The prostitute was perched on the edge of my bed. Using the elementary Hebrew I had learned from children’s television, we chatted about her young daughter and the disastrous economic situation in Israel (inflation nearing 1,000%) that had forced her into this profession. I had been asleep in bed when the room door had opened, the light was abruptly turned on and I opened my tired eyes to see a ‘Little & Large’ couple framed in the doorway. Having ordered her client to take a shower before starting ‘work’, she had ample time for a conversation with me.

Was this another chapter of my punishment, to share a hotel room with a fat drunken Dutch sailor whose mission was evidently a missionary position in every port? I had come ashore after spending a week of nights sat alone on the ship’s bridge as ‘lookout’, tossed from side to side by the stormy Mediterranean. This was the sentence handed down by a Dutch captain angered by my point-blank refusal to enter the anchor chain locker alone and clean it of seabed debris. I cared not a jot that other DJs on board had accepted his prior orders to execute this task. I was adamant that I had not signed up as a seaman. I was there as a radio DJ. Neither the captain nor his crew had ever been required to assist us in the radio studios, so why was I expected to take on ship duties? Besides which, I suffered from claustrophobia.

Well, how did I get here? I had spent 1984 living at my mother’s house, unemployed and submitting applications for every UK radio production job I could find, none of which proved successful. All I had been offered was a six-month contract to work as a volunteer DJ on pirate radio station ‘The Voice of Peace’ in Israel. I promised myself that, if no proper job turned up by year-end, I would pursue this as a last resort. That was why, in the New Year, I was on a flight to Tel Aviv with two suitcases. It was sheer desperation. I had to convince myself that ‘doing radio’, almost any sort of radio, would be better for my career than trying to get work in radio but failing.

The deal on offer was that, for each month’s work on board the ship, I would receive US$100 in cash and be granted one week’s shore leave in paid Tel Aviv hotel accommodation. However, the seas proved too rough for crew transfers during my first three months on board, depriving me of returning my feet to land until April. It was particularly frustrating during that period to be able to clearly see the twinkling lights of Tel Aviv city at night from the ship but to have only spent a few hours there between my airport arrival and having been ferried on board.

The only ship I had experienced before was a cross-Channel ferry, so my first few weeks were spent being seasick and adjusting to the meals served by amiable cook Radha who professed he had pretended to be a chef to land this job. Initially there were plenty of DJs on board and my shifts presenting on-air were reasonable. However, as the months went on, most of my colleagues either completed their six months or quit early and were not replaced. There were occasions when I was required to present programmes for more than twelve hours a day when our number was reduced to two. I consoled myself that, detained in a floating prison, it was better to be kept occupied than to spend time reflecting on the notion of freedom.

Nominally in charge of the station’s programmes on the ship was the genial Daevid Fortune who, I seem to recall, had previously worked on Twickenham AM pirate ‘Radio Sovereign’, a station that had existed for eight months in 1983 playing only oldies. At the ripe age of twenty-seven, I was older than most of my colleagues and more experienced, having previously worked full-time for UK commercial local station ‘Metro Radio’ not only as a presenter but as a manager who had implemented an innovative playlist system to reverse its dwindling audience. However, within the ship’s radio team, I maintained a low profile as there was no incentive to propose improvements or seek additional responsibilities without decent compensation.

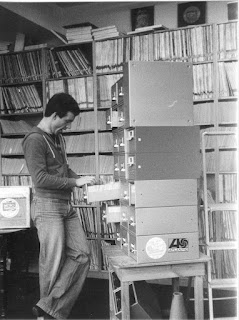

The many hours of off-air boredom were relieved by listening to previously unheard stations from Lebanon, Cyprus and Egypt. There was a television room on-deck where I would watch the afternoon post-war American movie of the day on Jordan TV. I would write letters to my thirteen-year-old sister back in the UK. I would read cover-to-cover all the English-language music magazines, including heavyweight weekly ‘Billboard’, that we received. I would comb the small record library and listen to previously unheard discs in the second production studio. Once the weather became calmer in the summer, it was an idyllic existence to live without day-to-day responsibilities. My hair grew longer than it had ever been, my skin turned dark brown and my body became even thinner as a result of seasickness and Radha’s meals.

