31 March 1990 was the memorable day when London‘s first licensed black music station, Choice 96.9 FM, arrived on-air. Until then, the availability of black music on legal radio had been limited to a handful of specialist music shows, even though about half of the singles sales chart was filled with black music. The decision by then regulator the Independent Broadcasting Authority [IBA] to license a London black music station was part of a huge government ‘carrot and stick’ campaign to rid the country of pirate radio. On the one hand, new draconian laws had been introduced that made it a criminal offence even to wear a pirate radio T-shirt or display a pirate radio car sticker. On the other hand, the establishment knew that some kind of olive branch had to be offered to the pirate stations and their large, loyal listenership.

Many pirate stations, having voluntarily closed down in the hope of becoming legitimate, were incensed when the IBA instead selected Choice FM for the new South London FM license. Its backers had no previous experience in the London pirate radio business, but had previously published ‘Root’ magazine for the black community in the 1970s. Although it was impossible for one station to fill the gap left by the many pirates, Choice FM tried very hard to create a format that combined soul and reggae music with news for South London’s black community, which was precisely what its licence required. The station attracted a growing listenership and it brought a significant new audience to commercial radio that had hitherto been ignored by established stations. With Choice FM, the regulator succeeded in fulfilling two aspects of public broadcasting policy: widening the choice of stations available to the public; and filling gaps in the market for content that only pirate radio had supplied until then.

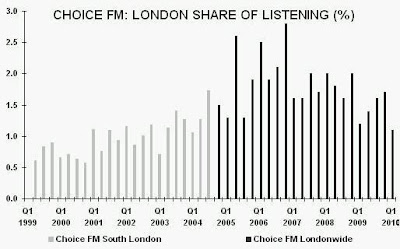

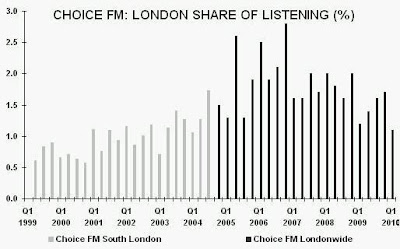

In 2000, Choice FM won a further licence to cover North London with an additional transmitter. For the first time, the station was now properly audible across the whole capital and had access to more listeners and more potential advertising revenues. Its listening doubled and, at its peak in 2006, Choice FM achieved a 2.8% share, placing it ahead of TalkSport and BBC London in the capital. Choice FM had no direct competitor in London, although indirectly some of its music had always overlapped Kiss FM. The station’s future looked rosy.

However, the Choice FM shareholders must have realised just how much their little South London station was worth, at a time when commercial radio licences were being acquired at inflated prices. Already, in 1995, Choice FM shareholders had won a second licence in Birmingham, but had then sold the station in 1998 for £6m to the Chrysalis Radio group, who turned it into another local outlet for its network dance music station Galaxy FM. At a stroke, the black community in Birmingham had lost a station that the regulator had awarded to serve them. Black radio in Birmingham was dead. The die was cast.

The then regulator, the Radio Authority, had rubber-stamped this acquisition, stating that it would not operate against the public interest. The Authority requested some token assurances: at least one Afro-Caribbean member on the station’s board; an academy for training young people, especially from the black community, in radio skills; and market research about the impact of the format change on the black community. None of these made any difference to what came out the loudspeaker. Birmingham’s black community was sold down the river.

Changes in UK media ownership rules were on the horizon that would soon allow commercial radio groups to own many more stations within a local market. As a result, in 2001, the UK’s then largest radio group, Capital Radio plc, acquired 19% of Choice FM’s London station for £3.3m with an option to acquire the rest. In 2003, it bought the remaining 81% for £11.7m in shares, valuing the London station at £14.4m. The Choice FM shareholders had cashed in their chips over a five-year period and had generated £21m from three radio licences. What would happen to Choice FM London now?

