Most of us mere mortals spend our lives trying to persuade people to give us what we want. We have to persuade our parents to buy us a new toy, persuade a potential employer to offer us a job, persuade the bank manager to give us a business loan. To make these things happen, we are taught to always be careful what we say – “Mind your P’s and Q’s”, our parents told us.

For the wealthy, there is little need for self-control over what comes out of their mouths. Whereas our only power derives from what is in our head, the power of the wealthy derives from what is in their offshore bank accounts. “P’s and Q’s” are barely a necessity when a platinum credit card can be flashed. Money obviates the need for persuasion. So the wealthy can pretty much say what they like, knowing that ‘money talks’ on their behalf, and it certainly seems to talk more loudly than any persuasion that the rest of us can muster.

This week we saw an outburst in The Guardian that would have done any rich, spoilt brat proud. But no, this was the founder and CEO of Global Group, Ashley Tabor, which owns Global Radio, the UK’s largest commercial radio group, demanding that the BBC “put their money where their mouth is” and invest more in DAB radio:

“Tabor said his company, which owns Heart, Classic FM, Capital and LBC, would not invest in new digital services until the DAB signal was sufficiently strong and widespread to match that currently provided by FM. He said the cost of the rollout of DAB and the strengthening of the signal in areas which can already receive it – estimated at between £150m and £200m – was the sole responsibility of the BBC. […]

‘Global has stepped up and said we are absolutely doing it, we have great new ideas of things we could do on digital but we are not going to bloody do it until our listeners can hear it in decent quality and that is something that we have been clear from the start the Beeb will need to do,’ said Tabor, the Global Group founder and chief executive. ‘They have always said yes [and] now is the time to do it. A lot of pressure is building on them to now actually put their money where their mouth is. It’s not actually a lot of money because it’s amortised over 10-12 years. I think it will happen’” [The Guardian removed ‘bloody’ from later editions].

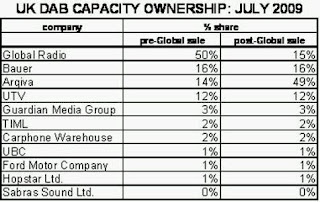

Was I the only one baffled by Ashley’s line of argument? Although commercial interests own the lion’s share of DAB in the UK, the largest commercial radio group is insisting here that the cost of fixing DAB to make it work properly is the “sole responsibility” of the publicly funded BBC. Furthermore, Global Radio will only launch new commercial digital radio stations, from which it must expect to make a profit, once the BBC has underwritten the huge cost of making the DAB system fit for purpose using public funds. I remain baffled.

This was by no means the first time, and will probably not be last, that Global Radio has talked rubbish publicly about DAB radio. In its PR, Global paints itself as a driving force behind digital radio and is constantly demanding that DAB switchover be implemented as quickly as possibly. However, in practice, Global has shown no interest in developing DAB as a replacement for FM, having sold off the majority of its DAB licences. This hypocrisy has been documented on previous occasions in this blog, during which time Global’s attitude towards the BBC has shifted from ‘carrot’ to ‘stick’. History speaks volumes.

In October 2007, Global Radio cancelled the contract with Sky inherited from its acquisition of Chrysalis Radio that would have created a national Sky News Radio station on DAB. A Global spokesperson said then that “Global was not prepared to make the necessary investment in this project.”

In December 2007, Global Radio dropped live presenters from the digital radio station The Arrow which it had also acquired from Chrysalis Radio. The Arrow was removed from DAB in London in May 2008, removed from DAB in Scotland in February 2009, removed from satellite and cable TV in June 2009, and removed from DAB in the West Country in February 2010. It is now available over-the-air on only 5 local DAB multiplexes.

In January 2008, Global Radio dropped dedicated shows from the digital version of its Galaxy Radio brand, replacing them with simulcasts of local FM output.

On 31 March 2008, the day after Global Radio’s offer to acquire GCap Media had been accepted, the latter’s two remaining national DAB radio stations Capital Life and TheJazz were closed. GCap had already closed another national DAB station, Core, in January 2008.

In March 2009, Global Radio dropped digital-only station Chill from DAB multiplexes in Leicester, Nottingham and West Wiltshire. Chill was then removed from further local DAB multiplexes in July 2009, and from cable TV in July 2010. It is now available over-the-air on DAB only in London and Birmingham.

