Apologies: this is an extremely long blog entry. I suggest it is worth persevering with because, more than any other ministerial statement, the transcript below illustrates perfectly the government’s mistaken determination to press ahead with its policy to adopt DAB radio. During the weeks it has been sitting, the House of Lords Communications Committee has become increasingly adept at understanding the flaws and contradictions in the Digital Economy Bill’s radio clauses, which is why their dialogue here with the Minister crackles with suspicion.

Siôn Simon handles his government script with the aplomb of a dodgy used car salesman, combined with the smug self-satisfaction of a schoolboy who can proffer a verbal comeback to any question asked of him. In December 2009, Simon had to repay £20,000 in parliamentary expenses for a second home he was renting from his sister between 2003 and 2007. Embarrassingly, the Broadcasting Minister reveals here his mistaken belief that the government’s proposed 2015 digital radio switchover date is written into the Digital Economy Bill. It isn’t.

I could itemise the many flaws in the Minister’s replies to the Committee’s questions, but it would spoil your reading fun. Your starter for ten – Halfords does not stock DAB radios.

House of Lords

Select Committee on Communications

“Digital Switchover of Television and Radio In The UK”

10 February 2010 [excerpt]

Witnesses:

Mr Siôn Simon, a Member of the House of Commons, Minister of State for Creative Industries

Mr Keith Smith, Deputy Director, Media in the UK, Department for Culture, Media and Sport

Chairman: Good morning. Thank you very much for coming, you are very welcome to the Committee. Now, Mr Simon, you are the Broadcasting Minister.

Mr Simon: For the moment, until the end of today.

Chairman: Well, that is what I was going to raise with you. How long have you been in this post?

Mr Simon: I have been in this post since, I think, the beginning of June last year and today is my last day, so this will be my final appearance before a Select Committee and I am looking forward to it tremendously.

Chairman: Well, before you look forward to it too immensely, let me ask you a question, and I ask the question because, on my reckoning, there have now been five broadcasting ministers since May 2006. That is a very high turnover. Do you think that these frequent changes help in making policy?

Mr Simon: I think I should have been appointed in 2005, but —-

Chairman: But Number Ten actually omitted to do so?

Mr Simon: They omitted to do so and, as you know, you will have to ask the Prime Minister about the appointment of ministers because that is his decision, not mine.

Chairman: Well, the resignation of ministers, on the other hand, is very much in the hands of ministers, is it not? You are not even going to take the Digital Economy Bill through?

Mr Simon: I have had great enjoyment and satisfaction dealing with it as it has been through all the various stages of consultation with stakeholders across industry and Parliament since I inherited the White Paper. The White Paper was published the week I was appointed, the Digital Britain White Paper.

Chairman: By your predecessor who also only lasted a year.

Mr Simon: I think he did an outstanding job actually, I must say. Having come in and inherited his output, I think Lord Carter did a very, very sophisticated, subtle and impressive job across a whole range of industry sectors.

Chairman: At any rate, you enjoyed it so much that you are not going to stay for a couple of months?

Mr Simon: It has been an absolutely tremendous pleasure and privilege. I think it is one of the best jobs in Government. I have lots of reasons that I am stepping down as I am deciding to do other things and I am also stepping down from Parliament.

Chairman: What are the other things you are going to do?

Mr Simon: I am going to run, if I can, to be the first elected Mayor of Birmingham, which will probably be a couple of years, but is a job worth doing and worth planning for.

Chairman: Well, as a Birmingham MP for 27 years, I am probably the person round this Committee who has most sympathy with that ambition, although I do not think the job actually exists, let alone you are going to win it. Quite seriously, do you really think that these swift changeovers of ministers actually do the policy process any advantage?

Mr Simon: I do seriously have to tell you that I am a junior minister and junior ministers, as you know with all your experience, are not responsible for the appointment of ministers, the policy towards the appointment of ministers or the length of tenure of ministers. You need to take that up with the Prime Minister; it is not a matter for me.

Chairman: Well, I doubt very much whether the Prime Minister is going to agree to come to this Committee, given all the other things he has got on his mind just at this period in Government, but never mind.

Lord Maxton: Do we know who your successor is going to be?

Mr Simon: I do not know.

Lord Maxton: Presumably, somebody will have to be appointed this afternoon if you are going this afternoon?

Mr Simon: Again, it is a matter for Downing Street, not for me or officials.

Chairman: So you are going this evening and we do not know who is going to take your place?

Mr Simon: I think it is fairly common procedure that it is after the one minister has resigned that the next one is appointed, so I assume there will be an announcement from the Prime Minister in due course about what arrangements will need to be made.

Chairman: Okay, I do not think we are going to get much further on this particular path. Let us ask you about the digital switchover. This is a short inquiry that we have conducted and most complaint, I think, has been about radio. There seems to be enormous uncertainty amongst the public about what is happening and indeed what the case for radio switchover is. We have just been talking to consumer groups and, just to give you some flavour of what they said initially, one said he could not see any advantage, another said it was difficult to see what the benefits are and a third said that they were concerned about the expense of throwing away sets, and I think that is one of the issues that has come through from some of our correspondence as well. What would you say are the advantages of digital switchover as far as radio is concerned?

