The Digital Radio Development Bureau [DRDB] announced yesterday that, after a one-year trial, Ofcom “has agreed to put in place a permanent licensing regime for all retailers across the country” to install DAB repeaters that will boost the signal in-store. According to DRDB:

“Many electrical retailers suffer from poor analogue and DAB signal strength due to the steel framed infrastructure of the building or their basement location. Installing a DAB repeater on the roof of the store means a signal can be boosted in-store and DAB radios can more easily be demonstrated, thus increasing sales potential.”

Currys owner DSGi’s Trading Manager Amanda Cottrell said:

“We know from experience that demonstrating DAB radio in-store is the best way to show consumers the benefits of more station choice, ease of tuning and clean, digital quality sound. Consumers like to get hands-on with new technology and these DAB repeaters will help us to maximise sales in areas where demonstration was a problem.”

I understand the retail sales floor problem, but am I the only one worried that the solution implemented here might not be quite appropriate? I admit it is a very long time since I studied consumer law (1981, Durham Technical College), but my thinking is that these actions could potentially lead to consumer redress under UK legislation. Have the legal eagles at Ofcom considered this fully?

Under Section 15 of the Sale Of Goods Act 1979, when goods are sold by ‘sample’ (ie: consumer sees in-store demonstration sample of DAB radio receiver, but store supplies consumer with sealed, boxed good), “the goods must correspond to the sample in quality”. The law requires “that the goods will be free from any defect, making their quality unsatisfactory, which would not be apparent on reasonable examination of the sample” [my emphasis].

Under the new ‘repeater’ system, when the consumer examines the in-store sample of the DAB receiver, the receiver will be capable of offering ‘perfect’ reception of DAB radio stations. This is due to the installation of special in-store equipment. A fixed antenna has been installed on the roof of the building, pointed directly to the nearest DAB transmitter mast, and its received signal supplies a relay transmitter (transmitting the same stations) placed on the shop floor adjacent to the DAB radio receiver demonstration area.

When the consumer takes the sealed, boxed DAB radio home, they may open it and find that reception of radio stations on their hardware is not as good as it was in-store. This is because their radio is not receiving the DAB signal from a relay transmitter only metres away from the receiver, as it was in-store. Instead, it is receiving signals from the nearest DAB transmitter, probably miles away, and that signal may or may not penetrate the building in which they are using the radio.

The consumer could theoretically apply to Ofcom to install a relay transmitter in their home, in order to replicate the precise conditions in which the sample DAB receiver was demonstrated in-store. Ofcom’s response to the consumer’s application would certainly be ‘no’. Thus, the in-store ‘sample’ DAB receiver was purposefully demonstrated to the consumer under an artificially created environment that cannot ever be reproduced within the consumer’s home.

This would not be the first time that the marketing of DAB radio in the UK has come under legal scrutiny for potentially misleading consumers. In 2004, Ofcom banned an advertisement broadcast on London station Jazz FM which had claimed falsely that DAB radio offers consumers “CD-quality sound”. In 2005, the Advertising Standards Authority upheld a complaint against DAB multiplex owner Switchdigital for a misleading radio advert which had claimed that DAB radio was “distortion free” and “crystal clear”. In its verdict, the ASA said it had “received no evidence to show that DAB digital radio was superior to analogue radio in terms of audio quality”.

The problems concerning the paucity of DAB reception in some circumstances (basements, steel buildings, built-up areas) have been known to the broadcast industry for a long time. At the 2006 TechCon event, Grae Allen, then manager of digital distribution at EMAP Radio, had explained that “[the] Wiesbaden 1995 [radio conference] and all the other DAB planning dealt with mobile reception – in-car and portable outdoors. It made assumptions about aerial heights being just above ground level and, to provide good service to 99% of locations, the conclusion was that it required 58dbųV per metre to maintain that quality of service, and it made some assumptions about the performance of receivers and aerials.” In practice, he said, “some receivers do not quite live up to expectations – some have lossy aerial systems and suffer from self-noise.” Grae said that 2006’s European Regional Radio Conference “[was] moving DAB to become a truly indoor medium. The new planning model has around 10dbųV higher field strength than was envisaged in the original plan.”

In 2006, BT Movio had been about to launch a mobile TV service using DAB spectrum, and Grae said: “That raises a question. We are seeing increasing numbers of hand-held receivers, such as the BT Movio receiver, that do not have an aerial of any significant size. So, in some areas, we may have to go to higher field strengths to deliver to handhelds indoors. So how are we going to improve the coverage? Unfortunately, the people who fill in RAJAR diaries don’t tend to live in large numbers alongside the sheep in the fields [where DAB transmitters are mostly located]. They live in the cities and the urban sprawl, and that’s where we need to deliver the high field strengths that are required for the types of receivers that are becoming popular, and the level of service that is expected. In the future, as I envisage it, we will see a need to put more and more [transmitter] sites inside the cities in areas where we actually need significant power where people are living and working.”

Mark Thomas, then head of broadcast technical policy at Ofcom, admitted at the 2006 TechCon event that the original DAB power allocations had proven too low: “The Radio Authority had no data of how [DAB] receivers performed, so it had to make some very broad-brush assumptions. More recently, now that we have a lot of receivers in the market and we can see how they behave, an industry group has been working under Ofcom’s chairmanship for the last two years to look into the issue in more detail and come up with some modus operandi for new transmitter sites”. Mark concluded: “The Ofcom approach is that the industry co-operates between commercial operators with each other, and with the BBC, in identifying the sites that will improve field strength of DAB services to consumers and will also avoid the issues surrounding Adjacent Channel Interference. ACI also adds to the investment challenge that all of this spectrum development is building.”

Now zoom forward from 2006 to December 2008 and read the Final Report of the Digital Radio Working Group, which said:

“We believe that action is needed to improve the quality and robustness of the existing [DAB] multiplexes’ coverage. We recognise that such a request has significant financial implications for multiplex operators…”

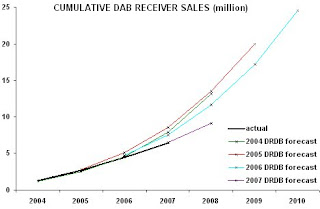

So, it would appear that, from 2004 onwards (when Mark acknowledges Ofcom was aware of the problem), the UK radio industry has continued to market and sell millions of DAB radios to UK consumers, in the full knowledge that its DAB transmission infrastructure requires a significant upgrade to provide consumers with sufficiently robust DAB radio reception in built-up areas and in homes.

The latest DRDB ‘repeater’ sales initiative merely tackles the symptom of poor DAB reception which has existed for years, and the solution is limited entirely to electronics retailers. What is still missing is a solution to the core problem of the “quality and robustness” of DAB radio reception….. for consumers.

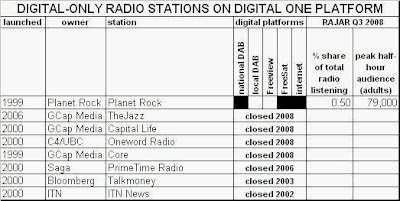

It hardly inspires confidence in the Digital One DAB platform that Global Radio’s predecessor, GCap Media, closed three of its own digital-only stations carried on its platform last year, and sold Planet Rock to an entrepreneur with no other radio interests. Neither is it a good advertisement for Digital One that its

It hardly inspires confidence in the Digital One DAB platform that Global Radio’s predecessor, GCap Media, closed three of its own digital-only stations carried on its platform last year, and sold Planet Rock to an entrepreneur with no other radio interests. Neither is it a good advertisement for Digital One that its