Tag: FM radio

FRANCE: government report recommends 2-3 year "moratorium" before launch of digital radio

A new report on the introduction of digital terrestrial radio (‘DAB radio’ in the UK) in France has recommended to the government that the launch should be delayed by two to three years. In the interim, the French media regulator CSA would be asked to establish a project to investigate the “overseas experiences” of digital radio, according to the government press release.

David Kessler, former head of state radio station France Culture, was commissioned in June 2010 by the government to produce a strategic analysis of the launch of digital radio in France. His interim report, published in November 2010 [see blog], identified the “paradox of DAB radio – it is a sufficiently attractive technology to be launched successfully, but it is insufficiently attractive to successfully allow FM broadcasts to cease.”

In the final report, published this week, Kessler said that not all the conditions had been met from an economic standpoint to permit the widespread launch of digital terrestrial radio. His report identified the significantly different challenges between digital radio switchover and digital television switchover:

“An error in logic has probably contributed greatly to making the debate [about digital radio] opaque rather than transparent. The error came from having planned digital radio switchover with reference to digital television switchover, which started in 2005 and the success of which has been staggering and immediate, so that the changeover from analogue to digital TV will be completed throughout the land by 2012. Many parties imagined that the route to digital opened up by television would be followed by radio. But this plan was wrong for three reasons.

Firstly, the television market was dominated in 2005 by five channels (TF1, France 2, France 3, France 5/Arte and M6) that attracted 75% of television viewing. The transition to a score of free channels was obviously very attractive. However, as will be discussed later, the situation in radio is quite different – the current choice of stations is one of the richest that exists in the world, after the landscape opened up in the 80s. Even if the choice is not the same in every region, none of them – some near – are in a situation where only five major stations dominate the choice.

Second is the difference in receivers. Even if digital radio switchover had been launched simultaneously with that of television, where the evolution of televisions (flat screen, HD and now 3D) resulted in a faster replacement of equipment than anticipated, digital television was accessible without changing the set through the purchase of a single adaptor at a moderate price. Digital radio switchover requires the replacement of all receivers, and households have multiple radios and the market is sluggish. Without doubt, digital radio switchover could re-invigorate the market with a simple, inexpensive high-end (with screen) radio. At this point, no one can say how quickly take-up of replacement receivers will happen. Examples overseas – particularly Britain – demonstrate a relatively slow rate of replacement, and the different situation in countries where take-up is faster – Korea, Australia – make comparisons difficult.

The third reason is that the history of television demonstrates that it works through ‘exclusive changes’ where one technology replaces another quickly. Colour television pushed out black and white television. Digital television is about to push out analogue television. But experience shows that far from all media work this way. On the contrary, some go through ‘cumulative change’. Over a short or long period of time, different technologies co-exist and content is distributed through several technologies. As Robert Darnton noted about the book, we often forget that the printed word has long co-existed with the manuscript. From this perspective, the history of radio is the opposite of television: different transmission systems are cumulative rather than exclusive. This does not exclude the possibility that, in the long run, some transmission systems will decline and no longer be used, just as printing marginalised the manuscript. But what it means is that one cannot plan the launch of digital radio by imagining that all other transmission systems will be switched off, particularly FM. Even today, despite the success of FM, Long Wave and Medium Wave transmissions are still used because they reach a sufficient number of listeners not be switched off by broadcasters.

In fact, a careful examination of the launch of digital radio in other European countries shows that a ‘cumulative change’ scenario exists that we must anticipate in France too. Indeed, the launch of digital radio in other European countries had been presented as a quick substitute for analogue radio, even though the existing choice of analogue stations was less than in France, and the choice of digital stations seemed more attractive and content-rich than offered by analogue. Even if a proportion of listeners are quickly adopting digital radio, a greater proportion are still sticking with their traditional radios, with the possible exception of Norway, where analogue switch-off seems to be seriously considered at present. This leads to a situation in which the government initially adopts a goal of analogue switch-off but then, given the impossibility of switch-off, drops or postpones the switch-off date by several years. As the choice of existing radio stations is particularly substantial in France, it would appear that this situation is most likely to be repeated if digital radio were to be launched. Radio station owners are not mistaken. Very few want a quick switch-off of FM, and some do not want any switch-off.”

These points echo evidence on digital radio switchover in the UK that I had presented to the House of Lords Select Committee on Communications in January 2010:

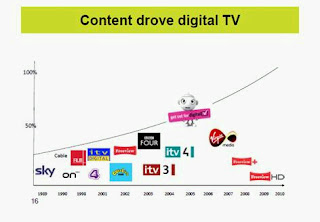

“With television, there existed consumer dissatisfaction with the limited choice of content available from the four or five available analogue terrestrial channels. This was evidenced by consumer willingness to pay subscriptions for exclusive content delivered by satellite. Consumer choice has been extended greatly by the Freeview digital terrestrial channels, many of which are available free, and the required hardware is low-cost.

Ofcom research demonstrates that there is little dissatisfaction with the choice of radio content available from analogue terrestrial channels, and there is no evidence of consumer willingness to pay for exclusive radio content. Consequently, the radio industry has proven unable to offer content on DAB of sufficient appeal to persuade consumers to purchase relatively high-cost DAB hardware in anywhere near as substantial numbers as they have purchased Freeview digital television boxes.”

The Kessler document should offer significant food for thought to the British government for its unworkable plans for DAB radio switchover. Whereas Kessler correctly identified that TV and radio digital switchover are two very different undertakings, our public servants working on digital radio policy in the government and in Ofcom have long failed to understand these differences. The appointment of Ford Ennals as chief executive of Digital Radio UK in 2009, on the back of his work between 2005 and 2008 managing digital television switchover, should have been viewed as barely relevant experience to achieve successful digital radio switchover.

Have any of the people managing digital radio switchover for the UK ever actually worked in the radio industry? At DCMS? No. At Ofcom? No. At Digital Radio UK? No. If, like Kessler, they had radio sector experience, they would realise that all their speeches and presentations that repeatedly cite digital TV switchover as the precedent for radio are completely off-target.

Is there any wonder that failure of DAB public policy was inevitable?

Which? says: DAB radio switchover must be "consumer led or not at all"

What would have to be done to make DAB radio successful?

“What there does need to be, as Freeview and digital satellite has shown in television, is simply a sufficient combination of services, technology, simplicity and price or discount to provide a value proposition for the consumer,” suggested Stephen Carter in 2004, when he was chief executive of Ofcom.

“….. for the consumer” were the key words. They were also the words that became forgotten. The consumer was ignored in the radio industry’s pursuit of the radio industry’s own agenda for DAB radio. As a consequence, DAB radio has still not succeeded … with consumers. The failings were acknowledged by Quentin Howard, one of the architects of DAB radio in the UK:

“The mistake by broadcasters was in not understanding that ‘build it and they will come’ is no longer practical in this integrated technological age.”