The station’s Persian founder and owner, Abie Nathan, was a peace activist who had been making grand publicity-seeking gestures in Israel to promote his cause since the 1960’s. He bought the ship second-hand in 1973, allegedly with the financial assistance of John Lennon, and had installed the radio broadcasting equipment. However, after more than a decade continuously anchored a few kilometres off Tel Aviv, the ship and its facilities had seen better days by the time I arrived.

Like many station owners, Nathan was given to flights of fancy, calling up on ship-to-shore radio to demand airtime for content that interrupted our on-air routines. During my stint, Nathan hired a duo of British ‘radio consultants’ to improve the station. Their big idea was to split the station into two different services on FM and AM during certain dayparts, requiring both studios to be used simultaneously for live programmes. This proved not such a practical idea when the station was so regularly short-staffed. I was allocated the evening FM show, for which I used Steely Dan’s ‘FM’ track as theme music and selected soft rock songs. I was rewarded with a letter from a listener in Finland who had heard my show and sent me a cassette recording postmarked the following day to prove it (remember this was pre-internet).

If there was one lesson I learned from my six months at sea, it was the first occasion I had worked with self-styled ‘radio consultants’ who seemed to talk endlessly about their successes, obviously possessed the gift of the gab, but who were revealed as less knowledgeable than they might appear. In those pre-digital times, I was surprised to be the person on-board who was asked to explain which of a quarter-inch reel-to-reel tape machine’s three heads has to be used for marking up edits. In future years, I was to meet more ‘consultants’ who promised to deliver radio ‘success’ but who seemed to lack the requisite skills to achieve anything more than talking about it.

My experience presenting programmes for hours every day on-air confirmed my thinking that being a DJ was not my ambition in radio. I was told I possessed a good ‘radio voice’, I could operate the equipment and loved playing music, but I much preferred a production role in which I could contribute creatively beyond just opening my mouth. One of the most enjoyable programmes I created on ‘The Voice of Peace’ was a ‘special’ to mark the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Sharpeville Massacre with a selection of pertinent African and American music. I wish I had put a cassette in the studio tape machine to record it!

After having been denied shore leave during my first three months, I now had to endure an hour of bonking noises from the second bed on the other side of our small shared hotel room until the lady of the night slipped away, leaving the seaman to snore loudly until daylight. The hotel turfed us out during daytime, so I regularly retreated to the nearby White House café where office staff, hangers on and the station’s most loyal listeners would sit at a roadside patio table and chat ‘radio’. I came to love Tel Aviv during my total three weeks of shore leave … despite the ongoing war, the terrible economy and random acts of terrorism.

Once my six months were completed, I visited the station’s Tel Aviv office to collect my final wages. I reminded Abie Nathan that I had worked an additional three weeks beyond my contract as a result of having been denied shore leave during my first three months on board. Would he pay me an additional US$75? He adamantly refused. Unlike some of my DJ colleagues, I harboured no intention of returning for a further six-month stint. Rather, I never wanted to work or live on a ship again. Surely there must be a radio job I could secure that did not necessitate me being sick in a bucket after eating unidentifiable meals.

In 1993, I was working in East Europe when I read that the ‘Voice of Peace’ ship had been deliberately scuttled at sea by its owner after two decades’ broadcasts, the final day having comprised non-stop Beatles songs. I have never mustered the enthusiasm to attend subsequent ‘offshore radio’ nostalgia events but my experience of Israel left an indelible mark on me. Pass the halva!

[Originally published at https://peoplelikeyoudontworkinradio.blogspot.com/2023/06/my-life-as-seadog-1985-voice-of-peace.html]

![[my pyjama top, 1989 to 2023]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiLDjK2iX4MEh_i-sHJOqvXAZBavPsvPqMkyngG7EtJZ0HXlCNiB_twdyTFyDBnCeKX-HX5danhxM3gGb6XK1JReLm9DhI55O8qIF8fW8OxslXjxaZ7uWN9p_7xL5SikJpA4krxU6wjBRw8mpWEu6euFw6Ggj5fkvpppKW_lDmy2TJ7tYTcXkMGmmaN/w300-h400/AceRecords.jpg)