However, in April 2009, Ashley said that he appreciated that the BBC had the capacity to make a significant contribution to facilitate Digital Britain from a radio perspective, and that Global Radio was prepared to play a leading role. Confusingly, this was the same month it was announced that Global Radio had agreed terms to sell the majority of its DAB multiplex licenses.

In May 2009, in an interview bizarrely headlined ‘Global evangelist for digital radio: Ashley Tabor has a clear vision for his group…’, he said:

“I am really confident now that all the right things are happening that will get us to where we need to go. We are in favour of [analogue radio] switch-off, so can we do it quickly please?”

That same month, Ashley’s right-hand man at Global Radio, Stephen Miron, told a radio conference:

• “The future of our sector is intrinsically linked to the successful implementation of the government’s digital strategy and to the successful migration to DAB”

• “We need more of this in the coming weeks and months. Not just words, but action”

• “We need to get our act together to make the best possible case for consumers to switch to digital”

• “Global is up for the challenge and, as the largest commercial player, we are prepared to lead this charge.”

In July 2009, Global announced the completion of the sale of its DAB licences, the largest ever transaction of its type, which drastically shifted the dominant ownership of the UK’s commercial radio DAB system from the commercial radio sector itself to transmission specialist Arqiva.

Global Radio sold:

• its 63% shareholding in Digital One, the sole national DAB multiplex for commercial radio

• its 100% shareholding in Now Digital Ltd and Now Digital (Southern) Ltd, its local DAB multiplexes

• 12% of MXR Holdings Ltd.

These transactions left Global Radio with a 51% shareholding in MXR, owner of five regional DAB multiplexes, a half-stake in 3 CE Digital local multiplexes and a minority stake in Digital Radio Group, owner of one London multiplex. At a stroke, Global’s role in DAB had been reduced from the dominant player to an also-ran. However, this did not prevent Ashley from stating in the press release announcing these disposals:

“As a company we are leading the commercial radio industry in its drive to digital.”

Neither this press release, nor the Annual Accounts, revealed how much Global Radio commanded for its sale of these assets. All we know is that the last, shortlived chief executive at GCap Media, Fru Hazlitt, was so disenamoured of DAB that she had planned to sell the company’s controlling stake in the DAB national multiplex licence for £1 in January 2008 (the transaction was halted by Global’s offer for GCap).

None of these closures and disposals seemed to change Global Radio’s public enthusiasm for DAB radio. In July 2010, a government press release on digital radio included a quote from Ashley saying:

“We look forward to working with the government and other partners to bring the benefits of digital radio to a growing group of listeners.”

So what precipitated the change of heart in Ashley’s previously collaborative noises to the BBC from a ‘carrot’ into the ‘stick’ evident in his interview this week? Well, less than 24 hours earlier, the government had published a report on DAB radio switchover that was critical of many radio sector stakeholders for the lack of progress that had been made during the last decade. Those criticised included commercial radio, its trade body RadioCentre, the Digital Radio Development Bureau and its successor, Digital Radio UK. Some people can take measured criticisms like this in their stride. But others cannot.

Not only does Global Radio account for 38% of UK commercial radio listening, but the group funds a substantial portion of RadioCentre (£2.8m in subscriptions between September 2007 and March 2009) and of the Digital Radio Development Bureau and Digital Radio UK. Even so, why did this new government report exercise Ashley so much? Because:

• Global Radio needs DAB switchover to succeed for the company to hang on to its valuable analogue radio licences

• The responsibility for making DAB switchover happen now lies elsewhere, so Ashley has decided to pin the tail on the BBC.

Maybe Ashley is a graduate of the Malcolm McLaren and Stevo school of negotiation. This is the strategy where you make the most outrageous demands and the other person caves in for fear of not being invited to your party. This might work in the unregulated music business, where excess is viewed as a virtue, but in the radio industry there are laws and rules governing large parts of the business.

What would be the response of record companies if a radio owner were to march in and tell them that they should pay radio stations for playing their music, rather than the other way around? Or if you were to tell record companies that your radio stations would no longer play ‘hit’ records that line their coffers but, instead, would deliberately play unpopular songs that they did not want on the radio. Record company bosses would probably laugh in your face and ask their legal department to show you a filing cabinet full of royalty agreements with commercial radio dating back to 1973.

Getting your own way, all the time, only works when you have been given absolute power over your fag. Ashley phoning a journalist, stomping his feet at the BBC and demanding that it do this or that will have no effect whatsoever. His demands about DAB must have had BBC radio managers laughing their socks off on Wednesday morning. As Scott Taunton, the straight-talking managing director of UTV Radio, said of Ashley in 2009:

“He is a guy who is used to getting his own way. He isn’t from the same school of business, the same school of negotiation, that I am.”