Which?, the UK consumer advocacy, noted the radio industry’s lack of attention to the consumer in a February 2011 briefing paper entitled ‘Digital Radio Switchover in 2015? Consumer Led Or Not At All’:

“The transition to digital radio is currently industry led. The benefits of a transition to digital radio over the current analogue service are not clear to consumers, and the uptake of the technology over the past 10 years reflects this.”

Which? suggested that, before the government can announce a date for digital radio switchover, the following criteria should be met:

• “Uptake should be a minimum of 70% of all FM radio listening transferred to digital, leaving 30% still listening on analogue (FM/LW/MW/SW) (the Government’s Digital Radio Action Plan suggests 50%)

• The transition to digital must not be announced until coverage, including a measure of signal quality, is better than that of FM radio

• DAB must have been fitted as standard in all new cars for at least two years and an effective and affordable solution to in-car conversion must be available prior to the announcement of a switchover (which costs no more than for in-home conversion)

• Government must conduct a full cost-benefit analysis from a consumer perspective as a priority because increasing consumer desire for DAB should not focus on cost alone

• Minimum standards associated with a kite mark must be ambitious and future-proofed and any incentive scheme to switch to DAB should offer only kite marked receivers

• Consumer group representatives must be involved in the development of an information campaign independent from industry to raise awareness of the digital switchover by consumers and ensure guidance and training tools are available to retailers. In this regard, any lessons from the Digital TV switchover should be acted upon

• In its assessment of the environmental impact of a switchover to digital radio, the Government must tackle the full range of issues around recycling of analogue sets and the energy impacts of DAB”

However, in some of these areas of concern, current policy on DAB radio appears to be moving in the opposite direction to that advocated by Which?:

• The 50% criterion (50% of radio listening via digital platforms before switchover can be announced) is not mandatory because it was never included in the Digital Economy Act [see Jan 2010 blog]

• The latest plan for DAB is not to deliver reception even as good as FM, but to make it worse than FM [see recent blog]

• Only 1% of cars have DAB radios fitted and future take-up will inevitably be slow [see recent blog]

• Roberts Radio reported a 35-40% customer return rate for its in-car DAB radio adaptors [see Nov 2010 blog]

• The cost benefit analysis of DAB radio to be considered by the government will also be authored by the government, rather than commissioned independently [see Jan 2011 blog]

• Roberts Radio admitted having had to pull the plug on several DAB receiver projects, including the industry’s promised ‘£25 DAB radio’, because they could not meet Roberts’ minimum quality standards

In July 2010, after the formation of the new coalition government, culture minister Ed Vaizey had said:

“If, and it is a big if, the consumer is ready, we will support a 2015 switchover date. But, as I have already said, it is the consumer, through their listening habits and purchasing decisions, who will ultimately determine the case for switchover.” [see Sep 2010 blog]

So, it might appear that the Minister and Which? are, in fact, both lined up in agreement that digital radio switchover can only happen if it is supported by consumers. So why has the government not yet recognised that consumers already seem to have given the thumbs down to DAB?

Because there are middle men (Ofcom, DCMS, Digital Radio UK, Arqiva, DAB multiplex licence owners) who persist in keeping the DAB dream alive in Whitehall. Yet again, consumers are being drowned out by the clamour of agencies eager to pursue their own narrow objectives. And the mantra of the middle men is: DAB crisis, what crisis?

David Blunkett's opinion of DAB radio: BBC is "defending the indefensible"

‘You & Yours’

BBC Radio 4

28 March 2011 @ 1200 [FM only]

Julian Worricker, presenter [JW]

Paul Everitt, chief executive, Society of Motoring Manufacturers & Traders [PE]

Laurence Harrison, technology & market director, Digital Radio UK [LH]

JW: Now, car manufacturers have long prided themselves on arming their vehicles with the latest groundbreaking technology, but there’s one in-car gadget which has remained stuck in the twentieth century. Radios in cars, generally speaking, are FM/AM analogue, and not digital. Around 20% of all radio listening takes place in the car, that’s according to RAJAR, the organisation which counts these things. So, if the UK is to go all-digital and the analogue signal switch is turned off – and that, of course, is the plan – cars need to be equipped with digital radios.

JW: Well, car manufacturers are planning that all new vehicles will have digital radios fitted from 2013. And, now, Ford says it will make digital radios available in its cars a year earlier than that. This will all help achieve the target that 50% of all radio listening should be digital, which is one of the pre-conditions for turning off the analogue signal. We can explore this with Paul Everitt, who is the chief executive of the Society of Motoring Manufacturers & Traders, and with Laurence Harrison, the technology & market director from Digital Radio UK, which is the company set up by broadcasters to help with the switchover. Gentlemen, good afternoon. Paul Everitt, why is the car industry pushing ahead with installing digital radios by 2013?

PE: Well, I think there are two key reasons. The first is because that’s the agreement we had with government as part of the Digital [Radio] Action Plan. They recognised that listening in-car was a key part of radio listenership and, therefore, early introduction of vehicles with digital radio was a key part of the package that needed to be achieved. But, I think, increasingly, what we are seeing, and certainly the announcement from Ford that you mentioned slightly earlier, is actually about the consumer saying that this is something that we want. The consumer now has an increasing opportunity to experience both the listening quality of digital in-car, but also the content, the increasing content, and desirability of the content on digital, as well as gradually and increasingly improving coverage. So, it’s a combination here of ….

JW: [interrupts]: Right, right, I just want to ….

PE: …. both something that we have to do, or we have agreed to do. But I think, increasingly, this is a push that is now coming from consumers.

JW: Okay, I just want to scrutinise that a little, because I don’t doubt that Laurence Harrison will say the same thing because we are told this is consumer led. But, surely, the truth of the matter is that the consumer has been led because of what the government requires you and others to do, so consumer choice only goes so far here.

PE: Well, I think we can argue the finer points of this, if you like. But, from an industry point of view, we began to be involved in this discussion during the course of 2008, obviously the conditions during 2009 with the development of the Digital Britain report brought that forward, or conclusions from that report have been built into vehicle manufacturers’ plans. But, as I say, what we are actually seeing today is, you know, increasing interest in digital from consumers.

JW: Okay. Let me bring Laurence Harrison in on coverage because, as I understand it, at least 90% [population] coverage is a target. That’s part of the targets that will only allow the switchover to take place. Now, 90% sounds positive until you then think about the 10% who can no longer hear what they are listening to now.

LH: Well, I think the key thing on coverage is to become the equivalent of FM coverage. So the 90% figure you refer to is around local coverage. Actually, on the coverage of national services, we are already at just over 90%, and the BBC has just recently committed to build that out to 93% by the end of this year. And the target thereafter is to get to FM equivalence as soon as we can, so that programme is well underway.

LH: And, if we are driving from A to B a significant distance, can we be sure that that coverage will remain consistent over that distance?

PE: So, you’re absolutely right. Of course, for the car market, geographical coverage is vitally important. What we do know now is that the vast majority of motorways and A roads have got good coverage, and significant coverage on B roads and smaller roads. But we are working with broadcasters to try and prioritise the road network going forward.

