Help seemed to have arrived for those consumers who are confused by the contradictory messages they are receiving about DAB radio, digital switchover and the future of FM/AM radio. The government created a ‘hot topic’ web page that addresses these issues in the form of a ‘FAQ’. Does it help clarify things?

The government FAQ states:

• “We support 2015 as a target date for digital radio switchover” but, in the next sentence, it says that 2015 is “not the date for digital radio switchover”

• “FM will not be ‘switched off’ … and will continue for as long as it is needed and viable” but then it fails to explain the reason the government is calling it ‘switchover’

• “We believe digital radio has the potential to offer far greater choice and content to listeners” but then it asserts that “quite simply the listener is at the heart of this [switchover] process”

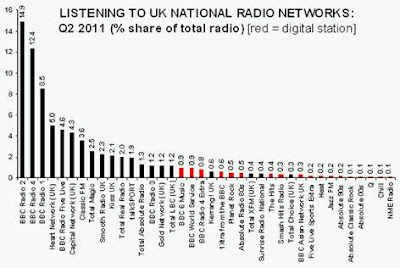

• “11 million DAB sets [have] already [been] sold” but, in the next sentence, it deliberately confuses ‘DAB radio’ with ‘digital radio’ which, it states, “accounts for around a quarter of all radio listening” [DAB accounts for only 16% of all radio listening]

• “Car manufacturers have committed to fit DAB as standard in all new cars by 2013” but it does not explain that only 1% of cars currently have DAB radio

• “Some parts of the country are not served well by DAB” but it then admits that “switchover can only occur when DAB coverage matches [existing] FM [coverage].”

Well, that makes everything crystal clear now. Switchover is not switchover. 2015 is the date but is not the date. It is the government that is insisting upon digital ‘switchover’ but it is a consumer-led process. Almost no cars have DAB now but, in 2+ years’ time, magically they all will. In parts of the UK, DAB reception is rubbish or non-existent, but ‘switchover’ will not happen until somebody spends even more money to make DAB coverage as good as FM … even though FM is already serving consumers perfectly well.

Sorry, what was the point of DAB?

While the UK government ties itself in increasingly tighter knots trying to explain the unexplainable, and to justify the unjustifiable, most of the rest of the world carries on regardless, inhabiting reality rather than a fictional radio future. In May 2010, a meeting in St Petersburg of the European Conference of Postal & Telecommunications Administrations considered the future usage of the FM radio waveband [which it refers to as ‘Band II’] in Europe. Its report stated:

“Band II is currently the de facto analogue radio broadcasting band, due to its excellent combination of coverage, quality and low cost nature both in terms of current networks available and receivers in the market. It is well suited to local, regional and national programming and has been successfully used for over forty years now. FM receivers are part of our daily lives and millions of them populate our households. FM radios are cheap to manufacture and for the car industry FM still represents the most important medium for audio entertainment.”

Its report concluded that:

• “Band II is heavily used in all European countries

• For the current situation the FM services are still considered as satisfactory from the point of sound quality but the lack of frequencies hinders further development

• There are no wide-spread plans or strategies for the introduction of digital broadcasting in Band II

• No defined final switch-off dates are given so far.”

Two paragraphs in the 28-page report seemed to sum up the present UK situation:

“The FM band’s ability to provide high-quality stereo audio, the extremely high levels of receiver penetration and the relative scarcity of spectrum in the band combine to make this frequency band extremely valuable for broadcasters.”

“As FM in Band II is currently, and for the foreseeable future, the broadcasting system supporting the only viable business model for radio (free-to-air) in most European countries, no universal switch-off date for analogue services in Band II can be considered.”

In the UK, we have just seen how “extremely valuable” FM radio licences still are to their owners. Global Radio was prepared to promise DAB heaven and earth to Lord Carter to ensure that a clause guaranteeing automatic renewal of its national Classic FM licence was inserted into the Digital Economy Act 2010. It got what it wanted and therefore avoided a public auction of this licence. Then, when expected to demonstrate its faith in the DAB platform, Global sold off its majority shareholding in the national DAB licence and all its wholly-owned local DAB licences.

Now the boot is on the other foot. Having succeeded in persuading the government to change primary legislation to let it keep commercial radio’s most valuable FM licence for a further seven years, Global Radio has now had to argue to Ofcom that analogue licences will become almost worthless in radio’s digital future. Why? In order to minimise the future Ofcom fee for its Classic FM licence. The duplicity is breathtaking.

When it last reviewed its fee for the Classic FM licence in 2006, Ofcom reduced the price massively because, it explained, it took

“the view that the growth of digital forms of distribution meant that the value associated with what was considered to be the principal right attached to the licence – the privileged access to scarce analogue spectrum – was in decline.”

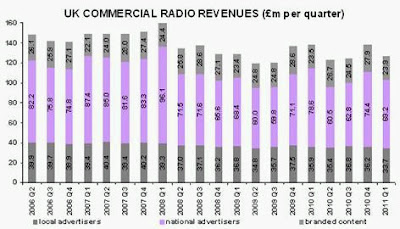

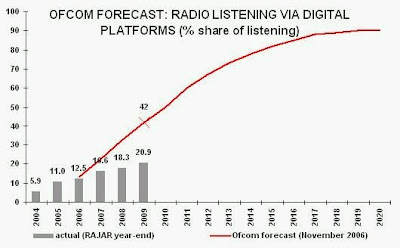

In 2006, Ofcom had published a forecast for the growth of digital radio platforms which has since proven to have been wildly over-optimistic. It had predicted that 42% of listening would be digital by year-end 2009, whereas the outcome was 21%. In 2006, as a result of the steep decline it was forecasting in analogue radio’s usage, Ofcom reduced the cost of Classic FM’s licence fee by 95% from £1,000,000 to £50,000 per annum (an additional levy on the station’s revenues was also reduced from 14% to 6% per annum). The losers were UK taxpayers – the licence fees collected by Ofcom are remitted to the Treasury. The winners were Classic FM’s shareholders, who were gifted a cash cow by Ofcom bureaucrats who misunderstood the radio market.

