a second tier of the large local and regional stations which also migrate to digital. Critically, however, that nevertheless leaves an important third tier, which are the smaller or the rural stations for which either DAB coverage is currently not present – there is just not the transmitter build-out in some of the rural areas – or for which it is likely to be prohibitively expensive going forward. That sector equally needs clarity and that sector being able to stay on FM alongside community radio we feel gives a very balanced ecology where the sector has the most opportunity to compete and the lowest cost base because each station can ultimately choose whether it is on one transmission methodology, i.e. digital, or another, analogue. At the moment, we are in limbo where stations are paying for both but the profitability of the sector is fragile and there is not a plan. So we absolutely welcome the beginnings of that plan, which we recognise is the start of what is going to be a long and difficult journey as stations migrate and decide if their future is on digital only or their future is on analogue. The quicker we can move the industry there, clearly the better for the fragile economics of the sector.

Mr Baxter: Perhaps I can encapsulate some of the things we sent in to the Carter Review. Our business view generally is that the future is digital. There is hardly the need for me to make that clear to you. Our view has been for the last ten years that we will look at all platforms as we develop our business. We have successful radio stations, primarily operating for example off the audio channels on the Freeview digital television system. However, within that we think it is of real value for radio to have a bespoke platform and the one that is available to us that is a bespoke broadcast platform is DAB. It has, however, taken 12 to 13 years of very slow development for that platform to get to its current state. Therefore, our proposition to Carter’s Review was: let us get on this horse or get off it. We think we should get on it and put every possible energy we can over the next view years into getting consensus, direction and pace into the whole process of take-up, like there has not been during the last 12 years. If that can be achieved, it will produce a new resonance for commercial radio as a whole, indeed for the whole of radio. It will help position radio more effectively in the fragmenting media landscape we all have to deal with and give us an opportunity, as Andrew said, of clarifying our investment levels around platforms where currently we are having to pay for two when, in a future where either one is successful, we would only have to pay for one, thereby allowing resource to be put into developing content and other things around our business.

Mr Fountain: KM Group does have a digital platform. It is currently costing us over £100,000 a year and we get absolutely nothing back from it. I think the company at the time, six years ago, took the view that they wanted to be a part of the future. Circumstances since have not really helped them to be able to develop that particular medium. I think we too take the view that we would want to be part of a digital platform going forward, but there are a number of issues that would need to be overcome, not least of all the cost of entry and also in our particular case our DAB coverage and the coverage of our FM stations is not mirrored. We have better coverage right now on our FM platforms than we do on our one single DAB coverage. The problem around the coast, if you take that from Medway right the way round perhaps as far down as Rye, around the Kent coast and just touching into Sussex, is such that DAB does not actually reach into large parts of that coastal area.

Mr Watson: Would DAB+?

Mr Fountain: I could not answer that because I do not actually know.

Mr Harrison: No, there is no difference in terms of the coverage for DAB or DAB+. DAB+ is just a different method of compressing the signal so you can actually get more signal down the pipe, if you like; you tend to get more stations, but it does not actually affect the coverage.

Mr Fountain: You can see that in order for us to extend the coverage of DAB, there is clearly a cost involved, and there is also a conversation to be had between Ofcom and the French communication authorities as well.

Mr Watson: Presumably you are all relatively happy with what is quite a demanding timetable outlined in Digital Britain if your view is that we should just get on with it and do it?

Mr Harrison: I think you have expressed it exactly right. The timetable is demanding. I think it is set deliberately as being demanding. Digital Britain does not set a date for switchover. What it sets are two criteria that it says are axiomatic to be hit before switchover can be contemplated: one on listener levels and one on coverage, both of which we support. The aspiration in Digital Britain is to try and hit those two gates, if you like, by the end of 2013. On what Travis was saying earlier on, we think that is absolutely right, that the industry now works terrifically hard together, alongside the BBC and alongside the Government and the regulator to do our very best to hit those criteria. Once we then hit the criteria, the Digital Britain report identifies that it will probably take a couple of years from the criteria being hit before we could actually contemplate switchover. That is aggressive but we think it is appropriately aggressive against the context of an industry that is clearly struggling financially now, and the vast majority of my members are highlighting the cost of dual transmission as the single biggest cost issue that they face and self-evidently one that could be eliminated the quicker we can get to a decision one way or the other.

Mr Watson: May I ask you a bit of a left field question? You are quite confident that we should move to digital radio quite quickly. How confident are you that consumers will want to make that journey and that they will not migrate to internet, radio or choose to listen to live streaming sites like Spotify?