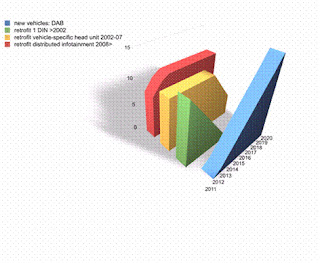

JW: Paul Everett, what about those who can’t afford to buy a new car after 2013 with a smart digital radio inside it? When that switchover eventually happens, what happens to them?

PE: Well, this has always been our biggest – or one of our biggest – concerns, which is that how do we retro-fit the entire vehicle parc? We are currently looking at something between 25 and 30 million vehicles all up, so it’s quite a challenge. What we have seen over the course of the last year – 18 months – is relatively low-cost adaptors. I think now … I mean the prices vary, but certainly less than £100 to adapt your vehicle, and these are sort of a relatively basic unit, so not desirable for everybody …

JW: What does ‘relatively basic’ mean in terms of what it will actually do?

PE: Well, it means you get a digital reception but you have to kind of plug it into the cigarette lighter and have a bit of an aerial up and …

JW: It’s a bit Heath Robinson, isn’t it?

PE: We would agree with that. From our perspective, we’ve been very much focusing on what we would see as an integrated unit. So, something that you can put into your car or have installed in your car which would effectively mean that you could just use your standard radio to receive digital broadcasts. Now, we’ve seen … I’ve seen first kind of trials of that technology. We hope that that’s going to be available from sort of around the end of this year – the beginning of next year – so we’re already seeing a market begin to develop and, as I say, I think we … well, there are two ways of looking at the problem. One is that we must all prepare because this switchover is going to happen. Or the one which we are focused on is: the more consumers have experience of digital, the more they like it and want it and therefore that’s a market driver, rather than sort of an administrative pull.

JW: No, and that’s a fair point because I read some surveys, Laurence Harrison, that I know you were quoted in in recent weeks. But the point that has just emerged from the last comment, surely, to put to you are that whatever we do here, it is going to cost us and we do not have any choice over that.

LH: Well, I think the stage we are at at the moment, as Paul said, is that we have not got a confirmed switchover date now, so what we are trying to do is build momentum.

JW: But it will happen one day.

LH: It will happen one day, but what’s going to drive people towards digital radio is the great content we’ve got. The same happened on TV. So if you look at the offering now on digital radio, you’ve got the soon to be launched BBC Radio 4 Extra on Saturday, 5 Live Sports Extra, 6 Music, Absolute 80s [and] 90s, Planet Rock, Jazz FM has just announced it is going onto the digital network, so the content offering has frankly never been better and what we do know about people that have digital radio is that once they’ve tried it, they love it.

[The programme was followed with a Yours & Yours blog which invited comments from listeners on their experiences with DAB radio in cars. David Blunkett MP submitted a comment to the programme about his experiences with DAB, upon which listeners made further comments.]

……………………………

‘You & Yours’

BBC Radio 4

1 April 2011 @ 1200 [FM only]

Peter White, presenter [PW]

David Blunkett MP [DB]

Lindsey Mack, senior project manager of digital radio, BBC [LM]

PW: Now, you’ve all been writing in, telling us about your frustrations with digital radios, after Monday’s report on how Ford is planning to install DAB radios as standard in some new cars from next year. Steve told us about his A370 journey between Cardiff and North Wales: perfect listening for 30 miles outside the Welsh capital, then nothing for 150 miles. By contrast, over on Anglesey, Steve tells us the only place that silences his DAB car radio is the Conwy Tunnel. Another correspondent was former Home Secretary, David Blunkett. He’s had trouble getting a DAB signal at his home in Derbyshire. So we brought him together with a senior digital manager for the BBC, Lindsey Mack, and David started by challenging the main claim of digital supporters that DAB achieves 90% coverage.

DB: My thrust was that there are not 90% of the population with access to digital [radio], and many of those who claim to have access have intermittent or interference with the access. And I’m a classic [case] because I can just about get digital radio in North Derbyshire, where I rent a cottage, if I hold the radio up to the roof, or I find one particular spot on the kitchen window sill. Get it out of kilter and either the signal goes or, as quite often I get, even in London, it breaks up.

PW: Right, let me at this point bring in Lindsey Mack. A lot of our e-mails mirrored what David had to say, and particularly this point: that the quality isn’t adequate for many people, even if they’re … it’s said they have reception, and in that so to talk of [FM radio] switch-off at this stage, you know, seems wrong.

LM: Over the last sort of two years, the BBC has been very committed to building out its DAB coverage. We actually are at 90% of the UK population, but that doesn’t mean that everyone’s going to always get a very good reception. A lot of it does depend on the device you have, as well. There are some receivers that are a little bit more sensitive than others. And, in fact, we’ve actually just been doing some tests on the last sort of bestselling sort of ten or dozen receivers in the market.

PW: But what a lot of people said to us, and I suspect David will reiterate this, is that FM, which digital is going to replace, that has a much more stable signal and that, even if you start to lose that signal, you don’t lose it altogether in the way you often lose the digital [signal] or it just goes into sort of burble.

LM: Yes, and with DAB, you usually either get it or you don’t. I mean, looking in Derbyshire, we’ve actually got very good coverage, especially North Derbyshire, so perhaps after this we could actually talk to David about the device he’s actually got, as well, just to see which one he’s actually using. Whilst the BBC has been very committed to DAB and extending the coverage, we are now actually having to make the existing coverage more robust, and that’s actually what we haven’t been doing as much before. What we’ve done before, we’ve concentrated on just rolling out DAB. Now we know we’ve got to really look at the whole way we’re measuring DAB. We’re looking at indoor coverage in particular. You know, originally, when we launched DAB, we actually based all our coverage on car listening and then, obviously, car listening didn’t take off the same way as people are actually listening indoors.

PW: Well, it couldn’t because there weren’t [DAB] radios in cars.

DB [laughs]: Absolutely.

LM [laughs]

DB: It is a problem, Peter, actually, that if you can’t get it and you can’t hear it, you can’t appreciate it. I’ve got no problem with the extra reach and the way in which [BBC] Radio 7 is now going to become Radio 4 Plus or, whatever, Extra. My problem is that there’s a big over-claim for this. Let’s take it steadily, let’s try and get it right, let’s not claim that people have got a service when they haven’t and, particularly, let’s not say – which was what the sell for DAB was – that this is going to be higher quality when, as you’ve just described, the burble, the break-up, the lack of a good sound… I have three DAB radios up north. I’ve tried them all in different places, so it’s: please don’t do to me and to the audience what always happens, which is: it is not the fault of the deliverer, it’s the piece of equipment you’ve got, and they’re pretty good pieces of equipment.

PW: But, David, it was your own government who published Digital Britain and it was your own government that set the 2015 date.

