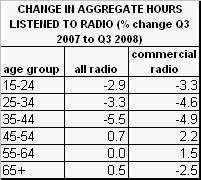

[source: RAJAR]

So who is working the hardest to enable and promote the notion of radio listening amongst young people? Could it be Nokia?

Nokia had a 38% market share last quarter of mobile devices globally. In Q3 2008, Nokia sold a staggering 118m mobile devices worldwide, 27.4m of which were in Europe. In the UK, of the 94 Nokia models available, 70 include FM radios and 24 include Wi-Fi capability (19 have both FM radio and Wi-Fi). As a result, the overwhelming majority of new Nokia devices sold in the UK offer consumers listening to either FM broadcast radio and/or IP-delivered radio connected via Wi-Fi. Does this make Nokia the biggest selling brand of radio receivers in the world?

Would not a generic campaign to promote radio listening on mobile phones prove a worthwhile marketing project to be funded jointly by commercial radio and the BBC? The mobile phone hardware is (literally) already sitting in millions of people’s pockets, offering them the capability to listen to radio. Of course, mobile phone operators are never going to promote the radio listening function on the handsets they sell, for the simple reason that it earns them no revenues, and every quarter-hour spent listening to the radio is a quarter-hour lost of phone usage.

Is the UK radio industry capitalising on this huge volume of FM receivers incorporated into phones with which Nokia and its competitors are flooding the market, but whose radio function seems to sit mostly unused in people’s pockets and handbags? Seemingly, no. Instead, the industry is wedded to the notion of spending millions of marketing pounds trying to convince consumers to purchase yet another piece of hardware that enables them to receive the ‘DAB’ digital radio platform. The hurdle is that the average retail price of a DAB radio receiver is still £90+.

In this converged world, is there a mobile phone available in the UK that incorporates the DAB platform? No. Why not? Because ‘FM radio’ is a long established, global broadcast platform used in almost every country, whereas the ‘DAB radio’ system is only commercially underway in the UK, Denmark, Norway and, imminently, Australia and China. Will ‘DAB radio’ ever become a global system that replaces ‘FM radio’? No, because the US (the biggest consumer electronics market in the world) has already adopted a completely different digital radio standard. Would Nokia make a phone that includes DAB? Despite a recent report, it would seem highly unlikely. The consumer market for DAB simply isn’t big enough for a global player like Nokia.

Which is precisely why UK receiver manufacturers, such as Pure and Roberts, continue to dominate our domestic market for DAB radio hardware – the addressable market is simply not big enough for most global brands to be interested in ‘DAB radio’. But neither Pure nor Roberts will ever make mobile phones or cool-design i-Pods that include DAB radio and which might appeal to fashion-conscious, brand-obsessed, young people. As a result, the DAB platform is condemned to be largely the province of older demographics who listen at home on DAB ‘kitchen radios’. And, importantly, they are mostly listening to their same, favourite analogue stations via DAB platform simulcasts that they used to listen to on FM/AM. New, digital-only radio stations barely get a look-in in the radio ratings.

Neither do the UK sales figures of DAB hardware look particularly impressive, compared to Nokia’s success in pumping FM radios into the market. In the decade since DAB was introduced, more than 7m DAB receivers have been sold. But, during the last year alone, more than 8m analogue radios were sold in the UK. Amazingly, 79% of new radios sold in the UK during the last year were analogue, rather than DAB. Despite a landmark pronouncement in 2006 by online electronics retailer Dixons that it would no longer sell analogue radios, consumers have continued to demonstrate their interest in purchasing inexpensive AM/FM radios. Dixons has been forced to eat humble pie and now stocks four models of analogue portable radio, the cheapest of which is £8.79, alongside 38 models of DAB radio, the cheapest of which is three times that price.

In the face of consumer reticence, the UK commercial radio industry, supported by Ofcom and the government, has been busy the last decade desperately trying to persuade the public to migrate its radio listening to the DAB platform. The sticking point here is the pre-requisite for consumers to spend considerable sums replacing all the analogue radios they own with more expensive, new digital ones. Meanwhile, global heavyweights like Nokia, pursuing their own strategy to satisfy consumer needs, continue to supply the market with millions of analogue FM radios incorporated into a myriad of converged, portable devices. Could the UK government ‘persuade’ Nokia not to push its FM radios in the UK market? Er, probably not. In which case, its proposed analogue radio ‘switch-off’ remains a completely lost cause.

Perhaps instead of viewing Nokia and its ilk as an irrelevancy to its long-held digital migration plans, the UK radio industry needs to simply capitalise on the massive penetration of FM-enabled (and now IP-enabled) phones already within the consumer electronics market. These phones are the ‘sleeping giant’ that could potentially reinvigorate radio listening, particularly amongst the young demographics. All their owners need is a ‘call to action’ – a marketing campaign to make them realise that they already have the world’s most immediate, live, portable broadcast medium in their pocket.

[many thanks to Daniel for the idea for this post]