Mr Harrison: There are two different points there. We are quite confident, as you say, about the movement to digital, but purely because what the Digital Britain Report sets up are consumer-led criteria to drive that change. The criteria are absolutely that we will not move until coverage is built out to match FM. It would be absolutely suicidal for the industry to switch people off who currently listen and enjoy radio services, so it is axiomatic that we have to build coverage out. Secondly, the criterion is that listenership to digital has to be that the majority of all listening has to be to digital before you would contemplate switchover. We are not going to rush into this without being led by the consumer. What we are trying to do, as Travis said earlier, is inject some pace, momentum and energy into the process. If we wait for the natural replacement of sets and the natural progression of DAB – it has taken a long time to get to the listener levels we have right now, we still have all of the BBC’s services for example available on analogue – it is going to be very difficult to kick start the progression. We are very comfortable but we are comfortable because it is led by the consumer. The second part of your question is: are we worried about competing services? We are absolutely. I think there is a whole generation of new entrants into the market – Spotify, Last.fm, Pandora – available on-line, all of which are unregulated and against which we are competing for listeners and for advertising revenue. When you have a small, heavily regulated, constrained local radio sector competing with an unregulated world-wide series of music offerings, that is one of the challenges we have to face. We are, however, absolutely committed to the importance of a broadcast transmission methodology for digital. That is not to say that the internet will not be an important complement to that but our business model is based on a broadcast signal of one signal to a wider audience. There is very little evidence so far that on-line music offerings are in themselves profitable business models. For UK citizens and consumers, for our listeners, we think it is absolutely critical that radio remains free at the point of delivery. That has been one of its great strengths ever since the BBC was founded in the 1920s. Of course at the moment, although as I heard this morning the cost of broadband is potentially down to £6 a month, nevertheless, to access any internet-delivered service, you have to pay an ISP connection. That may change but I suspect we are a long way away from that.

[edit]

Mr Watson: Do you think the car industry is sufficiently prepared for the digital revolution?

Mr Baxter: I think we have had some very encouraging conversations with the motor industry over the last six months. The response to Carter’s work during the beginning of this year has helped galvanise interest in that area quite significantly, so I think there is a very different aura around those discussions than there was 12 months ago.

Mr John Whittingdale, Chairman: Just on the cost of the digital upgrade, what is your best estimate of how much it is going to cost?

Mr Harrison: I was on the working party, the Digital Radio Working Group, that was the forerunner for Digital Britain. That working group identified the cost of build-out, the one-off capital cost, as between £100 million and £150 million. That is quite a spread. The reason for the spread ultimately depends on what degree of coverage build-out you get to from equalling FM to universality and at what signal strength. Of course, you get real diminishing returns as you go to the very rural areas. That is the reason for the spread. There has been a lot of debate about that number. In reality, the way we have tended to look at it is that if you take that spread of £100-£150 million over the 12 year period of a licence, which is typically when a radio station is licensed or a multiplex is licensed, and if you said for round figures it is £120 million, that is £10 million a year for the licence period. I think it was £10 million a year that the Secretary of State quoted for example last week. Funding that we have always felt is actually absolutely critical to the build-out and conversation to Digital Britain. The commercial sector is absolutely happy to pay its way to the extent that the build-out is commercially viable but, after that, there is a clear public policy imperative. If the Government and Parliament decide that it is important to have a dedicated transmission structure for radio, that will be a public policy decision and it will need funding. That said, we believe that funding is very affordable. If you take that £100 million number, we believe that, for example, the BBC would save much more than that over the period of the 12-year licence just on what it will save on FM transmission alone, so there is a straightforward business proposition. Another way to think about the £100 million over a 12-year licence with the current Licence Fee settlement for the BBC at around about £3.5-£3.6 billion a year is that over 12 years that is £43 billion. The £100 million infrastructure cost for DAB radio is less than a quarter of one per cent of what the BBC’s income will likely be over the next 12 years. So it is eminently affordable if there is a public policy decision that it is important to do that build-out.

Chairman: Those two arguments suggest that you are looking for the BBC to pay for this.

Mr Harrison: We have said very clearly and very fairly that we are absolutely happy to pay our fair share in our way to what is commercially viable.

Chairman: What does that mean?

Mr Harrison: That means that we have already put our hands in our pockets substantially to build out coverage on a local and a national basis as far as we judge is affordable. I think realistically, given the state of the sector, the vast majority of the cost going forward, which is primarily designed to meet the BBC’s obligations of universality rather than the commercial sector’s obligations of viability, should rest with the BBC.

Chairman: So whilst RadioCentre is keen to move ahead with the digital upgrade, the economics of your sector at the moment means that you cannot really afford to put any more money into it?

Mr Harrison: We believe that transmission coverage build-out is axiomatic; it is one of the criteria to effect switchover. We cannot afford it but we absolutely believe the BBC can.

Philip Davies: Andrew, on this part can I ask you about how representative your view is of the industry as a whole? It was over this issue it seems more than any other that UTV Radio quit the RadioCentre and said that it felt that it was no longer representing the interests of the wider industry and gave too much power to its biggest member.

Mr Harrison: Yes, UTV did say that. Scott Taunton, the UTV Radio managing director, actually represented the commercial radio industry with me on the Digital Radio Working Group through all the per-work that was done for Digital Britain, and so they have been intimately involved. To be fair to UTV’s position, they have a particular reservation over the date and the timing for digital, but to be fair to the Digital Britain Report, and indeed we await the clauses of any potential Bill because it is not yet written, there has never been a formal switchover date actually agreed. Although, for example, I think Scott in his Guardian article yesterday talked about a 2015 date being farcical, that date has never been set. What have been set are two consumer-led criteria that have to be hit and then a transition period after that before we all migrate. As Travis said earlier, the majority of opinion across the sector, and certainly across my members and representing my board, is that we need now to put our foot on the gas and work hard to deliver the criteria. Inevitably, there is going to be a spectrum of views with different businesses in different places in terms of their own business models as to the urgency or not they see behind that. UTV are absolutely right to have their own position. They are more at the tail end of the timing.