DB: Yeah, and I criticised them at the time. Everybody wants everything now. They want it faster, they want to claim it as the greatest quality. I mean, everything is always ‘the best ever.’ And, frankly, it isn’t and if we just accept that and say ‘lets take it steady and lets try and get it right,’ we’ll all be on the same page.

PW: So it isn’t the principle that you’re against. It’s the practice, really.

DB: Yes, it is. I mean, if FM is better than DAB, let us continue for the time being with FM and, in many parts of this country, it is.

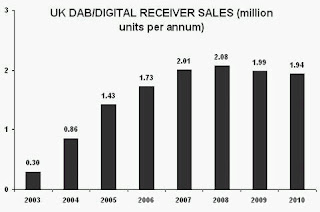

PW: Lindsey Mack, 2015 is supposed to be dependent on, you know, the state of digital [radio listening] and the public’s attitude to it. There’s a report in the papers this week that, in fact, digital sales of digital radio have actually fallen, and fallen for the second year running.

LM: They did fall slightly down last year, compared to the year before but, to be very honest, over the last sort of quarter, the consumer electronic market has been hit very badly. Not just in terms of radio sales, but other consumer electronics as well. You know, the BBC is working very closely with commercial radio and doing a lot of sort of joint promotions. We have to get our messaging right on this.

PW: A lot of our listeners said ‘if it ain’t broke,’ you know, ‘don’t fix it.’ In other words, okay, people quite accept that you’ve got, that you should move on, and that digital probably is the next thing, but why get rid of FM before … in some ways, some people said ‘why get rid of it at all’? Why can’t they exist side by side?

LM: But we’re not getting rid of FM totally. What we’re saying is that the BBC services – the national services – are on FM and DAB, and also we have our digital-only stations on DAB. By 2015, we have to … hopefully, we will have reached 50% digital listening. That’s not [just] DAB. It’s digital listening across all platforms. But there’s a lot that has to be done by, you know, at 2015, and beyond that.

PW: Are you happy about that 2015 date?

LM: 2015 is just … is a date that the industry can focus on. It is not a switchover date. What we have to achieve by then, though, if we can, is obviously digital listening up, we have to have good coverage rollout which has to be robust. People have to be able to turn on their radio and it has to work.

DB: Well, just one final message, Peter, which is that Lindsey’s done a pretty good job at defending the indefensible …

LM: [scoffs]

DB: … and I commend her on it, but don’t get carried away by the anoraks. They’ll tell you anything is working, even if it isn’t.

PW: So what would be your … what’s your solution? What would you want the BBC to do, David?

DB: I’d want them to be absolutely clear and honest and to say: there are problems with this, we’re resolving them, we want people to buy the [DAB] radios because they’ll get the extra coverage of different channels, and we want to keep FM as long as it’s necessary for people to be able to listen to Radio 4 properly.

[thanks to Darryl Pomicter & Luke Shasha]

BBC head of radio: "I'm not going to give you a date" for digital radio switchover

Feedback, BBC Radio 4, 26 November 2010 @ 1330 [excerpt]

Roger Bolton, interviewer [RB]

Tim Davie, director of BBC audio & music [TD]

RB: Tim Davie is the BBC’s director of audio and music. I asked him if the campaign to get decent DAB coverage in 90% of the country by 2015 is still realistic.

TD: I think 2015, and I’ve said it before, is highly ambitious. The BBC would not want to see any [digital radio] switchover unless you had clear evidence of mass listening to digital, and good penetration of digital devices. I think the idea that we force a lot of listeners to a situation where they have to get rid of FM devices and not have something to listen to on digital is clearly not in the interests of the head of BBC radio [laughs].

RB: When would you say, without doubt, we will have digital switchover …

TD: [interrupts] I’m not going to give you a date. I’m not going to give you a date. I’m …

RB: … not ten years, not fifteen years, not twenty years?

TD: I think there will be a switchover. I think it’s been extremely helpful to put a stake in the ground and say ‘could we get to 2015?’ I say that’s ambitious. I quite like ambitious targets. We’ll see how we go.

RB: And there’s concern about coverage. What about quality? Because there are still a lot of our listeners who are not persuaded that the quality [of DAB] is superior, in that digital is actually sometimes worse than FM.

TD: In terms of the areas that are covered by a digital signal, I would be the first to say that we’re not there yet. So, you know, I know some of the listeners out there will say ‘well, I just can’t get a good signal’. Let’s be clear. Before the radio industry would say to people ‘we’re moving away from FM’, we must have full coverage of a DAB signal …

RB: And yet, despite this, you are running a campaign, or rather supporting a campaign, which says ‘digital radio: more to love’ [and] pushing it hard. You’re pushing something …

TD: [interrupts] Absolutely.

RB: … which you have reservations about. TD: When you say ‘reservations’, I don’t think it’s quite the right word. I’m saying we’re building out coverage. I would not endorse a switchover unless coverage were as good as FM. At this point, I think it is utterly appropriate for me, as the BBC head of radio, to say: those people in areas of coverage – and it is important, by the way, when people buy radios, they check that they are in an area of coverage, we absolutely say that repeatedly – but, if they are in an area of coverage, I would absolutely say ‘buy a digital radio’ because you can get Radio 7, the joys of 6 Music, etcetera.

TD: When you say ‘reservations’, I don’t think it’s quite the right word. I’m saying we’re building out coverage. I would not endorse a switchover unless coverage were as good as FM. At this point, I think it is utterly appropriate for me, as the BBC head of radio, to say: those people in areas of coverage – and it is important, by the way, when people buy radios, they check that they are in an area of coverage, we absolutely say that repeatedly – but, if they are in an area of coverage, I would absolutely say ‘buy a digital radio’ because you can get Radio 7, the joys of 6 Music, etcetera.

RB: But, in terms of this campaign, let me quote something said by William Rogers, the UKRD chief executive – part of the commercial radio network. He says it was ‘fundamentally immoral and dishonest to run the campaign, knowing that DAB infrastructure is not good enough, and knowing full well that when people buy a DAB radio, it may not work when they get it home. The BBC should be ashamed of themselves for running this ad. They are telling their listeners to buy something which they know isn’t ready for us yet.’

TD: Well, I mean, it is one voice, and I say ‘one voice’ among many in commercial radio and …

RB: [interrupts] And there are quite a few others who, again, refuse to run the ad.

TD: Absolutely. And, well, I think their beef is, by the way, slightly different to that articulated by William, but it’s really straightforward. 88% of the people in the country can get a signal. If you can’t get a good signal, I wouldn’t recommend digital radio. If you get that coverage, we would absolutely recommend – I think it’s utterly appropriate – to say to people: ‘go and get a digital radio to enjoy the full range of services.’

RB: But the commercial radio sector, or some of it anyway, is saying ‘this is precisely the thing the BBC should be doing. It should be investing and spending so that everybody can get digital coverage.’