Fast forward to 2010, and Ofcom is undertaking yet another valuation of how much Classic FM (plus the two national AM commercial stations) will pay during the seven years of its new licence, following the expiry of the current one in September 2011. Has Ofcom apologised for getting its sums so badly wrong in 2006? Of course not. Will it make a more realistic go of it this time around? Well, the signs are not good.

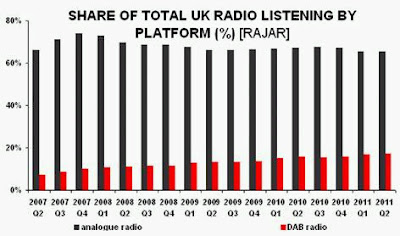

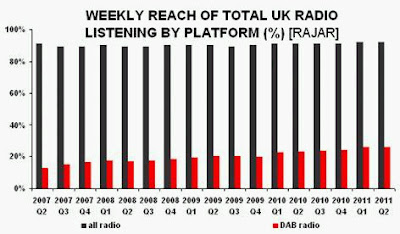

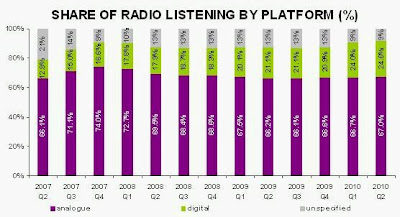

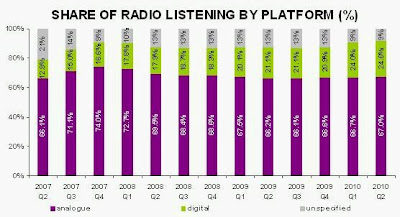

In its consultation document on this issue, Ofcom has repeated the same errors it made in other recent publications about the take-up of digital radio. In Figure 1, Ofcom claims that analogue platforms’ share of all radio listening has fallen from 87% in 2007 to 76% in 2010. This is untrue. As noted in my previous blog entry, listening to analogue radio has remained remarkably static over this time period. Ofcom’s graph has completely ignored the existence of ‘unspecified’ platform listening, the volume of which has varied significantly in different surveys. The graph below plots the actual numbers from industry RAJAR data.

Exactly the same issue impacts the accuracy of Figure 3 in the Ofcom consultation, which purports to show that analogue listening to Classic FM fell from 86% to 72% between 2007 and 2010. Once again, this must be factually wrong. Once again, the volume of ‘unspecified’ listening to Classic FM has simply been ignored and the decline of analogue listening to Classic FM has probably been overstated by Ofcom.

Confusingly, the platform data for Classic FM cited in Figure 3 differ from data in a different Ofcom document [Figure 3.34 on page 33 of The Communications Market 2010] which state that, in Q1 2010, 65% of listening to Classic FM was via analogue, 26% was via digital and 9% was unspecified. In Figure 3, the values for the same quarter are stated as 72%, 28% and 0% respectively. It is impossible for both assertions to be correct.

These inaccuracies have the impact of painting a quite different picture of Classic FM’s transition from analogue to digital listening than the market reality. These matters are not academic. They will have a direct and significant impact on the perceived value of the Classic FM licence over the duration of its next seven-year period. Sensible decisions about the value of the station’s licence cannot be made on the basis of factually inaccurate market data published by Ofcom.

Undeniably, Ofcom is between a rock and a hard place:

• An admittance that, in 2006, Ofcom got its digital radio forecast and its sums badly wrong and, as a result, has already lost the Treasury millions of pounds in radio licence fees, would require humility (and humiliation)

• Not admitting that, in 2006, Ofcom got it wrong would necessitate it to now fix the Classic FM licence fee at the same low rate as in 2006, or even lower, denying the Treasury millions more in lost revenue between 2011 and 2018

• Increasing the cost of Classic FM’s licence fee would be a tacit admittance by Ofcom that its entire DAB ‘future of radio’ policy is simply not becoming reality and that FM spectrum will still remain “extremely valuable for broadcasters”.

In 2006, the low valuation of Classic FM’s licence fee was built upon a top-down bureaucratic strategy which insisted that the UK radio industry was ‘going digital’, whether or not consumers wanted to or not. Now, it is even more evident than it was then that consumers are not taking up DAB radio at a rate that will ever lead to ‘digital switchover’ (whatever that phrase might mean).

However, reading the Ofcom consultation document, it is also evident that the regulator remains wedded to its digital radio policy, however unrealistic:

“We consider that this [Digital Radio] Action Plan is relevant when considering future trends in the amount of digital listening since it represents an ambition on behalf of the industry and Government to increase the amount of digital listening in the next few years.”

In the real world, Classic FM’s owner understands precisely what the international delegations who met in St Petersburg also knew – FM will remain the dominant broadcast platform for radio. Only the UK government and Ofcom seem not to accept this reality, still trying to go their own merry way, while the rest of Europe has already acknowledged at this meeting that:

• The FM band is “extremely valuable for broadcasters”

• The FM band is “currently, and for the foreseeable future, the broadcasting system supporting the only viable business model for radio (free-to-air) in most European countries”

• “No universal switch-off date for analogue services in Band II can be considered.”

[thanks to Eivind Engberg]