Philip Davies: UTV did not just say that they had a different position to you. They said something a bit more fundamental than that that they felt that you were no longer representing the interests of the wider industry. It was not just as if they had a disagreement. They were indicating that there were others in the sector who shared their view. Do you accept that there are many others or some others in the sector that would share their view?

Mr Harrison: I would absolutely accept that we are a broad church and there is a breadth of opinion. I represent large and small stations, local and national, rural and metropolitan, so there is a breadth of opinion. To give you an example of that, our other major national station member that is on AM is Absolute Radio and they believe that the timing for digital should be sooner rather than later. They already have over 50% of their listening on digital platforms, one way or another, so they would move sooner. I have a number of digital-only stations in membership, stations like Jazz and Planet Rock, which clearly are already digital-only and would like to be in the vanguard. Inevitably, there is a spectrum of opinion and we try our best to reflect the overall views. The truth is that it is very unfortunate that UTV have left membership but we continue to represent the vast majority of the sector and its stations and will continue to try to steer a path, helping Government and helping the regulator through this tension.

CATALONIA: DAB radio in a "coma"

A new 176-page report documenting the current state of radio broadcasting in Catalonia (the autonomous region in Northeast Spain with 7.4m population) says that DAB radio “is in a state that could qualify as a technical coma”, according to infoperiodistas. Of 48 licences awarded by the media regulator for DAB radio, only 23 stations are presently broadcasting and are reported to have no impact on radio audiences.

Digital Radio Upgrade & the Digital Economy Bill

Westminster eForum Parliamentary Reception

Terrace Pavilion, House of Commons, London

28 October 2009 @ 1600

“The informal discussion that takes place can be expected to cross a range of current policy issues but the chosen theme is digital switchover and DAB.”

JOHN WHITTINGDALE MP, Chairman, House of Commons Culture, Media & Sport Select Committee:

The future of radio is very much a topic under debate. My Select Committee is currently conducting an inquiry into the future of local and regional media, of which radio is an absolutely critical part. So yesterday we were hearing evidence from Andrew Harrison of RadioCentre, Travis Baxter [of Bauer Media] who is here somewhere today, and Steve Fountain from KM Group. And we are very much aware of the pressures on commercial radio and the difficulties faced. But, at the same time, there are opportunities. And when Digital Britain came out, much of it had been trailed in advance, a lot of it quite controversial – things like top-slicing and file-sharing legislation – but the one bit which came as something of a surprise, I think, was the announcement of the date for Digital Radio Upgrade. Certainly, when I saw that in the Report, my immediate reaction was rather like the ‘Yes Minister’ Permanent Secretary who said: “That is a very brave decision, Minister”.

It is going to be challenging. It is slightly controversial. Not everybody in the industry is 100% yet signed up to it. Equally, there is a cost attached and we can have interesting debates about who is going to pick up the bill for it. And there will be quite a task to persuade people. In the same way that we had to work hard to persuade people that analogue switch-off of television was going to be beneficial, I think the task to persuade people in the case of radio is going to be even greater, particularly whilst we still have the overwhelming majority of cars with analogue radios in them. So there are challenges, but equally there are going to be benefits.

We heard yesterday about the costs to radio of having to transmit simultaneously in both analogue and digital and, clearly, that is something which would be reduced if we managed to get switchover. So this is a very important debate and I am keen that, when we come to debate the Digital Economy Bill when it is introduced, we should not overlook radio. There is always a danger that everybody focuses on television and there will be a huge argument about whether or not the BBC should be the exclusive recipient of the Licence Fee, and whether or not we should be trying to stop teenagers in bedrooms file-sharing, but it is important we should also debate radio and, certainly, that is something which I will try and do my best to ensure happens. But I think this afternoon is a good start to that and it is good to see so many people from the industry assembled in one room. So that’s enough from me, just to say welcome to the reception this afternoon …..

PAUL EATON, Head of Radio, Arqiva:

I would like to welcome you all as well on behalf of Arqiva and Digital Radio UK. Arqiva is part of Digital Radio UK, with the BBC and commercial radio, and I am very pleased to be joined today by Andrew Harrison, chief executive of RadioCentre, and Tim Davie, director of Audio & Music at the BBC.

Digital Radio UK has been formed by the radio industry to get the UK ready for the Digital Radio Upgrade. That upgrade is vital because radio faces a stark choice – we can either stay in the analogue world or we can move forward into the digital one. Both need considerable investment from all of the players but only one, digital, can give radio that exciting future that listeners deserve. Digital radio will mean more choice, a better quality listening experience and the kind of interactivity that we can only dream about today.

We all know that the road ahead is a difficult one. We know that the coverage is not good enough yet, we know that we haven’t got digital radio in enough cars, and we know that we need to get converters onto the market to turn analogue radios into digital ones – set-top boxes for radio, if you like. We know that there is new content and new services that need to go digital. So there’s a lot to do. But, in creating Digital Radio UK, the radio industry is demonstrating that it is serious about the digital future and is determined to address the issues and, in doing so, give the digital future that listeners deserve.….

SIMON MAYO, Presenter, BBC Five Live:

I had one of those “blimey, you’re old” moments this morning. I was talking about radio with my son – my eldest son is eighteen – and I asked him what he listened to and what his friends listen to. He thought for a moment and then he said “none of my friends have got a radio”. I thought that was quite an astonishing moment. Now, obviously, he is an unrepresentative sample of one, that is true. They kind of know about radio and they might listen online, and it’s on in the kitchen and they hear it in the car and they have an opinion of [BBC Radio One breakfast presenter] Chris Moyles, but that was it. It occurred to me that, really, radio has got a bit of a fight on its hands, which is where the kit here [points to display of DAB radio receivers] comes in, I think.