TD: Mmm. We’ve said, in the last few weeks, and part of the BBC [Licence Fee] Agreement with the government was to build out national coverage of DAB services. The debate with local radio – just to be clear, and this is a bit complex, so apologies, but – is around the local layer of DAB. And we are negotiating out those costs at the moment. While that negotiation goes on in pretty tough financial circumstances for the BBC, it’s understandable that people say ‘well, we need a bit more clarity.’ I agree with them.

RB: Can I ask you, though, whether the BBC’s enthusiasm for the potential of digital, in terms of stations, is waning. For example, you did propose the closure of 6 Music and the end of the Asian Network, at least as a national station. Are you still in love with digital?

TD: It’s a fair point. The idea around looking at the line-up of stations was never about taking money off the table for digital. We want to keep investing in digital and, I think, in terms of our commitment to digital, this not just about DAB, this is about internet services. We’ve just said, on Radio 3, we’re launching HD sound, which will be a wider signal through internet radio. I think, as the head of BBC radio, I really want to see radio develop into a more competitive marketplace so that it can grow. The idea that the BBC just sits on FM spectrum, and there’s no growth in radio, to me, seems a pretty limited vision of the future for the industry.

RB: So there’s no doubt about the destination, only the amount of time, the speed of getting there?

TD: Radio’s going digital.

Back to the future of radio – the FM band

Help seemed to have arrived for those consumers who are confused by the contradictory messages they are receiving about DAB radio, digital switchover and the future of FM/AM radio. The government created a ‘hot topic’ web page that addresses these issues in the form of a ‘FAQ’. Does it help clarify things?

The government FAQ states:

• “We support 2015 as a target date for digital radio switchover” but, in the next sentence, it says that 2015 is “not the date for digital radio switchover”

• “FM will not be ‘switched off’ … and will continue for as long as it is needed and viable” but then it fails to explain the reason the government is calling it ‘switchover’

• “We believe digital radio has the potential to offer far greater choice and content to listeners” but then it asserts that “quite simply the listener is at the heart of this [switchover] process”

• “11 million DAB sets [have] already [been] sold” but, in the next sentence, it deliberately confuses ‘DAB radio’ with ‘digital radio’ which, it states, “accounts for around a quarter of all radio listening” [DAB accounts for only 16% of all radio listening]

• “Car manufacturers have committed to fit DAB as standard in all new cars by 2013” but it does not explain that only 1% of cars currently have DAB radio

• “Some parts of the country are not served well by DAB” but it then admits that “switchover can only occur when DAB coverage matches [existing] FM [coverage].”

Well, that makes everything crystal clear now. Switchover is not switchover. 2015 is the date but is not the date. It is the government that is insisting upon digital ‘switchover’ but it is a consumer-led process. Almost no cars have DAB now but, in 2+ years’ time, magically they all will. In parts of the UK, DAB reception is rubbish or non-existent, but ‘switchover’ will not happen until somebody spends even more money to make DAB coverage as good as FM … even though FM is already serving consumers perfectly well.

Sorry, what was the point of DAB?

While the UK government ties itself in increasingly tighter knots trying to explain the unexplainable, and to justify the unjustifiable, most of the rest of the world carries on regardless, inhabiting reality rather than a fictional radio future. In May 2010, a meeting in St Petersburg of the European Conference of Postal & Telecommunications Administrations considered the future usage of the FM radio waveband [which it refers to as ‘Band II’] in Europe. Its report stated:

“Band II is currently the de facto analogue radio broadcasting band, due to its excellent combination of coverage, quality and low cost nature both in terms of current networks available and receivers in the market. It is well suited to local, regional and national programming and has been successfully used for over forty years now. FM receivers are part of our daily lives and millions of them populate our households. FM radios are cheap to manufacture and for the car industry FM still represents the most important medium for audio entertainment.”

Its report concluded that:

• “Band II is heavily used in all European countries

• For the current situation the FM services are still considered as satisfactory from the point of sound quality but the lack of frequencies hinders further development

• There are no wide-spread plans or strategies for the introduction of digital broadcasting in Band II

• No defined final switch-off dates are given so far.”

Two paragraphs in the 28-page report seemed to sum up the present UK situation:

“The FM band’s ability to provide high-quality stereo audio, the extremely high levels of receiver penetration and the relative scarcity of spectrum in the band combine to make this frequency band extremely valuable for broadcasters.”

“As FM in Band II is currently, and for the foreseeable future, the broadcasting system supporting the only viable business model for radio (free-to-air) in most European countries, no universal switch-off date for analogue services in Band II can be considered.”

In the UK, we have just seen how “extremely valuable” FM radio licences still are to their owners. Global Radio was prepared to promise DAB heaven and earth to Lord Carter to ensure that a clause guaranteeing automatic renewal of its national Classic FM licence was inserted into the Digital Economy Act 2010. It got what it wanted and therefore avoided a public auction of this licence. Then, when expected to demonstrate its faith in the DAB platform, Global sold off its majority shareholding in the national DAB licence and all its wholly-owned local DAB licences.

Now the boot is on the other foot. Having succeeded in persuading the government to change primary legislation to let it keep commercial radio’s most valuable FM licence for a further seven years, Global Radio has now had to argue to Ofcom that analogue licences will become almost worthless in radio’s digital future. Why? In order to minimise the future Ofcom fee for its Classic FM licence. The duplicity is breathtaking.

When it last reviewed its fee for the Classic FM licence in 2006, Ofcom reduced the price massively because, it explained, it took

“the view that the growth of digital forms of distribution meant that the value associated with what was considered to be the principal right attached to the licence – the privileged access to scarce analogue spectrum – was in decline.”

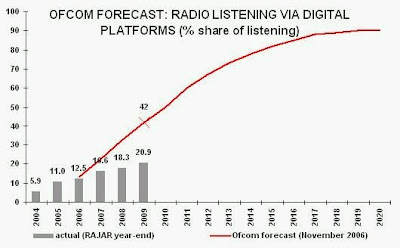

In 2006, Ofcom had published a forecast for the growth of digital radio platforms which has since proven to have been wildly over-optimistic. It had predicted that 42% of listening would be digital by year-end 2009, whereas the outcome was 21%. In 2006, as a result of the steep decline it was forecasting in analogue radio’s usage, Ofcom reduced the cost of Classic FM’s licence fee by 95% from £1,000,000 to £50,000 per annum (an additional levy on the station’s revenues was also reduced from 14% to 6% per annum). The losers were UK taxpayers – the licence fees collected by Ofcom are remitted to the Treasury. The winners were Classic FM’s shareholders, who were gifted a cash cow by Ofcom bureaucrats who misunderstood the radio market.

Fast forward to 2010, and Ofcom is undertaking yet another valuation of how much Classic FM (plus the two national AM commercial stations) will pay during the seven years of its new licence, following the expiry of the current one in September 2011. Has Ofcom apologised for getting its sums so badly wrong in 2006? Of course not. Will it make a more realistic go of it this time around? Well, the signs are not good.