Graham Bryce, managing director of Capital Radio’s London rock station Xfm (which Capital had acquired in 1998 for £12.6m), said then:

“Our vision is to build Choice into London’s leading urban music station, becoming the number one choice for young urban Londoners. Longer term, we intend to fully exploit the use of digital technology to build Choice nationally into the UK’s leading urban music station and the number one urban music brand.”

Capital Radio and subsequent owners seemed to want to turn Choice FM into a station that competed directly with Kiss FM (owned by rival EMAP). But they never seemed to understand that Kiss FM was now a ‘dance/pop’ station, whereas Choice FM had always been firmly rooted in the black music tradition of soul, reggae and R&B. Such semantics seemed to be lost on Choice FM’s new owners and on the regulator, but certainly not on Choice FM’s listeners, who had no interest in Kylie Minogue songs.

In 2004, Capital Radio moved Choice FM out of its South London base and into its London headquarters in Leicester Square. The station’s final link with the black community of South London it had been licensed to serve was discarded. In 2005, Capital Radio merged with another radio group, GWR plc, to form GCap Media plc. In March 2008, Global Radio bought GCap Media for £375m. In July 2008, Choice FM managing director Ivor Etienne was suddenly made redundant. One of the station’s former founder shareholders commented:

“I’m disappointed that the new management decided to relieve Ivor Etienne so quickly. My concern is that I hope they will be able to keep the station to serve the community that it was originally licensed for.”

However, from this point forwards, it was obvious that new owner Global Radio had no interest in developing Choice FM as one of its key radio brands. In the most recent quarter, the station’s share of listening fell to an all-time low of 1.1% (since its audience has been measured Londonwide). Sadly, the station is now a shadow of its former self, even though it holds the only black music commercial radio licence in London (BBC digital black music station 1Xtra has failed to dent the London market, with only a 0.3% share).

This week, news emerged from Choice FM that its reggae programmes, which have been broadcast during weekday evenings since the station opened, will be rescheduled to the middle of the night (literally). One of the UK’s foremost reggae DJs, Daddy Ernie, who has presented on Choice FM since its first day, will be relegated to the graveyard hours when nobody is listening. From 2003, after the Capital Radio takeover, reggae songs have been banished from the 0700 to 1900 daytime shows on Choice FM. Now the specialist shows will be removed from evenings, despite London being a world centre for reggae and having more reggae music shops than Jamaica.

Station owner Global Radio responded to criticism of these changes in The Voice newspaper: “Choice [FM] has introduced a summer schedule which sees various changes to the station including the movement of some of our specialist shows.”

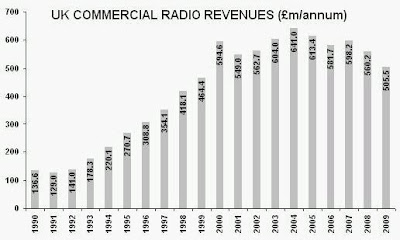

Once again, the regulator will roll over obligingly and rubber-stamp these changes. For Global Radio, the endgame must be to transform the standalone Choice FM station into a London outlet for its Galaxy FM network. At present, London-based advertisers and agencies can only listen to Galaxy on DAB or via the internet. A London Galaxy station on FM would bring in more revenue for the brand as a result of more listening hours and its higher profile in the advertising community. It would also provide a direct competitor to Kiss FM London (ironic, because Galaxy FM had been launched in 1990 by an established commercial radio group as an out-of-London imitation of successful, London-only Kiss FM). Global Radio’s argument to persuade the regulator will probably be that Choice FM’s audience has fallen to uneconomic levels. And whose fault was that?

Already, Global Radio’s website tells us that “Choice FM is also included as part of the Galaxy network” which “consists of evolving mainstream music supported by entertaining and relatable presenters.” And yet, according to Ofcom, Choice FM’s licence is still for “a targeted music, news and information service primarily for listeners of African and Afro-Caribbean origin in the Brixton area but with cross-over appeal to other listeners who appreciate urban contemporary black music.” How can both these assertions be true of a single station?

