The current DAB radio transmission system in the UK is presently not robust enough to rival old fashioned, but more reliable, FM. All parties are agreed on that point. To get DAB up to FM standard, a huge amount of work needs to be done, which would cost a lot of money. How much money? Nobody seems to agree upon that point. Sums have been suggested in Parliamentary debates and in reports that vary wildly.

What information is in the public domain about the costs of DAB transmission? In the UK, not a lot. The BBC owns one of the two national DAB radio multiplexes, for which only a small amount of data about costs has been published.

By 2011, the BBC national DAB multiplex will cover 90% of the population at an estimated transmission cost of £11m per annum. The technical challenge of DAB is that you need more additional transmitters than FM (because of DAB’s characteristics) to improve coverage. To achieve 95% population coverage increases the cost of DAB to £38m per annum (the BBC said in 2008). To achieve 99% coverage increases the cost to £40m per annum (the BBC said in 2007).

Compared to the existing FM transmission system (which the BBC said in 2007 offered around 99% population coverage), DAB will be more expensive. Not at present, because DAB is only covering 86% of the population, but increasing that percentage to the same as FM will be costly for DAB. Very costly. By comparison, the existing national FM transmission network had cost the BBC £12m in 2007. This should have reduced to £10m in 2009 after transmission contractor Arqiva agreed to discount its existing contracts (following its acquisition of rival NGW). The same discount may have lowered the cost of existing DAB transmission agreements, but not of future contracts for build-out to 99% coverage.

The BBC broadcasts only four national stations on FM whereas, on DAB, it broadcasts more channels. How many more? The number of BBC stations on DAB varies because one station is part-time and because two full-time stations are proposed for closure next year. To take an example of a music station using 128kbps of DAB bandwidth, it would cost £1.6m per annum to cover 90% of the population, £5.6m to cover 95% and £5.9m to cover 99%. Compare that to a national FM station that currently costs the BBC £2.6m per annum. It seems that DAB may be cheaper at present, but is certainly not cheaper once it is required to achieve equivalent FM coverage.

The second national DAB multiplex in the UK is owned by Arqiva (formerly ‘Digital One’) and covers 90% of the population. Does it publish a price list for commercial customers wanting DAB carriage? Seemingly not. However, in September 2009, Premier Christian Radio had said it was paying £650,000 per annum for national DAB carriage, using 64kbps of spectrum. The pro rata cost for a 128kbps music station would be £1.3m per annum, close to the previously estimated BBC cost for population coverage of 90%. Arqiva says it “is working on a transmitter roll out plan to further extend coverage,” having added four new transmitter sites in 2009.

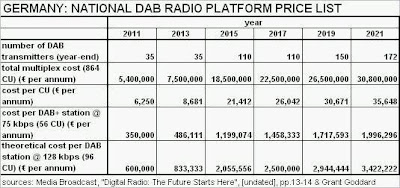

In Germany, the transmission provider, Media Broadcast, has published a price list for commercial stations interested in broadcasting on its planned DAB platform. It anticipates that German stations will use the more spectrum efficient DAB+ system, whereas the UK is wedded to the older DAB system. The prices quoted below (in Euros) require a radio station to take a minimum 10-year contract and are based on two multiplexes operating at each transmitter location (if that were not to happen, the costs would be higher).

By 2015, Media Broadcast anticipates that its 110 DAB transmitters will provide coverage to 78% of the population indoors and 92% of the population outdoors. There seems to be no commitment in Germany for DAB to achieve the 95% to 99% population coverage that is planned in the UK. Nevertheless, the transmission cost of a (hypothetical) DAB station using 128kbps would be as high as E3.4m (£2.8m) per annum by 2021. As in the UK, the cost escalates rapidly as the DAB network is built out to reach more of the German population. Whereas, in 2011, the initial E0.6m (£0.5m) per annum might not seem prohibitive to cover a country that has a third larger population than the UK, that annual cost is multiplied six-fold by the end of the 10-year contract.

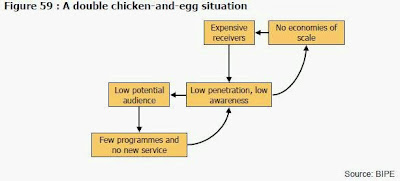

In both the UK and Germany, the cost of DAB roll-out to ensure that reception is as robust as FM will add significantly to the platform’s costs. Without this roll-out, DAB can never replace FM, and the burdensome cost of simulcasting on both DAB and FM will continue. With this roll-out, DAB seems to end up costing more than FM to achieve similar coverage. So what is the point?

In the UK, neither Ofcom nor the government’s DCMS department have published analyses of the costs of DAB roll-out. Their pursuit of the DAB platform has had absolutely nothing to do with the real world economics of the UK radio industry. Their numerous published reports and consultations deal with a virtual reality of the radio industry that exists solely in their minds, perhaps a reflection of the fact that none of them have ever worked in the radio sector they try to regulate.

Ofcom’s plans for upgrading DAB, to be published imminently, merely prolong the regulator’s fantasy that the DAB platform is ‘the future of radio’. Ofcom’s apparent determination to run the radio industry into the ground economically through its insistence upon implementing a misguided ‘digital strategy’ for the sector has already proven a disaster, helping reduce the commercial sector’s profitability to nil. Even more disastrous is the radio industry’s seeming inability to confront Ofcom collectively, to insist that ‘enough is enough’, and to demand that Ofcom goes back to the drawing board in its whole strategy for radio’s future.

How can Ofcom retain an ounce of credibility when it had forecasted publicly (as recently as November 2006) that digital platforms would account for 42% of all radio listening by year-end 2009? The actual figure was 21%. As a result, all those radio operators who had based their business plans for digital radio upon Ofcom’s ‘professional’ forecast have faced financial ruin. Instead of reaching for the tissue box, these businesses should be reaching for their lawyer.

Practical action is what is needed now, not yet another Ofcom fantasy plan for radio’s DAB future.