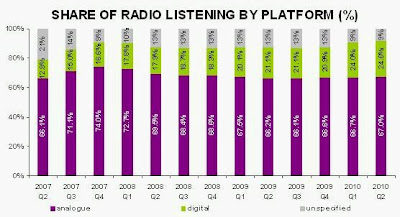

In its consultation document on this issue, Ofcom has repeated the same errors it made in other recent publications about the take-up of digital radio. In Figure 1, Ofcom claims that analogue platforms’ share of all radio listening has fallen from 87% in 2007 to 76% in 2010. This is untrue. As noted in my previous blog entry, listening to analogue radio has remained remarkably static over this time period. Ofcom’s graph has completely ignored the existence of ‘unspecified’ platform listening, the volume of which has varied significantly in different surveys. The graph below plots the actual numbers from industry RAJAR data.

Exactly the same issue impacts the accuracy of Figure 3 in the Ofcom consultation, which purports to show that analogue listening to Classic FM fell from 86% to 72% between 2007 and 2010. Once again, this must be factually wrong. Once again, the volume of ‘unspecified’ listening to Classic FM has simply been ignored and the decline of analogue listening to Classic FM has probably been overstated by Ofcom.

Confusingly, the platform data for Classic FM cited in Figure 3 differ from data in a different Ofcom document [Figure 3.34 on page 33 of The Communications Market 2010] which state that, in Q1 2010, 65% of listening to Classic FM was via analogue, 26% was via digital and 9% was unspecified. In Figure 3, the values for the same quarter are stated as 72%, 28% and 0% respectively. It is impossible for both assertions to be correct.

These inaccuracies have the impact of painting a quite different picture of Classic FM’s transition from analogue to digital listening than the market reality. These matters are not academic. They will have a direct and significant impact on the perceived value of the Classic FM licence over the duration of its next seven-year period. Sensible decisions about the value of the station’s licence cannot be made on the basis of factually inaccurate market data published by Ofcom.

Undeniably, Ofcom is between a rock and a hard place:

• An admittance that, in 2006, Ofcom got its digital radio forecast and its sums badly wrong and, as a result, has already lost the Treasury millions of pounds in radio licence fees, would require humility (and humiliation)

• Not admitting that, in 2006, Ofcom got it wrong would necessitate it to now fix the Classic FM licence fee at the same low rate as in 2006, or even lower, denying the Treasury millions more in lost revenue between 2011 and 2018

• Increasing the cost of Classic FM’s licence fee would be a tacit admittance by Ofcom that its entire DAB ‘future of radio’ policy is simply not becoming reality and that FM spectrum will still remain “extremely valuable for broadcasters”.

In 2006, the low valuation of Classic FM’s licence fee was built upon a top-down bureaucratic strategy which insisted that the UK radio industry was ‘going digital’, whether or not consumers wanted to or not. Now, it is even more evident than it was then that consumers are not taking up DAB radio at a rate that will ever lead to ‘digital switchover’ (whatever that phrase might mean).

However, reading the Ofcom consultation document, it is also evident that the regulator remains wedded to its digital radio policy, however unrealistic:

“We consider that this [Digital Radio] Action Plan is relevant when considering future trends in the amount of digital listening since it represents an ambition on behalf of the industry and Government to increase the amount of digital listening in the next few years.”

In the real world, Classic FM’s owner understands precisely what the international delegations who met in St Petersburg also knew – FM will remain the dominant broadcast platform for radio. Only the UK government and Ofcom seem not to accept this reality, still trying to go their own merry way, while the rest of Europe has already acknowledged at this meeting that:

• The FM band is “extremely valuable for broadcasters”

• The FM band is “currently, and for the foreseeable future, the broadcasting system supporting the only viable business model for radio (free-to-air) in most European countries”

• “No universal switch-off date for analogue services in Band II can be considered.”

[thanks to Eivind Engberg]

DAB radio's slow consumer take-up: lessons not learnt from FM radio 50 years earlier

“Without a knowledge of your history, you cannot determine your destiny”

[…]

Following a UK launch in 1955, the BBC rolled out the FM service relatively quickly: by the end of 1959, most transmitters had been upgraded and 96.4% of the population was within range of the signals; but, even ten years later, when coverage was over 99%, the corporation noted that only one third of households had any form of FM receiver. A similarly slow rise in the popularity of FM continued in the US: although FM services had begun there on the VHF band some ten years earlier than in the UK, it was not until after 1979 that FM finally achieved a higher share of listening than AM.

[…]

[In 1974], [BBC director of engineering James] Redmond expressed puzzlement at the slow adoption of FM, even for fixed reception in the home. Despite its superior sound quality, he noted that ‘changeover has been slower than anticipated.’ …. [One] reason was the simulcasting of radio programmes on FM and on AM, rather than offering new programmes on the new service: listeners would only be able to hear on FM what their AM receivers already gave them.

[…]

This history serves as an illustration of how an apparently self-evidently superior technology pursued as a solution to a problem of audio quality did not automatically find favour with listeners, who […] were apparently prepared to put up with inferior sound and were less inclined to adopt FM while it offered little new programming or competition with television in the evening.

[…]

A mismatch is revealed between the broadcasters’ and engineers’ beliefs as to what was important to listeners, and the preferences and priorities of the vast majority of those listeners themselves.

[…]

[A group of audio enthusiasts] was contrasted [by Wireless World magazine in 1961] with ‘the most important group of all, the reasonable layman’ who simply wants decent reproduction at a reasonable cost, and it is this far larger group that no doubt hesitated to replace perfectly adequate AM receivers with the more expensive FM variety.

[…]

…. early promotion of DAB by the industry certainly used the phrase ‘CD-quality sound’, and placed this and related phrases at the top of the list of DAB’s advantages.

[…]

However, just as the slow pace of adoption of FM confounded broadcasters, for whom its advantages were self-evident, DAB too has failed to gain an enthusiastic embrace from the audience.

[…]

The exhortation ‘radio must go digital’ has been expressed repeatedly over the years: for example, by the Director General of Audio Visual Policy at the European Union’s Media programme, Spyros Papas, in 1998; by BBC Director of Radio, Jenny Abramsky, in 2003; and, more recently, in 2009 by French National Assembly member Patrice Martin-Lalande and, less surprisingly, by Quentin Howard of World DMB. For these commentators, the logic of this transition is self-evident and so needs little explanation, technical or otherwise, and none is offered – put simply, radio cannot remain an analogue technology when all other consumer technologies are digital. Yet, however compelling the logic might be from a technical point of view, the development of both FM and of DAB have failed to follow it: both have emerged only slowly and, in the case of DAB, its future remains uncertain.

[…]

A further difficulty for DAB was the changing landscape of radio in many countries during the period of its development such that, by the time of its public launch in 1995, it was seen by some as reflecting a view of the radio industry that was out of date.

[…]

Just as, by the time FM was launched, other changes in radio had made its introduction more complex, so too we can observe similar, non-technological reasons for the problems in introducing DAB.

