Andy Parfitt’s departure from the station controller job at BBC Radio 1 after thirteen years marks a significant event for the UK radio sector. Parfitt’s accomplishments during his tenure were many, but did not extend to significantly turning around the station’s audience ratings.

At the time Parfitt took on the controller job in March 1998 at Radio 1:

• its share of listening was 9.4%, compared to 8.7% in Q1 2011

• its adult weekly reach was 20%, compared to 23% in Q1 2011

• its average hours per listener per week were 8.1, compared to 7.8 in Q1 2011.

One metric did demonstrate a healthy increase – Radio 1’s absolute weekly reach was up from 9.7m adults in Q1 1998 to 11.8m in Q1 2011. However, part of that increase is attributable to the UK adult population having grown by 9% in the interim. Certainly, more adults listen to Radio 1 now than in 1998, but for shorter periods of time, and so the station’s share of total radio listening has declined.

Given this impasse to the improvement of Radio 1’s ratings, I was surprised to read in the BBC press release announcing Parfitt’s departure that:

“Appointed Controller, BBC Radio 1, in March 1998, Andy has led Radio 1 and 1Xtra to record audience figures …”

… and surprised to read Parfitt’s boss, Tim Davie, declaring that:

“Andy has been a fantastic Controller and leaves Radio 1 in rude health – with distinctive, high quality programmes and record listening figures …”

The one person still working at Radio 1 who should know for sure that “record audience figures” had not been achieved during the last quarter, last year, the last decade or during Parfitt’s entire tenure is Andy Parfitt. Why? Because, between 1993 and 1998, Parfitt had been chief assistant to then Radio 1 controller Matthew Bannister, a turbulent period during which the station’s audience was decimated by a misguided set of programme policies that failed miserably to connect with listeners.

Between the end of 1992 and March 1998, when Parfitt took over from Bannister (whom the BBC had promoted to director of radio), Radio 1’s:

• share of listening fell from 22.4% to 9.4%

• adult weekly reach fell from 36% to 20%

• average hours listened per week fell from 11.8 to 8.1

• absolute adult reach fell from 16.6m to 9.7m.

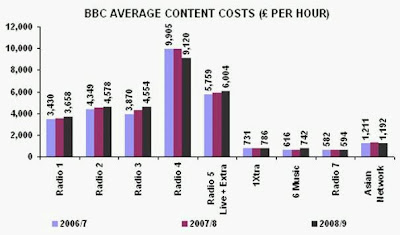

Radio 1 lost an incredible 58% of its listening, and 7m listeners, within that five-year period, a calamitous disaster from which the station has never recovered [see graph above]. Since then, Parfitt has kept the ship relatively steady, having been appointed in 1998 as a safe pair of BBC hands for Radio 1 after the tragedy of Bannister (who had come from Capital Radio via BBC GLR and had a fantastic track record in news radio, but not in music radio).

Never again will Radio 1 achieve a weekly audience of 17 million adults, as it had done in 1992. Those days are long gone. In recent years, fewer young people are listening to broadcast radio, and they are listening for shorter periods of time. Sadly, radio does not prove as exciting for them as the internet, games or social networking.

Of course, it would have been nice for any incumbent to leave the Radio 1 job on a ‘high.’ But, unfortunately, it was never going to happen with Parfitt, or probably with any successor. Radio 1’s ‘golden age’ was wilfully destroyed twenty years ago. Nevertheless, somewhere, somebody in the BBC must have decided to invoke the notion of Parfitt’s “record audience figures,” regardless or not of whether they were a fact.

What surprises me is that every BBC press release must have to pass through endless approvals – within the originating department, in the press office and in the lawyers’ office – before it reaches the public. Did nobody out of the dozens of people that must have checked this particular press release ask the simple question: can you substantiate this “record audience figures” claim?

RAJAR radio audience data are publicly available for all to see. Anyone from the BBC could have checked and found that, using every radio listening metric known to man, Radio 1’s “record audience figures” were all achieved two decades ago, rather than at any time during Parfitt’s tenure. Maybe they didn’t check. Or maybe they did, but pressed ahead anyway.

The ability to play fast and loose with numbers and statistics, particularly those that can be said to be at an ‘all time high,’ might appear to be endemic within the UK radio industry. I have highlighted similar instances of the industry’s abuse of statistics in other claims. Now that the consumer press only seems interested in ‘radio’ stories involving celebrities, and now that the media trade press has been reduced to recycling radio press releases, ‘myth’ can quite easily be propagated as ‘fact.’

I am reminded of a passage in my new book about KISS FM when, two decades ago, I had asked my station boss why an Evening Standard profile of him and his car had featured a vehicle that was not the one he owned or drove.

“It seemed to make a better story,” he told me.