My parents’ generation didn’t need to be told that radio was fantastic. My father, if he was here, would talk about listening to Richard Dimbleby and Wynford Vaughan-Thomas and The Goons. The Goons generation didn’t need to be told that radio was great. The 60s generation didn’t need to be told that radio was great – they had the pirates, then they had Radio One. My generation fell asleep listening to the Radio Luxembourg Top 40 on a Tuesday night. It finished at 11 o’clock and that was quite daring – I see a few people nodding. That was quite daring staying up to 11 o’clock, and the fact that is was sponsored by Peter Stuyvesant cigarettes was even more dangerous. But we remembered it and we fell in love with radio, and I think there is a job to be done to make future generations fall in love with radio.

So enter digital. Partly that has to be done by the broadcasters in coming up with exciting new stations filling gaps that don’t exist. BBC7 is wonderful. Everybody will have their own particular favourites. Absolute Classic Rock is really rather good. If you want Supertramp and Led Zeppelin any time of the day, that’s the place to go. Really good stuff. There are some really big gaps that need to be filled, but that’s exciting. Analogue is full, so digital is the place to be.

But the kit is really exciting. If you have a radio when you are listening to a piece of music …. and you’re listening to the radio and an Angelic Upstarts track comes on, you press a button and it sends you an e-mail that tells you that they have reformed, you can buy their records and this is where they are playing. Or someone is listening to ‘Yesterday In Parliament’ and they hear a speech from a parliamentarian that they like, and they think “he’s interesting, she’s interesting”, press a button, you get sent an e-mail and it tells you who it is, how you can contact them – this sounds quite exciting. If you are listening to one of [presenter] Mark Kermode’s film reviews on Five Live, and you like the sound of the film, you press a button, and its sends you an e-mail, you go to your in-box and it’s got an e-mail telling you where that film is on, how you can go to see it, maybe a link to the trailer. All of that kind of information means that radio has got an exciting future, but it just means that we have to go out and explain it a bit more because people might not get it the way they used to.

Hopefully, there is still a role for the humble presenter. So you do a little bit as well. Thank you very much indeed for coming…..

[A Digital Radio UK factsheet entitled “A briefing on the digital radio upgrade” was distributed at the event. Click here to view.]

Digital platforms: commercial radio losing share to BBC

Today’s RAJAR data demonstrates that a gulf is opening up between BBC radio and commercial radio in their ability to attract listening to digital platforms. Over the last year, the BBC is accelerating away from commercial radio in its audience’s usage of DAB, digital television and the internet to listen to live radio programmes. The significance of this growing gulf is reinforced when one remembers that the main RAJAR survey, from which the data below is taken, only measures ‘live’ radio listening and does not incorporate listening to either time-shifted, on-demand radio (‘listen again’) or to downloaded podcasts, both forms in which the BBC offers a much greater volume of content than UK commercial radio.

The danger here is that the BBC is poised to dominate listening on digital radio platforms in the long term, exactly as it already dominates listening on analogue radio platforms. One of the main reasons that the commercial radio sector invested so heavily in digital platforms during the last decade was the opportunity it offered to compete more effectively with the BBC for audiences. In the analogue world, the commercial sector has always argued that the BBC (having been there first) was allocated more and better spectrum for its radio stations. ‘Digital’, particularly DAB, seemed to offer the commercial sector a chance to ‘even the score’ with the BBC. The RAJAR data show that this ambition is not succeeding.

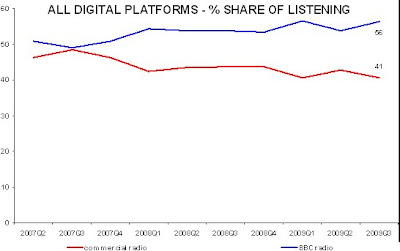

Across all digital platforms aggregated, commercial radio is losing ground, with the latest quarter (Q3 2009) reducing its share of listening to 41%, versus the BBC’s 56% share.

Taking each digital platform in turn, commercial radio’s share of listening on the DAB platform fell to 33% in Q3 2009, compared to the BBC’s 65%. This is not surprising because the age profile of DAB purchasers tends to be older listeners who are statistically more likely to listen to BBC stations. However, it does pose a grave question as to the return that commercial radio can expect from its substantial investment to date in DAB infrastructure, if listening on that platform is dominated so much by the BBC.

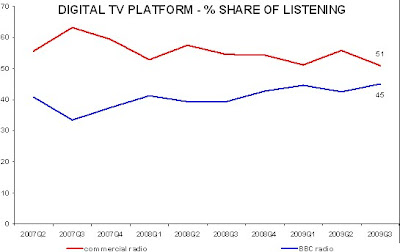

The digital TV platform is one that commercial radio has long dominated because of the large amount of spectrum it leased in the early days of Freeview. However, the increasing popularity of digital terrestrial television has already substantially increased the cost of spectrum on Freeview for the radio industry when its contracts come up for renewal. Furthermore, the forthcoming re-ordering of the multiplexes to accommodate HD television and new compression codecs is likely to squeeze commercial radio’s access to Freeview spectrum even more so. Before long, it is likely that the BBC will dominate the digital TV platform, just as it already does on DAB. Presently, the BBC has a 45% share, compared to commercial radio’s 51%.