[…]

In the case of digital radio, it is possible to identify a number of intentions behind its development, from an imagined need to compete with other emerging technologies to a macro-economic need to aid a key industry. In contrast to the history of radio technology frequently presented as a straightforward series of technical challenges faced and solutions proffered, we find instead that apparently compelling innovations follow a complex path in which cultural practices and economic interests must be taken into account.”

[reprinted with permission of the author]

DENMARK: government contemplates DAB radio’s future

Politicians in Denmark are presently considering what to do about digital terrestrial radio. The next funding period for state radio runs from the beginning of 2011 to the end of 2014 and will have to take into consideration a political decision taken in June 2009 to forge ahead with the migration from analogue radio to the DAB platform. Presently, only state radio stations are available on DAB.

The governing Liberal Party says it “wants to create real competition in the radio market” because state broadcaster Danmarks Radio has “a de facto monopoly over radio in Denmark and so the diversity and choice in radio remains limited.” The party decided in 2009 that it would support FM switch-off as a means to create a “new start” for radio in Denmark. To ensure that DAB will prove an attractive investment proposition for commercial radio, FM would be switched off between 2016 and 2018. The Liberal policy document states:

“An expansion of DAB radio allows for a potentially very large number of different radio channels. This expansion is in full swing in all major European countries, several of which already offer between 60 and 100 digital radio channels, while Denmark currently only offers 20 channels in total. The technological opportunities need to be exploited for the benefit of listeners. And development of DAB also provides the opportunity to create a balanced radio market, where there are real opportunities for development of commercial radio, which has proven not to be possible on the FM band. We should therefore concentrate on the offensive deployment of DAB. England has the full support of all radio operators in the country who decided to work for the switch to DAB in 2015. Recently, France decided that DAB radios must be in all French cars from 2014 and, in March 2009, the German Broadcasting Commission decided to roll out DAB+ in Germany. Although progress has been slow, and in some places has become completely stagnant, there is no longer the same uncertainty that DAB (Eureka147 standard) is the future of radio.”

The Liberal Party document goes on to cite the ‘success’ of DAB in the UK and mistakenly believes that UK government policy is to switch off FM (a fallacy shared by many):

“Today, around 8% of total radio listening [in Denmark] is on DAB. In England, that figure is 12.7% and soaring. To ensure that DAB is an attractive platform for both listeners and investors, it is important that DAB radios are made attractive by adding more unique content. This is the same set of conditions which must be present in other countries that anticipate the same trends. For example, Norway has estimated that at least half of the population must have a DAB radio before [analogue] switch-off can be announced. England will switch to DAB in 2015. Moreover, it is recommended that all cars sold in England from 2013 must be equipped with DAB radios. This decision is backed by both the public service and commercial radio stations. The assumption is that DAB listening will reach 50% in 2015 and coverage will reach 90% of the country and all main roads. Lord Carter’s report ‘Digital Britain’ in January 2009 also defined a set of criteria that must be met in order to close [analogue radio] permanently.”

Ellen Trane Nørby, media spokesperson for the Liberals, said: “Danmarks Radio is proposing that we switch off analogue radio in 2015, but they offer no viable way to get Danes to listen more to DAB.” Nørby believes that the biggest driver for DAB take-up will be when state radio channels are progressively removed from FM: “The people who listen to DAB are heavy listeners to the channels they cannot find anywhere else. If the offerings on DAB are not unique, why would you buy a DAB radio?”

Nørby said that the transition to DAB needs to adopt a realistic timescale: “Today, we are in a situation where most listening takes place on FM and each of us has about five FM radio receivers, compared to only 1.5 million DAB radios [sold in total]. Therefore, it is important that we have a real debate over the future of digital radio, and how we progress safely from FM to DAB. The honest discussion we propose is in contrast to others who say simply that we must switch off [analogue radio] but do not explain how.”

Although the Liberal policy document is resolute about digital radio switchover, Nørby appears more circumspect in interviews. In December 2009, she said: “It is not enough simply to say that FM will be switched off in 2015 without considering a discussion on content. …. Driving the take-up of digital television was the Danish desire to have a flat-screen TV. I have seen no Christmas boom – and we have not seen this for many years – in the sales of DAB radios. That’s why we Liberals have been so critical of the migration plan, because DAB has not won as much grassroots support as you could ask for.”

The government proposals drew a critical response from Michael Christiansen, chairman of Danmarks Radio. He said: “The Liberal Party proposal is a barely disguised attempt to destroy Danmarks Radio’s stations. … The proposal totally disregards modern Danish music by moving the P3 channel over to DAB at a time when it its coverage is not enough. … Replacing P3 [on FM] with a more or less indifferent foreign [commercial] radio channel, I cannot take seriously. We want to help the drive towards DAB, just as we have driven the migration to digital TV. But no one thought of closing down DR1 or DR2 [TV stations] on analogue until digital TV signals were available [to all]. The notion is so far out that I find it hard to relate to.”

European commercial radio trade group says ‘no’ to universal FM switch-off date

At the start of its annual conference held in Brussels on 11/12 February 2010, the Association of European Radios [AER], the trade group representing 4,500+ European commercial radio stations (including RadioCentre members in the UK), issued the following press statement:

“AER considers that setting a date for the switch-off of analogue radio services is currently impossible. Indeed, the question of which kind of technology will be used should be solved first. Hence, broadcasting in FM and AM shall remain the primary means of transmission available for radios in all countries, with the possibility to simulcast in digital technology, until market developments enable a potential time-frame for general digitisation of radio. Transition to any digital broadcasting system should benefit from a long time-frame, unless there is industry agreement at national level to move at a faster rate.”

This statement followed on from a policy paper the Association had published a few days earlier, responding to the European Commission’s Radio Spectrum Policy Group plans for its draft Work Programme. The paper said, in part:

“It should be underlined that, in most of Europe, currently and for the foreseeable future, there is only one viable business model: free-to-air FM broadcasting on Band II. Thus, Band II is the frequency range between 87.5-108 MHz and only represents 20.5 MHz. Across Europe, nearly every single frequency is used in this bandwidth. Thanks to the broad receiver penetration and the very high usage by the listeners, this small bandwidth is very efficiently used. On-air or internet-based commercially-funded digital radio has indeed not yet achieved widespread take up across European territories. These two means of transmission will be part of the patchwork of transmission techniques for commercially-funded radios in the future, but it is hard to foresee when.

So no universal switch-off date for analogue broadcasting services can currently be envisaged and decision on standards to be used for digital radio broadcasting should be left to the industry on a country-by-country basis.

Radio’s audience is first and foremost local or regional. Moreover, spectrum is currently efficiently managed by European states and this should remain the case: national radio frequency landscapes and national radio broadcasting markets are different, with divergent plans for digitization, diverse social, cultural and historical characteristics and with distinct market structures and needs…..”

“Finally, AER would like to recall that European radios can only broadcast programmes free of charge to millions of European citizens, thanks to the revenues they collect by means of advertising. These revenues are decreasing all through Europe due to two factors: the shift towards internet-based advertising, and the recent financial crisis. For 2009, radio advertising market shares were forecast to decrease by 3 to 20% all across Europe, compared to 2008.

