Click here for my latest presentation containing data for the UK commercial radio industry’s key performance metrics in Q1 2009 for revenues, audiences and radio receiver hardware.

Revenues

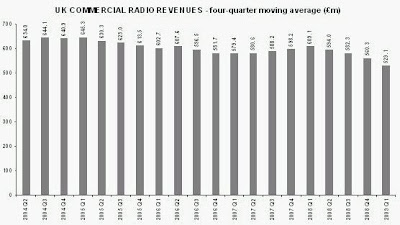

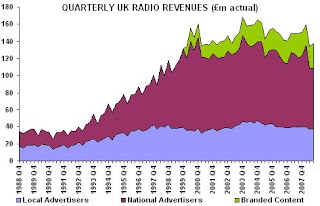

Q1 2009 radio revenues were down 19.5% year-on-year, eclipsing the previous quarter’s 14.5% decline (although Q1 2008 had been an exceptionally strong quarter). National advertising continues to weaken, the last four quarters having declined by 15.9%, 12.2%, 21.2% and 28.8% respectively year-on-year. By comparison, local revenues have proven more resilient, down 6.4% in Q1 2009 year-on-year.

The gravity of the downturn is demonstrated by the fact that Q1 2009 was the lowest quarter for revenues since 1999 (at face value – if inflation were factored, the situation would be worse). The size of the industry is likely to continue to contract throughout 2009 and it will have to make further, significant cuts to overheads simply to ensure its survival. Public and parliamentary debate to date has focused upon the economic plight of local newspapers, but local commercial radio is just as endangered.

John Myers’ local radio report for Digital Britain suggested a number of regulatory and legislative changes that would potentially ease the financial burden on the commercial radio sector, but these still remain proposals at present. Until the government’s Digital Britain final report and Ofcom’s consultation exercises potentially turn these recommendations into action, the worsening economic pressures on commercial radio are likely to continue to produce further casualties.

Although some voices are already talking up a future bounce back of revenues after the recession (whenever that might be), it is important to recognise that the recent advertising downturn has only exacerbated a downward trend in radio revenues that was already established. In real terms (removing the impact of inflation), radio revenues peaked in 2000 and had already declined by 25% between 2000 and 2008. The current economic cycle is merely aggravating the structural decline that was already evident.

Audiences

At the root of commercial radio’s structural problem is the public’s declining consumption of its output – hours listened during the last four quarters were down 2.3% year-on-year. Radio as a medium continues to attract significant amounts of listening (22.4 hours per week per listener) and reaches 90% of the population weekly. Within those impressive totals, commercial radio is maintaining most of its reach but is losing listener hours. In Q1 2009, the average commercial radio listener consumed 13.5 hours per week, compared with 15.6 hours per week five years earlier.

It would be easy to lay the blame for this loss of listening at the door of increasingly promiscuous 15-24 year olds spending increasing amounts of time using mobile phone applications, social networking websites and streamed video. Whilst it is true that 15-24 year olds’ average time spent with commercial radio has fallen to 12.4 hours per week in Q1 2009 from 15.2 hours per week eight years ago, blame must also be shouldered by the other constituent demographics within commercial radio’s ‘heartland’ 15-44 year old audience.

Reductions in time spent listening to commercial radio have been almost as substantial amongst 25-34 year olds (12.7 hours per week in Q1 2009, down from 15.5 hours eight years earlier) and 35-44 year olds (14.2 hours per week in Q1 2009, down from 16.6 hours eight years ago). Commercial radio’s share of listening amongst both these demographics fell to 49% in Q1 2009, so that BBC radio listening now dominates all age groups except for 15-24 year olds, in which commercial radio still has a 59% share. Only two quarters ago, commercial radio’s share had been above 50% in all three constituent demographics of its 15-44 ‘heartland’ audience whilst, back in 1999, it had been above 60% in all three. These changes represent the crux of commercial radio’s long-term problem.

Additionally, people under the age of 40 are evidently listening to more ‘audio’ then ever before, assisted by the take-up of portable audio players and the blossoming integration of audio applications into mobile phones. However, listening on these new platforms is not being reflected in the audience data quoted above because the RAJAR radio ratings metric continues to define ‘radio’ listening in the traditional linear way, excluding time-shifted consumption (listen again, podcasts) and non-broadcasters (Last.fm, Spotify). Sooner or later, the industry will have to decide whether RAJAR is to remain merely a marketing tool to demonstrate the two traditional broadcasters’ (BBC and commercial radio) continuing dominance of the shrinking market for linear radio; or whether it is more important for RAJAR to demonstrate that ‘audio’ is a growing consumer medium now shared amongst a widening group of content providers. Comments made recently by the BBC’s Tim Davie at the RadioCentre conference offer encouragement in this respect.