For the black community in London, and for fans of black music, this will be the final straw. Just as happened in Birmingham, the new owner and the regulator will have collectively sold Choice FM’s listeners down the river. Another station that used to broadcast unique content for a unique audience will have been wilfully destroyed in order to make it almost the same as an existing station, playing almost the same content. We have many commercial radio stations, but less and less diversity in the music they play. Radio regulation has failed us.

For Choice FM, the writing was on the wall in 2003 when Capital Radio bought the station and one (unidentified) former DJ commented:

“Choice [FM] was there for a reason [to be a black music station for black people], but that reason changed [since] 13 years ago. That’s why you’ve got over 30 pirate stations in London. If Choice FM kept to the reason why they started, you wouldn’t need all them stations. But Choice has become a commercial marketplace. They’ve sold the station out and they should just say they’ve sold the station out. What’s wrong with that? They have sold the station that was set up for the black community and they know they’ve done the black community wrong. But they’ve made some money and they’ve sold it. Why not let your listeners know?”

For me personally, as a black music fan and having listened to Daddy Ernie for twenty years, I am much saddened. In the 1970s and 80s, I had found little on the radio that interested me musically, so I listened to pirate stations and my own records. During those two decades, I actively campaigned for a wider range of radio stations to be licensed in the UK and, by the 1990s, I had played a direct role in making that expansion of new radio services happen successfully. Where did it get us? Now, years later, I have gone back to listening mostly to pirate radio and my own records (and internet radio). I am sure I am not the only one.

