Click here for my latest presentation containing data for the UK commercial radio industry’s key performance metrics in Q4 2008 on revenues, audiences and receiver sales.

Revenues

Commercial radio had started 2008 positively with revenues in Q1 up 7.3% year-on-year. After that, everything slid downhill. Q2 revenues were down 10.1%, Q3 down 7.8% and Q4 down 14.5% year-on-year. 2008 ended with Q4 revenues of £129m, the worst performing quarter since 1999. However, in 1999, only 244 commercial radio stations had been licensed, whereas that total now exceeds 300. The result is a revenue squeeze on commercial radio businesses unseen since the 1990/1 recession.

The present situation is a direct result of a severe contraction in national advertising expenditure on radio, the last three quarters’ totals having been down 15.9%, 12.2% and 21.2% respectively year-on-year. Whereas, in 1990, national advertising had accounted for 47% of commercial radio’s total revenues, by 1999 it was contributing 67%. National advertisers’ enthusiasm for radio had contributed significantly to the commercial sector’s growth in the 1990s, but it has also made the medium more vulnerable to national economic trends and the shifting marketing priorities of the big brands.

Although more concentrated sector consolidation had once been touted as the saviour of the commercial radio industry, the sector is now in grave danger of being crucified by the very policy for which it had lobbied. Two owners now control two thirds of the UK commercial radio industry, which would render the potential failure of one of them a catastrophe of hitherto unseen magnitude. Current economic pressures are likely to create casualties at both ends of the scale, with some smaller radio groups proving just as likely to run out of cash as their larger rivals. Whether your radio group’s bank loan is £2m or £100m, debt servicing has now become your biggest headache.

Audiences

With so much industry attention focused on sharply falling revenues and the necessity to cut group central costs and station overheads, it is inevitable that investment in content has not been a current priority for many players. Total hours listened to commercial radio (427m per week) have continued their long-term decline, with Q4 2008 being marked as the second worst quarter this millennium (Q1 2008 was the worst). Although commercial radio’s audience reach has been maintained, average time listened fell back to 13.7 hours per week in Q4 2008, equal to the all-time low in Q1 2008.

The blame for these declines can be laid at the ears of listeners aged under 35, who are choosing to spend less time with commercial radio. Over the last eight years, 15-24 year olds’ listening to commercial radio has fallen from an average 15.3 to 12.8 hours per week, while 25-34 year olds’ listening has fallen from 16.1 to 13.1 hours per week over the same period. These changes, combined with the declining numbers of these younger demographics within the UK population, can only make commercial radio more susceptible to long-term decline.

At the same time, the BBC continues to chip away at commercial radio’s ‘heartland audience’ of 15-44 year olds, with Radio Two maintaining its position as the UK’s most listened to station. In London, the BBC performed particularly well in Q4 2008, pushing commercial radio’s share of listening below 50% for the first time probably since the early 1990s. As noted previously, commercial stations outnumber BBC stations in London by a factor of three, demonstrating that it is ‘quality’ rather than ‘quantity’ that creates success with listeners.

Digital Radio

The grim figures for digital radio only add to the commercial sector’s woes. Although cumulative sales of DAB receivers passed 8.5m in Q4 2008, unit sales were down 10% year-on-year, the first occasion that the vital Christmas quarter has exhibited negative growth. The danger is that the relatively high price tag of DAB radios will not entice buyers in Credit Crunch UK, particularly when the content offered on the platform is not being expanded or enhanced.

It is ‘content’ that continues to hold back digital platform growth. Only 4.6% of commercial radio listening was attributed to digital-only radio stations in Q4 2008, the lowest level since 2007, and a consequence of several commercial digital station closures in 2008. An increasing proportion of commercial radio listening via digital platforms is to stations already available on analogue (76% in Q4, up from 72% a year earlier) which demonstrates that exclusive digital content is not effectively driving consumer uptake.

Although the radio industry has been busy with discussions about the future of the DAB platform for more than a year now, almost nothing has changed from the perspective of the consumer. In Q4 2008, Bauer closed five-year old Mojo Radio, Sunrise closed five-year old Easy Radio, and Islam Radio in Bradford closed. The revived Jazz FM replaced GMG brands on four regional DAB multiplexes, but owner The Local Radio Company is already seeking a sale of this digital station.

As noted previously, many of the remaining digital-only stations (both commercial and BBC) suffered significant audience losses in Q4 2008.

Commercial Radio Station Transactions

As yet, there has been no announcement from Global Radio as to the sale of its local stations in West and East Midlands that had been required by the Office of Fair Trading in August 2008 as a condition of its acquisition of GCap Media.

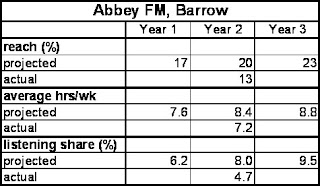

On 31 August 2008, Global Radio quietly handed back the AM licence for its Gold brand in Exeter and Torbay. On 23 December 2008, UTV closed its Talk 107 station in Edinburgh. On 30 January 2009, Abbey FM in South Cumbria was closed by joint owners CN Radio, The Local Radio Company and The Radio Business. In November 2008, CN Group had said it would close its Touch FM stations in Coventry and Banbury if it did not find a seller, but nothing further has been reported. Ofcom decided at its November 2008 radio meeting to “start formal licence revocation proceedings” against KCR FM in Knowsley which has been “failing to broadcast in line with its licensed format” since 24 October 2008.

In September 2008, UKRD sold Star Radio in Cheltenham to a local company, and The Revolution in Rochdale to Steve Penk. Tindle Radio sold Dream 107.7 in Chelmsford to Adventure Radio in September 2008, and sold Dream 107.2 in Winchester to Town & Country Broadcasting in November 2008. In January 2009, UTV sold Imagine FM in Stockport to Damian Walsh. In February 2009, UKRD sold Star Radio in Bristol to Tomahawk Radio. No prices were reported for any of these transactions.

The insolvency of Laser Broadcasting in November 2008 resulted in control of five of its licences – Bath FM, Brunel FM in Swindon, 3TR in Warminster and QuayWest in Bridgwater and Minehead – being transferred to Southwest Radio. It appears that control of Laser’s Sunshine FM in Hereford & Monmouth has transferred to Murfin Music.

The Local Radio Company, one of only two remaining plc’s in the radio sector, is seeking to raise £1.51m gross through a share issue. The company’s auditors noted on 5 March 2009 that “until it is successfully completed there remains in existence a material uncertainty which may cast significant doubt about the Company’s ability to continue as a going concern”. These concerns, which could apply equally to several other radio groups, are likely to result in a rash of transactions and an unprecedented number of station closures during the rest of this year.