When you are looking for an exit route from a product you have been developing for nearly two decades, and which has consumed hundreds of millions of pounds, you need to find a damn good reason that will deflect the blame elsewhere. You need a report, an organisation or some bona fide research that screams out ‘no’ at the highest volume. Then your response can be: “I would be a fool to ignore the warning signs voiced by X” when what you are really saying is: “Blame them, not me! It’s them that made me do it.”

DAB radio and digital radio switchover presently seem to be at this point. But there is a big problem for a radio industry that is belatedly trying to find a way ‘out’. Almost all previous reports produced by the government, the regulator, the radio industry, the electronics industry, the working groups, Digital Britain and the car manufacturers have been overwhelmingly positive about DAB and have painted an amazingly rosy future. There has been almost nothing published about DAB by agencies of the state that has said plainly: “Stop this crazy plan.”

So whose fault can it be that DAB radio and digital switchover has not worked? Given the sheer number of agencies that have been so gung-ho for so long about DAB, the fickle finger of fate naturally had to point elsewhere and so it landed upon ‘the consumer’. It becomes much easier to decide that the general public is the reason for a masterplan’s lack of success when everybody sat around the government’s conference table is feeling a little guilty about their shared role in a wasted £1bn investment.

A change of regime is always a useful point at which to invoke such a change. In July 2009, less than a year into his first radio job, the BBC’s top radio manager Tim Davie explained that digital radio switchover would be determined by listeners, not by the BBC:

“From a BBC perspective, whether it be ‘Feedback’ or our constant audience research, the idea that we would move to formally engaging switchover without talking to listeners, getting listener satisfaction numbers, all the various things we do, would be not our plan in any way. We would be – we are – in dialogue now for the next six years. … I think we are pretty committed to digital. Having said that, since I have arrived at the BBC, I certainly haven’t seen it as inevitable that we move to DAB.”

The following month, BBC Trust chairman Sir Michael Lyons reinforced this notion:

“Who comes first in this? Audiences and the people who pay the Licence Fee. It is an extraordinarily ambitious suggestion, as colleagues have referred to, that by 2015 we will all be ready for this. So you can’t move faster than the British public want you to move on any issue.”

The change of government then provided an opportunity for the Department for Culture, Media & Sport [DCMS] to similarly invoke the will of the people in determining digital radio switchover. In July 2010, culture minister Ed Vaizey said:

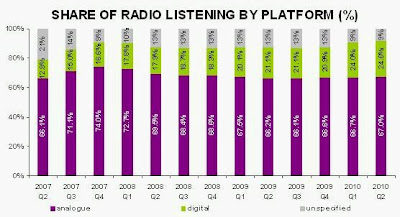

“If, and it is a big if, the consumer is ready, we will support a 2015 switchover date. But, as I have already said, it is the consumer, through their listening habits and purchasing decisions, who will ultimately determine the case for switchover.” [emphasis added]

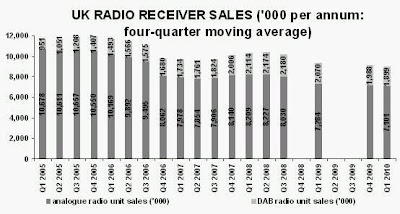

For both the BBC and the government, the problem with belatedly putting the consumer at the centre of digital radio switchover is that almost no organisation, over the course of a decade of DAB, has done any significant consumer research about DAB. Why? Because the implementation of DAB radio in the UK had always been a top-down policy initiative by civil servants, regulators, trade organisations and commercial opportunists, without ‘the man on the Clapham omnibus’ having ever been consulted.

There was one notable exception. When the government’s Digital Radio Working Group considered the issue of DAB radio switchover during 2007/8, a sub-committee named the Consumer Impact Group had prepared a report. However, this report was not made public until almost a year after the Working Group had been wound up. The report had been highly critical that consumers’ viewpoints were not being considered:

“The group is concerned that the case for digital [radio] migration has not been made clearly enough from the point of view of the consumer. While it is clear what the rationale is for the radio industry, the group would like to see a compelling argument as to why digital migration is desirable for consumers and what its benefits would be for consumers.”