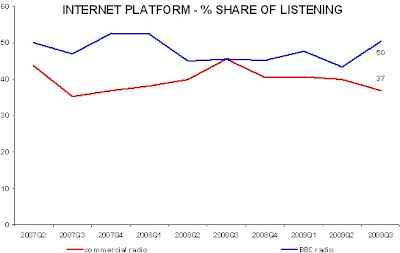

As might be expected, the BBC’s strong online presence has already put it in the commanding position in terms of its share of listening via the internet platform. The integration of BBC radio into the iPlayer has no doubt helped as well, whereas commercial radio’s offerings are relatively more fractured and less heavily marketed, despite the excellent innovation of the RadioCentre Player. The BBC has a 50% share of listening on the internet platform, compared to commercial radio’s 37%.

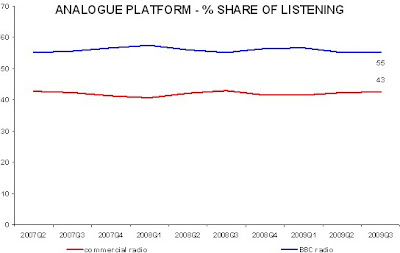

The significance of commercial radio’s diminishing share of these three digital platforms is demonstrated when we look at the two sectors’ listening shares achieved on the analogue platform alone. Once one removes the digital platforms from the picture, it is evident that the shares of both the BBC and commercial radio have remained relatively stable in recent years. In other words, it is commercial radio’s declining share of listening on digital platforms that is effectively pulling the sector’s total share of listening (analogue + digital) down, particularly as digital platforms are growing as a proportion of total radio listening (21.1% in Q3 2009).

There is a paradox here. The commercial sector invested heavily in the DAB platform, believing that the new technologies would help it INCREASE its overall share of radio listening versus the BBC. In fact, that investment has recently helped to DIMINISH commercial radio’s overall share of listening. Digital television remains the only platform in which commercial radio dominates, and yet this is the very platform where commercial radio will be forced to cede spectrum and face, once more, losing out to the BBC whose spectrum for radio is guaranteed.

It is important to emphasise that these graphs show only the SHARE of listening on these platforms. The volumes of listening on each of these platforms have demonstrated absolute growth for both commercial radio and for the BBC over the same time period. But, more than any other digital platform, it is significant that the DAB platform is dominated by the BBC which now accounts for almost two-thirds of its usage. Such data is important when making decisions about the potential returns on further investments in DAB infrastructure. Will further investment simply maintain the existing imbalance, or will it really improve commercial radio’s share? Does investment in infrastructure also require parallel investment in new content that will appeal directly to the older age groups who own DAB radios?

Some possible reasons for commercial radio’s diminishing share of listening on digital platforms include:

• Commercial radio’s tendency to invest in DAB infrastructure more significantly than in original digital-only content

• Recent closures of many digital-only radio stations in the commercial sector

• The BBC’s relatively stable resource base, at a time when commercial radio revenues are falling precipitously

• The BBC’s long-held policy to invest simultaneously in multiple platforms, whereas commercial radio has focused on DAB and, to a lesser extent, Freeview

• The BBC’s focus on creating exclusive digital-only content unavailable on the analogue platform

• The BBC’s 360-degree music royalty agreements which allow it to use diverse platforms, whereas commercial radio requires separate (and more restrictive) agreements for time-shifted content and podcasts

• The BBC’s long-term, consistent promotion of content and digital platforms across TV, radio and the internet whereas commercial radio is less willing to cross-promote content or digital platforms that migrate listeners away from its core analogue offerings

• Frequent management changes and ownership changes in some parts of commercial radio, where substantial consolidation has often translated into short-term ‘slash and burn’ rather than ‘invest and build’ policies.

Whatever the reasons, we are not where we were meant to be – that is, we are not where it had been anticipated more than a decade ago commercial radio would be when investment in digital platforms, notably DAB, was expected to produce a beneficial outcome for commercial radio audiences versus the BBC. To put it plainly, the strategy conceived in the 1990’s has not worked. Commercial radio offerings do not dominate digital platforms (yes, they are more numerous, but they do not attract more hours listened than the BBC). DAB has become a largely BBC platform.

So, what can be done? Some of the issues noted above require a more level playing field to be established between commercial radio and the BBC. One such example of a practical solution is the Radio Council plan for a new UK Radio Player that will offer BBC and commercial radio content from a single aggregated access point. Other issues remain mostly in the lap of the gods (revenues, for example). Some issues require the BBC to be less predatory (or more regulated) and for the commercial sector to be more focused on strategic, long-term objectives (such as an online strategy that is more than simulcasting).

There is no single answer to this complex problem, though the commercial radio sector is hobbled by both its present lack of profitability and the regulatory strings that are attached to the majority of its analogue radio licences. What is desperately needed in these difficult times is not minor regulatory tinkering (such as adjusting how many hours of local content a local station is required to broadcast) but a wholesale change in strategy to maintain a commercial radio sector that can thrive in the digital marketplace we now inhabit. Will the imminent Digital Economy Bill prove sufficiently forward-thinking in its radio policy proposals?