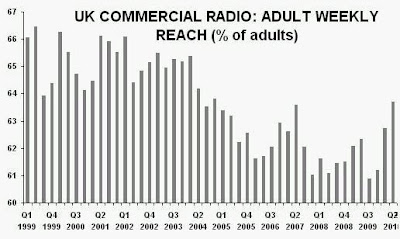

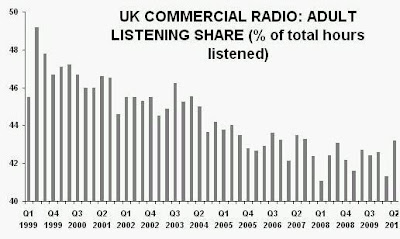

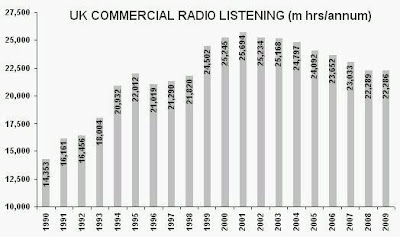

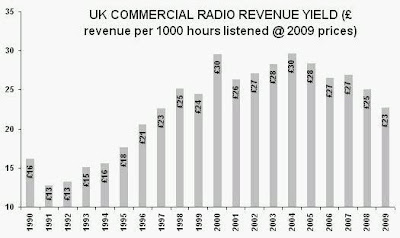

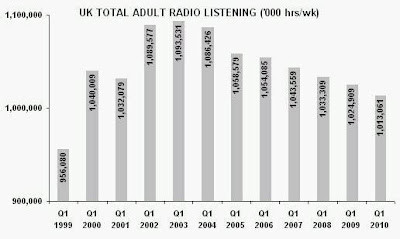

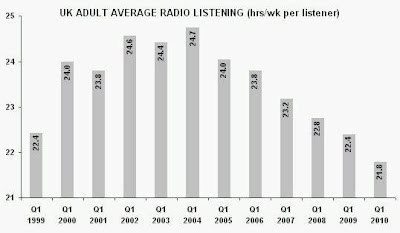

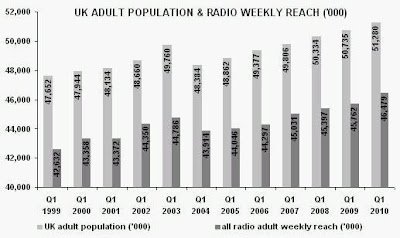

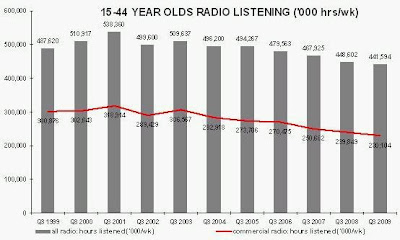

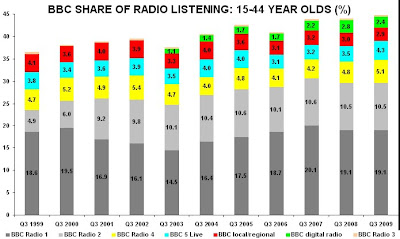

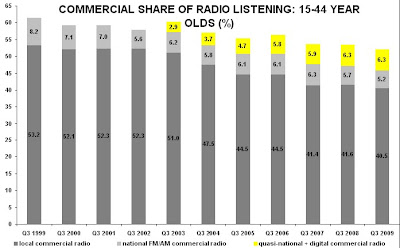

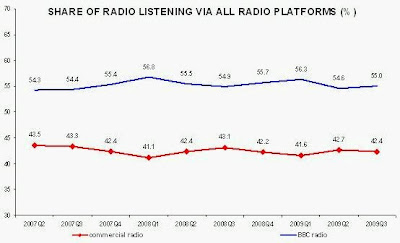

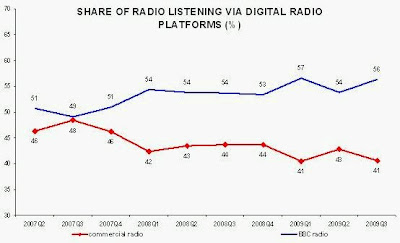

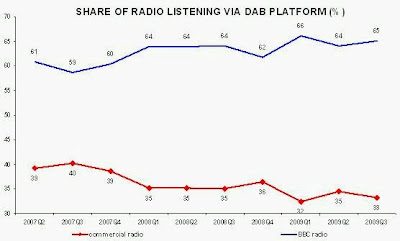

The radio industry and the regulator seem not to understand one important reason why radio listening and revenues have been declining for most of the last decade. They need to examine how, through their decisions, they have consistently sold down the river their station audiences and the very citizens whom their radio licenses were specifically meant to serve. Listeners vote with their ‘off’ buttons when station owners renege on their licence promises and the regulator lets them. Choice FM is sadly just one example.

In 2006, a lone enlightened Ofcom officer, Robert Thelen-Bartholomew, had asked at a radio conference:

“Is there room to bring the content of illegal stations into the fold? One way or another, whether we like it or not, we have a large population out there listening to illegal radio. Why do they listen? We are trying to find out. But, if you listen to the stations, they are producing slightly different content and output [from licensed stations]. Some of it is very high quality. Some of it is very interesting. So, what options are there for bringing some of that content into mainstream radio?”

Seemingly, none. The last FM commercial radio licence the regulator offered in London was more than a decade ago. Last year, when two small South London FM stations (one licensed for a black music format) were closed by their owner, the regulator unilaterally decided not to re-advertise their commercial radio licences (see the story here). A pirate radio station has not been awarded a commercial radio licence by the regulator for two decades.

Why do pirate radio stations still exist? Because, just as in the 1970s and 1980s, there are huge gaps in the market for radio content that – in spite of BBC radio, commercial radio and their regulators – remain unfilled. It is no coincidence that the share of listening to ‘other’ radio stations (i.e. not BBC radio and not commercial radio) in London is near its all-time high at 3.1%.

Farewell, Choice FM. I knew you well for twenty years.

And, irony of ironies, we are in Black Music Month.

[thanks to Sharleen Anderson]