In some countries (e.g. France and the UK), a part of the revenues derived from the TV digital switchover was supposed to be allocated to the support of digitisation schemes for radio. This is no longer the case. In most countries, it is still unclear who will bear the costs of the digitisation process.

However, any shift towards digital radio broadcasting entails very long-lasting and burdensome investments. Nevertheless, some individual nations may wish to proceed with a move to greater digital broadcasting at a faster rate, as there will be no ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach.

So, any shift towards digital radio broadcasting will most likely require a very long process. Decision on the adequate time-frame should be left to each national industry: as a matter of principle, transition to any improved digital broadcasting system should benefit from a long time-frame, unless there is industry agreement to move at a faster rate.

It should also be recalled that commercially-funded radios are SMEs, and are in no position to compete for access to spectrum with other market players. So, market-based approaches to spectrum (such as service neutrality or secondary trading) should not be enforced in bands where commercially-funded radios broadcast or may broadcast.

To end up with, AER would like to recall that, in most of Europe, currently and for the foreseeable future, there is only one viable business model: free-to-air FM broadcasting on Band II; hence:

• no universal switch-off date for analogue broadcasting services can currently be envisaged

• now and for a foreseeable future, commercially-funded radios need guaranteed access to spectrum, in all bands described above. Besides, no further change to the GE 84 plan [the 1984 Geneva FM radio broadcast frequencies agreement] should be suggested, but the plan should be applied with consideration to the technological development (and its enlarged scope of possibilities) throughout the past 25 years

• any shift towards digital radio broadcasting should benefit from a long and adequate time-frame.”

NORWAY: every fifth radio sold is an internet radio, every eleventh is DAB

In Norway, sales of internet radio receivers are booming. During the final quarter of 2009, 22% of radios sold were internet radios, up from only 1% a year earlier, according to Norwegian website Sandnesavisen. By comparison, only 66,000 DAB radios were sold in 2009, 9% of the total 729,000 radios sold during the period, according to data from the Electronics Industry Foundation. Additionally, 200,000 mobile phones were sold in Norway during 2009, none with DAB capability but many with integrated FM radios.

Erik Andersen, information officer for the Electronics Industry Foundation, said: “We estimate that there are somewhere between 12 and 15 million FM radios that are in regular use around the country while, in comparison, only approximately 290,000 DAB radios have been sold in recent years.”

Andersen is not surprised by the rather low DAB radio sales, and finds it problematic that a date for FM band switch-off has not been announced which could be referred to. “We have no desire to mislead customers so, as long as politicians do not give us a switch-off plan, we advise enquiring customers to buy an FM radio,” said Andersen.

Jarle Ruud, acting general manager of Digitalradio Norge, the organisation charged with ensuring a speedy and smooth transition from analogue to digital radio in Norway, said: “This is a classic ‘chicken and egg’ situation, both in terms of sales volumes versus a switch-off date, and the channel selection on DAB.” Just as consumers are hesitating to buy a DAB radio before the government announces a switch-off date, Ruud thinks there are many radio stations that refuse to invest in digital transmission equipment because of the potentially lengthy and costly period of dual distribution.

The sales trend came as no surprise to Øyvind Vasaasen, media manager at NRK (state broadcasting) and chairman of Digitalradio Norge, who said: “This is what we predicted. We have remarked to the authorities that sales appears to have stabilised at around 60,000 DAB radios sold per year, and this is also the result for 2009. It shows that the sales trend is far too slow.”

Geir Friberg is managing director of Norway’s largest local radio group, Jærradiogruppen, which owns more than 20 of the approximately 150 local stations in Norway. He said: “There is really no great difference between FM and DAB. There are too few radio stations that broadcast on DAB today, and listeners cannot hear the difference between FM and DAB.” Friberg believes that adding more FM stations may even be a better policy than DAB.

Per Morten Hoff, general secretary of IKT Norge (Norway’s IT industry interest group), queried the accuracy of the published sales figures: “More and more consumers have eyes for internet radios, and the Norwegian company TT-Micro has alone sold 20,000 web radios. Since these radios can also receive FM, DAB and 13,000 internet stations, they are strangely classified as ‘DAB radios’ in the statistics. This is apparently to show that DAB is not a total failure. The true DAB sales are probably no higher than 40,000 units, and that figure is getting smaller. There is also the riddle that sales of mini-TV’s are included in the sales statistics of DAB radios.”

Jørn Jensen, president of World DMB Forum, responded: “Hoff does not know what he’s talking about. Radio broadcasting on DAB and DAB+, as well as mini-TV’s in DMB, all use DAB technology.”

At the beginning of February 2010, the Norwegian media regulator, Medietilsynet, submitted a 145-page document to the government on the digitisation of radio broadcasting. This is in preparation for a White Paper on digital radio that will be published by the government during 2010. The report was commissioned to map the Norwegian local radio industry’s opinions on the migration to digital radio and how it could be achieved. It collated responses from 55 parties and it concluded:

“The results of the survey reveal that virtually all local radio licensees believe that the digitisation of local radio will have economic consequences for them as businesses. The players fear that a transition will be so costly that only a few of the current licensees will survive digitisation. The consequence may be that ownership diversity disappears and that the market is left with big group operators. Besides mentioning competence-building, information and predictability, the majority of licensees believe that the most important measure the government can contribute to the digitising process is financial support in one form or another.

Local radio licensees who participated in the survey are roughly evenly split down the middle on their view of whether local radio should be digitised or not. Those who are negative to digitisation weigh the economic aspect heavily. When asked what distribution platform they see for themselves as the primary platform for local radio in the future, 52 percent responded analogue broadcasting via the FM band, 33 percent broadcasting via a digital platform such as DAB, DRM, etc and 9 percent broadcasting via the internet……”

“Amongst local radio licensees, 78 percent are negative about a switch-off date for analogue local radio broadcasting. 18 percent are positive about a switch-off date.”

Vigleik Brekke, chairman of the Norwegian Association of Local Radio (NLR) said that there was no economic reason for many of his 150 member stations to migrate to digital transmission. “Closing FM radio will create problems for stations,” he said. “They will not be able to survive.”

Professor Lars Nyre of the University of Bergen’s Institute of Media Studies said he was sceptical about DAB, especially as FM radio seemed to be perfect for listeners.

Asked whether the government’s White Paper will include a switchover date, Norwegian Culture Minister Roger Solheim said: “This is an important issue, and we aim to present the facts in 2010. One of the key questions we want to work with in the White Paper is whether we should fix a switch-off date.” Asked if his predecessor Trond Giske’s policy still held sway that half of Norway’s households should own a digital radio before a switch-off date is announced, Solheim said: “It is certain that digital radio will come, we see that too, in the developments. The question of the timing, and the state’s role in it, we must come back to in the White Paper.”

According to industry data, one in three households in Norway buy a new radio each year. Each household owns between 6 and 7 radios.