[Statistical note: The graphs above to do not sum to 100% because the minimal amount of platform data released by RAJAR is ‘rounded’ (hours listened to 1,000,000; listening shares to 0.1%) and the listening apportioned to the BBC and commercial radio sometimes does not add up to the total for a platform. Some of this shortfall may be accounted for by ‘other’ listening (neither the BBC nor commercial radio) which is not itemised by platform. Data for individual quarters are therefore somewhat inconsistent, though the trend over several quarters is likely to be indicative. Additionally, there is an element of radio listening unattributed to any platform, 12.8% of the total in Q3 2009, but which is roughly equally applicable to BBC radio and commercial radio.]

Culture Secretary speaks about digital radio

The House of Commons Culture, Media & Sport Committee

20 October 2009 @ 1100 in the Thatcher Room, Portcullis House

John Whittingdale MP, Chairman [JW]

Ben Bradshaw MP, Secretary of State, Department for Culture, Media & Sport [BB]

JW: You have announced very ambitious plans to deliver the Digital Radio Upgrade programme by 2015 and have most of the national stations to move off analogue to digital by then. That will require extensive investment in the digital transmission network. What estimate do you have of what it is going to cost to do that?

BB: The current estimate that we are working on is about, I think I’m right in saying, is it £10m per year to build out the DAB multiplexes? Is that the figure that you were interested in?

JW: Actually, the one I’ve heard is rather more than that. Where is that money going to come from?

BB: It will come from a mixture of sources. We expect the BBC to play a significant role in this, commercial radio, and there may be public funds as well.

JW: I think the current state of commercial radio means that their ability to invest any more is almost zero. Do you foresee, therefore, further government investment, maybe from the Licence Fee?

BB: We are not currently intending to spend …. [laughs] That’s one of the things we are not intending to spend a share of the Licence Fee on, but if there is an even bigger underspend in the Digital Switchover Programme than we are currently expecting, who knows, Mr Chairman?

JW: The Digital Switchover Programme appears to be earmarked for quite a large number of purposes.

BB: [laughs] Well, there is quite a significant underspend.

JW: But you are confident that it can be delivered. And what are you going to say to all the people that haven’t bought a new car in the last two years by 2015?

BB: We are working with the motor manufacturers, both to ensure that future new cars do [have DAB radio], but also to ensure that there is this – I can’t remember what it is called – but it is some sort of gadget that you will be able to use in your existing car to make sure that you can pick up digital radio. One of the things we say quite clearly is that we won’t go ahead with this unless, by 2013, certain conditions are reached ie: we have more than 50% digital radio ownership and that [DAB] reception on all of our main roads is not going to be a problem. So we have put conditions down but, at the same time, we felt that it was important to provide market certainty that we specified an end-date by which time this should happen.

[excerpt]

[A further meeting of the Culture, Media & Sport Committee will be held in the same room on Tue 27 October from 1030 to discuss “The future for local and regional media”. Andrew Harrison of RadioCentre, Travis Baxter of Bauer Radio and Steve Fountain of KM Radio will give evidence.]

GERMANY: National public radio to end DAB broadcasts year-end

At the end of September 2009, the Radio Council of Germany issued a public statement in which it objected to the withdrawal of further funding for DAB radio by the KEF [the organisation that allocates funds for public radio] in July 2009 (reported here) and it made a direct appeal to the Prime Minister to create an independent digital platform for radio broadcasting. It said the rollout of DAB+ to replace DAB would now be cancelled. It argued that the phased closure of analogue radio broadcasting between 2015 and 2020 was realistic and that the government should adopt a legal framework for digital radio migration.

Now, in an interview this month with ‘Digitalmagazin’, the director of Deutschlandradio (German national public radio) Willi Steul confirmed that its two national stations will end broadcasting on the DAB platform at the end of 2009.

Now, in an interview this month with ‘Digitalmagazin’, the director of Deutschlandradio (German national public radio) Willi Steul confirmed that its two national stations will end broadcasting on the DAB platform at the end of 2009.

Digitalmagazin: ‘Deutschlandradio Kultur’ and ‘Deutschlandfunk’ will not be available on DAB radio after the end of the year. What led to this bitter decision?

Steul: We need to face up to the fact that the KEF removed funding for further DAB broadcasting, including the DAB broadcasts of our two channels. This is all the more regrettable because DAB will no longer be available for the digital distribution of our new, knowledge-based, educational station.

Digitalmagazin: To what extent does this sound the final death knell for DAB?

Steul: So far, not yet. However, DAB – although vital – is in intensive care and living a sad, hospitalised existence. A paradoxical situation!

Digitalmagazin: We are meant to be re-launching with DAB+. Is this country making the transition to the age of digital radio, or will Germany remain an ‘analogue island’?

Steul: At the moment, we are on the low road to becoming a glorious analogue island. In the medium- and long-term, there is no alternative to the age of digital radio. Let’s see when the powers will be prepared to take responsibility for media policy and offer some certainty.

Digitalmagazin: The Radio Council has criticised the KEF decision as “unacceptable interference in the broadcasting policy of the German states”. Why?

Steul: The role of the KEF is to identify the financial needs of the public service broadcasters. Its job is not to forge media policy, even when there are fiscal issues, as with DAB. This is unacceptable.

