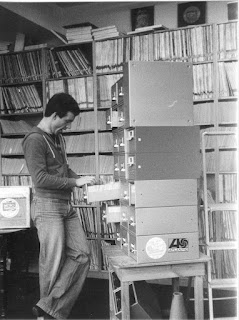

“I’m SO sorry,” I grovelled to the petite musician on whose foot I had just accidentally trodden. We were stood side-by-side in the record library – my ‘office’ – of local commercial station ‘Metro Radio’ in Newcastle. Kate Bush was kindly autographing several copies of the new album she was visiting to promote, which were about to be awarded as competition prizes to listeners. She had just been interviewed live on-air by one of the station’s daytime presenters and was soon to be whisked away by car to visit yet another local station somewhere across the country.

I had been basking in a brief moment of hit-picking glory, feted by Bush’s record company ‘EMI Records’ for having simultaneously added two singles by singer Sheena Easton (‘Modern Girl’ and ‘9 to 5’) to the station’s ‘current hits’ playlist, the shortest list of any UK station following my radical overhaul of its music policy, guaranteeing substantial airplay for the label’s newest rising star. Relationships with record companies were always a rollercoaster ride. Months later, after I had refused to add Queen’s ‘Flash’ single to the playlist, on the grounds that it sounded more an advertising jingle than a proper song, EMI declined to offer further artist interviews and stopped supplying the station with its new releases altogether (requiring me to drive to the nearest record shop with a weekly shopping list). Bribery, blackmail and boycotts were widespread music industry practices.

After having first heard Bush’s debut single ‘Wuthering Heights’ on John Peel’s evening ‘BBC Radio One’ show two years previously, I had loved her 1978 debut album ‘The Kick Inside’ for its clever arrangements of smart songs with unexpectedly frank subject matter. I had considered the same year’s follow-up ‘Lionheart’ rather insubstantial comparatively and over-theatrical. After a two-year wait, the next album ‘Never For Ever’ was a return to form with a more diverse song list and extensive use of brand-new Fairlight sampler technology invented in 1979. Bush had visited ‘Metro Radio’ to promote this album’s release in September, after three singles extracted from it (‘Breathing’, ‘Babooshka’ and ‘Army Dreamers’) had already reached 16, 5 and 16 respectively in the UK charts.

After a further two-year wait, fourth album ‘The Dreaming’ was a revelation with songs referencing even more startling subject matter, produced in a dense soundscape that was the aural equivalent of Brion Gysin’s and William S Burroughs’ ‘cut-up’ techniques, interlacing samples, sound effects and dialogue from the Fairlight (think 1973’s analogue ‘The Dark Side Of The Moon’ on digital steroids). I have always been intrigued by its track ‘Suspended in Gaffa’ as an incredibly outspoken criticism of EMI Records on an album released by … EMI.

This was by no means the first occasion that musicians had criticised their record company within their recordings. During the 1970’s, I recall several reggae artists obliquely criticising Jamaican producer Joe Gibbs for his sharp ‘business practices’ (eventually Gibbs’ business was bankrupted after prosecution in the US for stealing songwriter royalties). Closer to home, reggae DJ ‘Prince Far I’ criticised British company ‘Charisma Records’ explicitly in his track ‘Charisma’ (credited to collective ‘Singers & Players’) after his 1981 deal to release three albums (‘Showcase In A Suitcase’, ‘Sign Of The Star’ and ‘Livity’) on its ‘PRE’ label had been soured by negligible sales. Part of its lyrics were:

“I see no idea in your place, Charisma. […] Wipe them out, Jah!”

Prince Far I also made a recording to criticise Britain’s ‘Virgin Records’ which had released three of his albums (‘Message From The King’, ‘Long Life’ and ‘Cry Tuff Dub Encounter Part 2’ in 1978-1979 on its ‘Frontline’ label), but which had then rejected a further finished album he had delivered. In a track inevitably entitled ‘Virgin’, he rapped:

“You call yourself [Richard, Virgin co-founder] Branson but I know that Branson is a pickle with no place on my plate. You call yourself [Simon, co-founder] Draper but I know draper is known to cover human bodies. You see ‘Frontline’, I see barbed wire. Opportunity to make big money. Irie, Jumbo [Vanreren, Frontline A&R manager]. I won’t forget you take the master tape and hang it up on your shelf. Music has no place in a gallery.”

This ‘lost’ album was finally released in 1998 [Pressure Sounds PSLP18], long after Prince Far I (and his wife) had been tragically murdered in Jamaica in a 1983 house break-in. In 1992, Virgin Records was acquired for a reported £560m by EMI Records which, returning to our story, had signed sixteen-year-old Kate Bush in 1975 to a four-year contract after hearing her three-song demo tape, paying a £3,000 advance. In 1976, Bush created her own company, Novercia Limited (Latin for ‘she who is new’), that she and her family alone controlled in order to manage her career and maintain the copyrights in her recordings and songs.