Transactions, Openings & Closures

In May 2009, Global Radio finally sold its eight Midlands stations (an OFT requirement of its acquisition of GCap Media) to former Chrysalis Radio chief executive Phil Riley in a deal reported to be worth £30m and backed by Lloyds TSB. Global’s rival Bauer Radio was long anticipated to be the successful buyer, causing some to comment that the transaction has the hallmarks of a ‘warehousing’ deal that would satisfy current competition issues until media ownership rules are amended by legislation to allow further radio consolidation and cross-ownership.

In May 2009, UKRD succeeded in its acquisition of The Local Radio Company [TLRC] in a deal that valued the latter at £2.88m. UKRD owned six local stations, having closed one and sold three stations during the last year. TLRC owned 20 stations, having sold eight during the last year. Since the acquisition, two further TLRC stations have been sold – Bournemouth’s Fire FM to Westward Broadcasting for £40,001, and Macclesfield’s Silk FM to neighbouring Dee 106.3 for a nominal amount. In the seven months to April 2009, Fire’s operating loss was £129k on revenues of £216k, implying an annual cost base of almost £600k, considerable for a station with a weekly reach of 28,000 adults.

In April 2009, TLRC also sold digital station Jazz FM for £1 to former TLRC chief executive Richard Wheatly and former finance director Alistair Mackenzie, the station having lost £733k in the six months to March 2009. In May 2009, the new owners announced a £500k national poster campaign for the station which broadcasts on Sky, Freesat and regional DAB multiplexes. To date, no digital radio station has generated an operating profit.

Forward Media finally exited the radio business by selling its last remaining stations, Connect FM in Kettering and Lite FM in Peterborough, to Adventure Radio (which owns Chelmsford Radio, Herts Mercury and Southend Radio) for undisclosed amounts.

In March 2009, Midwest Radio sold its two stations, MidWest Shaftesbury and MidWest Yeovil, to South West Radio Ltd, the company that had purchased five stations in the West Country from the administrators last year, following the failure of Laser Broadcasting. Another former Laser station, Fresh Radio in Skipton, was sold in March 2009 by administrators to Utopia Broadcasting which includes some station management.

In April 2009, CN Radio sold Touch FM in Banbury to a management buyout team for an undisclosed amount and the station was relaunched as Banbury Sound. In November 2008, CN had said it would close its Touch FM stations in both Banbury and Coventry if it did not find buyers.

April and May 2009 saw the closure of seven local analogue commercial stations, a greater number than in the previous three years. Ofcom revoked the licence of KCR FM in Knowsley from owner Polaris Media, following failure to comply with its format. Sunrise Radio closed two London stations, Time 106.8 in Thamesmead and South London Radio in Lewisham, which had been up for sale since last year. Pennine FM, purchased by John Harding from TLRC last year, closed in Huddersfield. UTV closed Valleys Radio in South Wales after Ofcom had rejected a co-location request. Jason Bryant closed Radio Hampshire in Southampton and Winchester, stations which he had acquired from Southampton Football Club in 2007 and from Tindle Radio in 2008 respectively.

However, Pennine FM has since been acquired from administration by former station staff Adam Smith and Steve Buck and relaunched in May 2009. Similarly, internet broadcaster Play Radio has expressed interest in acquiring the two Radio Hampshire stations from administration, and a creditors’ meeting is due on 24 June.

On digital platforms, local Stafford station Focal Radio closed in May 2009 with the loss of 23 jobs after local businessman Mo Chaudry, who had invested £80,000 to ‘save’ the station, withdrew his support after being arrested on corruption charges involving Stoke City Council. London DAB station Zee Radio (simulcast on Spectrum AM) closed in April 2009 after a year on-air.

The national DAB multiplex Digital One has three new additions, two temporary. On 20 April 2009, forces radio station BFBS launched a simulcast on the platform, following its earlier trial. On 1 June 2009, Amazing Radio launched a six-month trial service showcasing unsigned UK bands as an extension of its Amazing Tunes website. From 27 June 2009, Folder Media’s Fun Kids station will be simulcasting a 14-week trial, extending its present availability on DAB in London.

In London, black talk/music station Colourful Radio launched on DAB on 2 March 2009, and music station NME Radio added DAB on 13 May 2009.

In the coming months, UKRD/TLRC is likely to divest further local stations from its portfolio. At the top end of the commercial radio business, consolidation has created huge groups of large local stations whilst, at the bottom end of the market, an increasing number of small local stations are now being divested from groups to local owners (or closed down). In a small way, this is returning local commercial radio to its 1970s roots, when it was expected that each station would be owned by local entrepreneurs. It will be instructive to see how each of these divergent strategies succeeds in such tough economic times.