Digitalmagazin: But is it not the responsibility of the KEF, in the absence of sound arguments – and this seems to be the case with DAB – to pull the plug?

Steul: You mean ‘economically’? If you invest properly for the future, you cannot expect immediate returns on your investment. The essence of investing is that money needs to be spent on innovation and a process of transformation that will only bear fruit at a later date. The digitisation of radio is, in many ways, a lengthy process and so it is premature to pull the plug now and jeopardise the investments made to date. This is definitely not economical!

Digitalmagazin: The [KEF] budget for digital radio has not been scrapped, but assigned to new initiatives. What options are there now for digital radio?

Steul: Digital radio is already available via cable and satellite. Also, internet streaming has a great future. There will be further developments, particularly in mobile internet access. At the moment, internet ‘on the move’ – in spite of flat tariffs – is still a very expensive pastime.

[cut]

Digitalmagazin: The Radio Council considers it is realistic to propose a switch-off of analogue radio between 2015 and 2020. How will this be achieved, given the estimated 300 million FM receivers in Germany?

Steul: It will not happen without appropriate incentives for the transition from analogue to digital. Such issues are not the major responsibility of radio people. They are an issue for media policymakers and receiver manufacturers. When people are offered something of interest to them, they will give up their old FM radios. Examples from other sectors should encourage us.

NORWAY: Government commissions cost analysis of FM switch-off

In April 2009, NRK [state radio] chief Hans-Rore Bjerkaas had written to the Culture Minister asking if the government could persuade consumers to purchase DAB radios rather than analogue radios. He wrote: “In order to reduce consumer disappointment in the final stages of digital migration, a clear political signal must be given that, when choosing a radio, an FM/DAB radio should be selected rather than a pure FM radio.”

Culture Minister Trond Giske responded: “My responsibility lies with radio listeners. There are two reasons why I think we should progress more slowly than with the introduction of digital TV. It will be more costly for consumers to switch to DAB because most people have multiple radio receivers. In addition, there is no significant improvement in audio quality. When half the population has purchased a digital radio, we would be willing to discuss a specific date for switching off the FM network.” At present, 17% of the population in Norway has a DAB radio.

This month, the Culture Minister reiterated that the government will not consider switching off FM until half the population has purchased a DAB radio. Both NRK and P4 [commercial network owned by MTG] have told the minister that their existing FM networks are expensive to maintain and that they want to move to DAB as quickly as possible. NRK spends NRK120m per annum on FM radio transmission. Transmission provider Norkring [owned by Telenor] says it will need to make a major upgrade to the FM network in 2014 to keep it in service. So the government has tendered for an “independent and expert” assessment of the costs associated with switching off FM broadcasts in either 2014 or 2020. The analysis will be part of the White Paper on digital radio to be published by the government next year.

FRANCE: “Digital terrestrial radio: now!”

Last week, three trade bodies in the digital radio sector in France jointly wrote this opinion piece published in Radioactu magazine:

“Digital terrestrial radio: now!”

Digital terrestrial radio has been a reality since 27 May 2009. A reality that came about through the decisions of the CSA [France’s media regulator], decisions that had been anticipated for many years by many commercial radio stations and associations who have submitted applications across France and who have made financial investments in the meantime.

These companies and associations were well aware of the digital radio standard that was chosen [T-DMB], despite controversy surrounding this decision, were also conscious of the need to simulcast [FM and T-DMB] during the period of migration to digital and, finally, were aware of radio’s need to digitise in order to quickly take its place in the converged media world, in the face of attempts by television and mobile phones to turn it into a minor player.

However, the reality of digital terrestrial radio is primarily the benefit to listeners of a significantly expanded radio content offering at local, regional and national levels.

In the first three areas selected by the CSA to launch later this year, the number of stations will increase from 48 FM to 55 digital in Paris, from 29 to 41 in Marseille, and from 27 to 40 in Nice.

The reality is also the opportunity offered to radio stations to expand their existing broadcast coverage areas and become, if they wish, multi-city stations or multi-region stations which would make them “new market entrants”, something that the unavailability of FM spectrum had denied them until now.

The reality is the introduction of new listener features unprecedented in FM radio. Sound quality equivalent to CDs. The ability to go back and listen to a whole show that has already been broadcast. The introduction of a visual mini-display on receivers that shows data associated with the show (station logo, photos of the host and guests, the CD sleeve or book cover…). As well as the interactivity offered by digital terrestrial radio in conjunction with internet and mobile phone networks is the ability to offer transactions connected to the broadcast show (music, concert tickets), to access travel information, check share prices, the weather …

Finally, the reality is the choice to offer “podcasts” and to benefit from the radio medium’s mobility to access free and accurate information.

These are all qualities which, like digital terrestrial television before it, will allow millions of French citizens to benefit from new content offerings which will always be free-of-charge.

However, in recent weeks, we note that those who, only yesterday, did everything to frustrate the adoption of DAB and the CSA’s call for licence applicants in 2000 to digitise the Medium Wave; those who refused the good sense to choose a common digital radio standard, preferring ‘multi-standards’ to European harmonisation, the American proprietary IBOC system and, more recently, the Korean T-DMB standard, are carrying on their ‘’ballet”, making incessant demands and all kinds of attacks upon the CSA, using delaying tactics to choose a standard that is anything other than the one they themselves imposed.