So why exactly does Global Radio need DAB switchover to happen? Because:

• Global Radio was created by Ashley’s millionaire father for a son who is a radio obsessive (“I would literally have a radio in my [school] bag and the second I was allowed to put it on I would actually phone [presenter] Pat Sharp in the studio at whatever time, 10.30, 11.30, just to say hello and develop a relationship with him. He thought I was nuts,” said Ashley)

• Global Radio overpaid to acquire GCap Media in June 2008 for £375m, a mis-managed company whose performance was dropping like a stone, and whose market capitalisation had fallen from £711m in 2005 to £200m by year-end 2007

• Global Radio has already had to write down its assets by £194m in March 2009, reducing the group’s net book value to £351m from the total £545m it had paid for Chrysalis and GCap in 2007 and 2008 respectively

• Global Radio “is primarily funded by debt”, its accounts state, and external bank debt was £110m in October 2009, an amount that must be repaid in quarterly instalments by October 2012

• Global Radio has been hit hard in 2010 by the new government’s sudden 50% cut to its advertising spend (“The COI change has been larger than expected, very abrupt. It’s been pretty severe, more than 50%,” said Ashley)

• Ofcom is presently re-evaluating the price of Global Radio’s Classic FM licence, the most profitable in commercial radio and, if DAB switchover is abolished, the cost of that licence could be increased from its current £50,000 per annum to nearer £1m per annum from 2011 to 2018

• The Digital Economy Act 2010 renewed commercial radio licences for a further seven years only on the basis that DAB switchover will happen. If switchover does not happen, the government has the power to terminate all renewed licences by 2015 (or by two years’ notice, if later). However, in its accounts, Global decided to write off the ‘goodwill’ of its GCap acquisitions over twenty years.

For Global Radio, which owns more analogue licences than any other commercial radio group, this means that the value of its business could be reduced drastically if DAB switchover does not happen. Its one national licence would become a lot more expensive and then might have to be publicly auctioned, while its dozens of local licences could be terminated earlier than anticipated. Global needs DAB switchover to happen at all costs.

However, at every opportunity, Global decided to forgo investment in the DAB platform and, instead, to dispose of the majority of its DAB assets. This has left it with almost no remaining leverage to ensure that DAB switchover will ever happen. Furthermore, Ashley has alienated commercial radio competitors such as UTV, precipitating its resignation from the trade body RadioCentre in 2009. UTV’s Scott Taunton described Ashley as a “rich man’s son” and explained:

“For us it came down to Global, as the largest funder of the RadioCentre, making sure that the policies of the RadioCentre were in the interests of Global Radio. At times, for me, that meant the [trade body] was pursuing an agenda that wasn’t necessarily in the interests of all its members.”

So, Global Radio needs DAB switchover to happen in order to maintain the value of its analogue radio business. But it can do little itself directly, its biggest competitor Bauer is unlikely to help, and its smaller competitors have been alienated. Global had succeeded in wrangling a very beneficial deal from Lord Carter in the Digital Economy Act, but Carter exited quickly and the whole government has changed since then. The sting in the tail was that parliament included a get-out clause (if DAB switchover does not happen …) and now that clause looks more likely than ever to be invoked.

The pheasants look as if they might be coming home to roost at the Tabor estate. And what does a young man do when the train set his father made for him is not working the way he wants? He stomps his feet. He shouts. He issues demands. This week, the BBC has been on the receiving end. It should feel honoured. Ashley has demonstrated his belief that the BBC can do more to fix the DAB disaster than the whole of the commercial radio sector and its trade and marketing agencies added together. But, remind me, why should part of my BBC Licence Fee go to fix his plaything?

And what might Ashley think of doing next if the BBC does not bow to exactly what he wants? Will he be demanding that BBC director general Mark Thompson stands on his head in the corridor during short break, or runs around the perimeter of White City in his underwear fifty times in the pouring rain, or sits in the BBC library after work copying out chapters of ‘Paradise Lost’ by hand?

Are any of these shenanigans a strategy for the future of radio? All they demonstrate to the world is that large parts of the UK commercial radio sector seem to have completely lost the plot.

[declaration of interest: I was paid to advise DMGT on the offer made for GCap Media by Global Radio in 2008]