But that was then, this is now. Then, digital radio was considered by the previous government to be a real possibility, and that is why dissent from consumer groups was buried. Now, that same consumer dissent could provide the perfect nail on which to hang any number of DAB exit strategies. A new report outlining the massive consumer challenge of digital radio switchover would be a perfect ‘get out of jail free’ card for many long-term DAB stakeholders.

So today, a new report has been published by the government’s Consumer Expert Group [CEG] which asks the pertinent question ‘Digital radio switchover: what is in it for consumers?’ Moreover, rather than it being embarrassedly added to the depths of the DCMS web site a year later, today’s report was circulated to the press and stakeholders in advance of publication. Its introduction states:

“This report was not requested by Government but the CEG have taken the initiative to attain a thorough understanding of the consumer issues surrounding digital radio and bring them to the Government’s attention as preliminary policy decisions are made.”

In other words, this new report just happens to directly address the “big if” cited in the culture minister’s speech about digital radio switchover nine weeks earlier. If its publication were not startling enough, its conclusions are damning in almost every respect about the lack of progress made to date with digital radio switchover. But, before that, the report is quick to invoke the role of consumers in what it admits is “new” government policy:

“Setting a date, or a firm commitment to a date, would have had the effect of scaring consumers to switch. Clearly this would not be compatible with Government policy to support a switchover when enough listeners voluntarily adopt digital radio. Government’s new emphasis on consumers should provide the focus to ensure consumer concerns and needs regarding digital radio are addressed, thereby reducing the barriers to voluntary take-up.”

However, if these “consumer concerns and needs” were to prove simply too onerous and costly for the government to address in the current economic climate, the choice is now there to opt out of pursuing the DAB switchover policy altogether. The Film Council … the Audit Commission … DAB radio switchover. Chop chop chop. The first two might have seemed a bit arbitrary to voters. Now, at least this one has a consumer report to back it up.

So this new report reiterates and elaborates the same arguments made in the previous consumer report to the Digital Radio Working Group two years earlier, and adds some more. Its recommendations are worth quoting in full:

“The consumer costs and consumer benefits of digital radio

• A full cost benefit analysis from a user perspective must be carried out as a matter of urgency;

• Consumer benefits need to be clear and demonstrable before an announcement for a digital switchover is made;

• A workable system for the disposing and recycling analogue radios, which consumers are likely to implement must be introduced;

• Emphasis should not be placed on driving down costs unless the sound quality and functionality of cheaper DAB sets are at least equal to analogue;

• There must be more emphasis on improving the basic usability, rather than the advanced functionality, of digital radio to encourage take-up;

• Both the BBC and the commercial sector need to offer new and compelling digital content to convince consumers to adopt digital radio;

• Research into consumers’ willingness to pay and into their concerns and needs relating to digital radio needs to be carried out as a matter of urgency.

Take-up

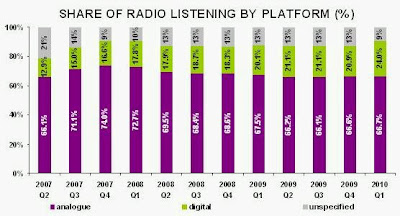

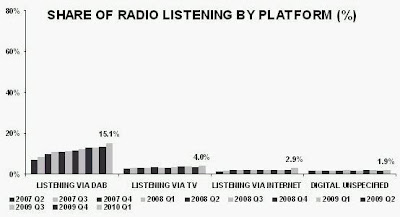

• The take-up criterion should compare like-for-like listening platforms and measure DAB listening only;

• A digital switchover date should only be announced when no more than 30 per cent of listening remains on analogue;

• The target date for a digital switchover should be revised upwards as 2015 is realistically far too early for the necessary preparations to be put in place for consumers. Any target date set should be looked upon as secondary to consumer issues such as willingness to adopt the technology, voluntary take-up and digital radio reception as an instigator for switchover;

• Measures need to be taken to introduce a more inclusive methodology for measuring take-up.

Coverage

• The fair allocation of coverage build-out costs between the BBC and the commercial sector must be made once build-out plans are agreed;

• The coverage criterion should be measured by signal strength, not just population, so that indoor and mobile reception are considered;

• The coverage criterion must be geographically weighted to ensure rural communities are not left behind;

• The switchover roadmap must include plans for DAB+;

• DAB+ compatible chips must be installed as standard to “future-proof” receivers as a matter of urgency;

• The reception time delay between receivers should be standardised.