The big operators still feel they have an absolute monopoly, as if the radio landscape has not changed since the ‘liberation of the airwaves’ so that the landscape remains frozen, they can reject competition from new entrants, and can maintain the natural order and their enrichment.

But, despite these large players continuing their efforts to maintain their monopoly, they are today showing their weaknesses. They seem almost unable to create new offerings and new content when they know perfectly well that competitors are on their doorstep with new formats, new stations and a new radio spirit which thinks of radio as a multimedia experience which only digital terrestrial radio can make happen. The global radio medium has been born and it is the listener who makes the rules. It is the end of media that are imposed on the listener, as consumption habits are changing quickly (with a capital ‘Q’), but do the big operators get this? Above all, do they have the ability to adapt to this inevitable evolution? Anyway, even if their concerns are legitimate, their attempts to prevent the launch of terrestrial digital radio are not.

Today, it is no longer up to them to decide the future of radio in France. It is up to the public bodies, notably the CSA, to take responsibility for finally launching digital terrestrial radio, which had been decided by a call for licence applicants in March 2008. Many radio owners have been licensed and are ready to open their stations, just as there are many who could be ready to open new stations but who have not been licensed due to lack of spectrum.

We created the Vivement la Radio Numerique organisation in 2002, the Digital Radio Francaises committee in 2003, and the Digital Radio association in 2005. The first two have merged into the third to increase their productivity and to make digital terrestrial radio happen more quickly. All three are a legacy of the Club DAB and pay tribute to its president Roland Faure who, on the subject of DAB, expressed regret “that the processes for the digitisation of radio are blocked, despite the success of the call for licence applicants in 2000”, a subject on which all three organisations have spoken out.

We note with regret that, since 1996, politics has zig-zagged. The call for DAB licence applicants in 2000. The call for Medium Wave licence applicants in 2003. The adoption of a legal framework for the launch of digital radio in 2004. In 2005, Minister of Industry Patrick Devedjian made the statement that “digital radio is a high priority”. Then CSA President Dominique Baudis stated that “the Higher Council for Broadcasting will soon launch a consultation on digital radio, which will be the starting point of its launch”.

The call for digital radio licence applicants made in March 2008 in response to the strong demand (after numerous consultations with stakeholders, public meetings and technical tests). Progress had already been a long and winding road over more than a decade when, in May 2009, the powers that be finally intervened.

Any slowdown, postponement or delay will be very damaging to all existing operators, new entrants and future players who are all awaiting the launch of digital terrestrial radio. We will not tolerate further delays. Any further delay would be seen as a de facto cancellation of the licence awards made on 26 May 2009, which we would totally reject.

We cannot accept that the law can be constantly violated by a handful of players whose positions are constantly changing to turn digital radio into an imaginary illusion at the expense of listeners, our businesses, our organisations and our economy.

Radio is the only medium that has not yet been digitised. Digital terrestrial radio has been promised since 1996. It now exists in law, it has a legal framework, it is on the statute book, and the CSA has called for licence applicants and has selected the winners, all events that are in the public domain.

Everything is now in place for digital terrestrial radio to be launched. The system has been validated by the Ministry of Culture. The first three areas have been selected and the licence awards made. The public utility announced its intention to own and operate digital radio multiplexes. The contracts were sent to multiplex operators and the agreements were returned by the content providers. Commitments have been made to the ‘have nots’. The technical standards have been published for broadcasters and set manufacturers. Broadcasters have announced an incentive scheme for content providers to create multiplex owners. Set manufacturers are announcing their product lines.

Also, neither the current economic crisis, nor the internet, nor the fragmentation of listening habits (which go back more than 20 years) can justify a delay to the launch of digital terrestrial radio.

Any delay or postponement would risk thousands of jobs at a time when France, like many European countries, is trying to exit the crisis.

In these difficult times, only innovation and creativity count, and no lasting victory can be won by not following common sense.

The time is ripe to keep one’s promises and commitments in a spirit of self-discipline, necessity, will and, above all, responsibility or it will be need to be explained officially and publicly why digital radio was not launched, to name those who seek to prevent its launch in France, and to compensate the licensees.

Public broadcasters have been at the forefront of digital radio in Britain and Germany. In our country, it is high time that the public broadcaster comes out of the woods and takes on the responsibility, for which it has rights and duties to all our citizens: the right to pre-empt analogue and digital frequencies and the certainty of having its own multiplex to broadcast all of its channels to cover 90% of the country.

We must start digital terrestrial on time next December because nothing more should stop it and the various operators are ready. Those who do not want digital terrestrial radio have the internet solution. Radio is not only about market share or decades of radio experience, but about a wish to move the medium forward.

For us, digital terrestrial radio is now or never! We need to start with those who want it and they are many.

Those who do not want it, or who have filed applications lightly or by reflex but will not start within the period required by law, must take responsibility and return their licences to the CSA, who will re-advertise them to the benefit of the many operators waiting for digital licences.

Shalak Jamil, President of the Association Digital Radio

Tarek Mami, President of Vivement la Radio Numerique

Joel Pons, President of the Digital Radio Francaises committee

[unabridged]

My post-script:

A digital radio trade show and conference takes place 20 to 22 October at Hall 7.3, VIParis, Porte de Versailles, Paris. The “Siel-Satis-Radio” event is billed as a “series of meetings dedicated to digital terrestrial radio which will take stock of the questions and viewpoints of stations and the aid promised to radio groups”.