From the initial contract’s expiry in July 1979, Bush could finally renegotiate a replacement EMI contract which would allow Novercia to retain the copyright (instead of EMI) and henceforth lease her recordings to EMI for release. At that time, it was unusual for such a young artist to insist upon taking control of their career from their record company, particularly when it was as globally huge as EMI. Bush no longer wanted to be contractually required to do promotional tours, such as her visit to Metro Radio, and she was insisting upon complete artistic control. I imagine that these negotiations between opposing lawyers sat around expansive tables in bare conference rooms on an upper floor of EMI headquarters in Manchester Square (immortalised on The Beatles’ 1963 debut album cover photo) must have been tense and lengthy, particularly for twenty-one-year-old Bush.

Not only would these contractual back-and-forth’s have delayed the release of new recordings, but the inordinate time they must have consumed would have eaten into Bush’s ability to compose and record. During this period, Bush’s musical creativity would frustratingly have been put on hold by the ‘red tape’ of legal negotiations, alluded to in the song’s title (‘gaffa’ being a reference to ‘gaffer tape’, the all-important ‘WD40’-like fix-all of musicians in studios and on tour). At the same time, EMI was demanding to hear proof of Bush’s new material to ensure it was sufficiently commercially marketable to guarantee another ‘hit’ single. Her song ‘Suspended in Gaffa’ starts:

“They’ve told us that, unless we can prove that we’re doing it, we can’t have it all. EMI want it all.”

Except that the ‘E’ from ‘EMI’ must have been removed from the mix, either upon EMI lawyers’ insistence or upon the recommendation of Bush’s legal team. Only once you re-imagine that ‘E’ does the song make perfect sense in terms of record label/artist contractual disputes. The role of Bush’s lawyer in the negotiations is referred to:

“He’s gonna wrangle a way to get out of it [the initial EMI contract that had included renewal options].”

The impact of the tedious negotiations upon Bush’s creativity and the impatient EMI’s demands to hear her new songs are referenced in the chorus:

“Suddenly my feet are feet of mud. It all goes slo-mo [slow motion]. I don’t know why I’m crying. Am I suspended in gaffa [caught up in ‘red tape’]? Not ‘til I’m ready for you [EMI] can you have it all [my new recordings].”

EMI (then) managing director Bob Mercer later confirmed that Bush had burst into tears during their business meetings. The record company’s patronising response to her demands is referred to in the lines:

“… that girl in the mirror. Between you and me, she don’t stand a chance of getting anywhere at all. Not anywhere. No, not a thing. She can’t have it all.”

If Bush had not successfully agreed a new contract with EMI, it might have been threatening that she would be jeopardising her future success. I had witnessed the blackmail tactics of EMI in my job at Metro Radio. The significance of concluding these negotiations successfully was imperative for Bush, and she noted the impact it would have on her finally taking total control of her destiny:

“Mother, where are the angels? I’m scared of the changes.” (Bush’s mother appears briefly in the video, comforting her.)

The key to understanding the song’s theme is to recognise that the most telltale line “EMI want it all” was sung eleven times. Record companies almost inevitably want to have their cake and eat it simultaneously, regardless of the fallout for their own artists. Why else would EMI have refused to send its new record releases to Metro Radio if it was not prepared to cut off its nose to spite its face?

If all this speculation sounds farfetched, you have to ask why EMI was happy to license ‘Suspended in Gaffa’ to its partners for release as a single in European countries, but did not similarly release the song as a single in the UK? Would its London executives want to hear a track played on the radio every day that they knew obliquely criticised their own business strategies? As a result, this excellent song languished as a little played album track in Bush’s homeland. Perhaps that was the company men’s notion of ‘revenge’.

At the time of its release in 1982, I was barely watching television so had missed the video for this song, written and directed by Bush herself. Viewing it more than forty years later, I hoped to find hidden references to ‘EMI’ in the visuals. It looks as if Bush (“wearing a designer straightjacket,” interjected my wife) has been kidnapped and locked in a boarded-up wooden shed alongside huge chains and large wheels of (the music?) industry. Outside a huge (legal?) storm is blowing, from which she cannot escape, despite kicking up dust but running nowhere. Is that what it felt like to be under contract to EMI? Bush was always far too subtle to provide explicit messaging that would explain her songs. Perhaps I am missing something she communicates via her animated hand movements? In one brief section of the video, wrists apparently bound in gaffer tape, Bush tumbles head-over-heals through the vacuum of galactic space, maybe a visualisation of her feelings in the midst of lengthy legal wranglings. Prior to that, the video portrays her ‘head in the clouds’, perhaps how she had sensed her initial teenage success with EMI.

As I discovered from my own job at Metro Radio, EMI want it all. Perhaps that is why I felt I understood Bush’s message within ‘Suspended in Gaffa’ from my first listen. It remains a truly remarkable song.

[Originally published at https://peoplelikeyoudontworkinradio.blogspot.com/2024/04/stoking-star-maker-machinery-behind.html ]