Vehicles

• A Digital Radio Switchover date cannot be announced until DAB radios have been standard in vehicles for a minimum of 2 years, in other words by 2015 at the earliest;

• An affordable in-vehicle converter needs to be developed urgently which works with a vehicle’s external aerial, is safe, easy to fit and aesthetically pleasing;

• A switchover date cannot be announced until there is a solution to in-vehicle conversions, providing the majority of motorists with the opportunity to have a digital radio in their vehicle;

• A solution for the continuation of traffic and travel services on FM for a transitional period following digital switchover needs to be agreed;

• An accreditation scheme for dealers and other installers of retrofit digital devices must be developed.

Accessibility

• Digital switchover should not go ahead without suitable equipment being available for all listeners including older and disabled people;

• Digital radios which incorporate voice output technology must be available for blind and partially-sighted people preferably via the mainstream market or, if that is not feasible, through a channel made affordable by Government intervention, such as a help scheme;

• Appropriate information and support on the enhanced features of accessible digital radios should be available from retailers;

• Appropriate usability requirements should be included in minimum receiver specifications and a kitemarking scheme;

• The proposed integrated station guide must be consumer tested before any decision on its inclusion in devices is made.

Consumer information

• A clear and balanced public information campaign needs to be implemented through a trusted body, independent of the industry;

• Once a switchover date is announced, sales of analogue-only radio must stop;

• A post-announcement information campaign to target vulnerable groups should be developed;

• The digital tick should be adopted for digital radio and adapted as necessary;

• A ‘scorecard’ should be displayed on all products to convey more information about the available features at the point of sale;

• A digital radio pre-purchase checklist should be widely available and at point of sale;

• An effective training and “accredited adviser” scheme needs to be developed for retailers;

• The CEG must be involved in the minimum specification for digital radio;

• The CEG must be involved in the design and development of any public information campaigns.

Consumer support and a help scheme

• Any Digital Radio Switchover must be accompanied by a help scheme to assist those who would find it disproportionately difficult to switch;

• The eligibility criteria of a help scheme should include people registered blind or partially sighted, those on low incomes, the over 65s and those with learning disabilities and other cognitive difficulties such as Alzheimer patients;

• A help scheme for digital radio should provide appropriate accessible equipment and include as many instructional home visits as necessary;

• A help scheme should be publicised early on in the information process on a national level and the publicity should coincide with the start of the national information campaign for a switchover;

• The CEG must be consulted in the preparation of printed material and publicity on the help and support available;

• The engagement of the voluntary sector in providing assistance with a digital radio switchover should be properly supported and funded;

• Government should ensure that charities, such as Wireless for the Blind Fund and W4B, are not undermined financially or strategically by a help scheme or any of its components, as these charities will be left with providing the ongoing of support, assistance and help people need once a help scheme has finished.”

These recommendations seem to divide into: those that would require considerable time to implement, those that would require considerable money to implement, those that would require both time and money, and those that would be almost impossible to implement. Such recommendations should have been considered and acted upon before DAB transmitters even started to be built-out in the 1990s. Their presence in 2010 only serves to highlight the ineptitude of the 1990s ‘plan’.

No organisation escapes unscathed from the critique of the Consumer Expert Group (some are not named): BBC radio, commercial radio, Ofcom, RadioCentre, receiver manufacturers, the Digital Radio Development Bureau, Digital Radio UK, etc. By spreading the criticism so widely, no single stakeholder gets to feel singled out or isolated for DAB’s failure.

Now it is left to the government to decide to pull down the shutters on DAB radio switchover. That will not require the immediate death of DAB. But it will provide the BBC with something that it can sacrifice down the line to budget cuts in the assault on its Licence Fee. For commercial radio, it will provide relief from expensive dual transmission costs, once a settlement has allowed it to keep its coveted licence renewals invoked by this year’s Digital Economy Act. For consumers, it will offer certainty that FM radios will continue to work. There will be sighs of relief all around.

I started writing about DAB radio as a news editor in 1992 and today’s report is the first government distributed document I have seen that sensibly articulates the multitude of barriers and obstacles to digital radio switchover happening in the UK. The very first words of the report summarise the current situation perfectly:

“Despite the introduction of digital radio in the UK in 1998, analogue radio is still a key feature in many households.”

Now we await the fat lady.