Mr Simon: I think there are several advantages. Firstly, digital has practical and technical advantages of benefit to the consumer, so there is a whole range of extra functionality and interactivity that you get from a digital radio set that you will not from analogue. It is also the case that the FM infrastructure, the transmission infrastructure of FM, is ageing, FM is an old analogue technology, and the likelihood is that in the medium term the question will arise anyway of whether this infrastructure can economically be renewed and the likelihood is that it probably would not be economic to renew this infrastructure. What you would be faced with in that case would be a piecemeal disintegration of the FM infrastructure in a disorderly way and an inevitable move by the market towards digital. What the Government is, therefore, doing is trying to help manage this move in an orderly and efficient way.

Chairman: So what would you say to the member of the public who has written a not untypical letter to us in which he said, “We have acquired a large number of FM radios over the years, all of which work perfectly. Five of these are used regularly in different rooms. Why should we ditch these for no good reason?”?

Mr Simon: Well, firstly, they will not necessarily have to ditch them; it will depend what services they are using them to listen to, and it may be that there are different members of the family using different sets in different rooms at different times to listen to different services. It is reasonable to assume, therefore, that in a typical family some of those sets in some of those rooms will be used to listen to the kinds of local commercial services or community radio services which will remain on FM, indeed which will be expanded and have their presence secured on FM and remain available. Now, clearly it will be the case that, in order to listen to major national or large regional broadcasters after 2015, consumers will need some kind of upgrade to listen to digital. It is very likely that a relatively cheap, small add-on which converts an analogue set to a digital set will become available before the switchover date. We are talking to manufacturers, and I cannot guarantee what manufacturers will manufacture, but we think it very likely that a small, cheap converter will be available and people will purchase over time new sets.

Chairman: Well, we will come to that point. Can I just ask one broader point though than that. Ofcom commissioned a cost-benefit analysis of digital radio migration from Price Waterhouse. That report found that the benefits might outweigh the costs only after 2026. Is that the basis upon which you are planning as well?

Mr Simon: I think that the report that Ofcom commissioned was into the recommendations of the Digital Radio Working Group, which were different from those which eventually made it into the Digital Britain White Paper and the Digital Economy Bill, so, to be honest, it is not really a straight comparison because the Price Waterhouse report was not into what is going to happen, it was into a different set of recommendations by a different group.

Chairman: I hear what you say, but why has the Price Waterhouse report not been made public?

Mr Simon: Clearly, there has been a little bit of difficulty about this. There is no sense at all in which it was intended not to be made public. It is now on the DCMS website. It should have been on the DCMS —-

Chairman: In a redacted, blacked-out form.

Mr Simon: I believe that the form that it is in on the website is redacted to remove commercially sensitive information, which is the usual practice with commercially sensitive information, but I am told that the Committee has been supplied with an unredacted version by Ofcom, and any stakeholders who have asked for a copy have been sent a copy. We should have put it on the website more quickly. There were technical difficulties to do with the report not having been written internally and being supplied in the wrong format and so on which meant that it did not get on the website. There has been no intent whatsoever, and there is no intention, to keep private the report.

Chairman: Well, we, I gather, have received the report this very morning, so we obviously have not looked through it yet

Lord St John of Bletso: I noticed in the written evidence from DCMS that one of the challenges of the digital radio switchover will be converting the occasional radio listener rather than the avid listener who has already invested in DAB sets. There has been also a commitment to a further cost-benefit analysis of the digital radio upgrade. What is the timetable of this proposed new cost-benefit analysis, and will you wait for the outcome of this analysis before taking further decisions to go forward?

Mr Simon: I think the commitment with the digital radio upgrade is for a full impact assessment and a cost-benefit analysis particularly of the need for, the case for and the design of a possible digital radio help scheme. As to the sense in which there is a cost-benefit analysis of the whole programme, rather than a kind of discrete piece of commissioned work, like the report we were just talking about, this would be a constant, ongoing process of review which is starting this year and will be constantly reviewed, measured and updated as the programme unfolds.

Lord St John of Bletso: We have, as I understand it, 90 per cent still on analogue and ten per cent on digital, but have you estimated the effects of the costs and revenues to the different radio stations and the bodies arising out of digital migration, and how will profitability change and who will benefit? That is really what we are trying to get at.

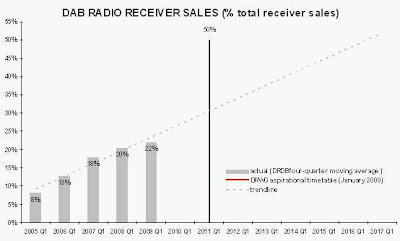

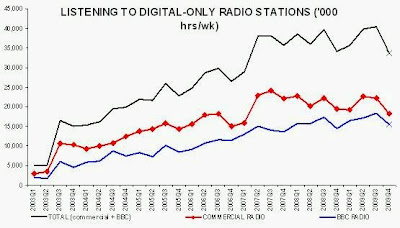

Mr Simon: I think the percentage already listening on digital is higher than that, I think it is more like 20 per cent, and we are committed to not switching over until listenership on digital is at least 50 per cent and coverage is at least comparable to FM, which would be 98.5 per cent. Can you just tell me a bit more as I was not quite sure exactly what you wanted in your subsequent question?

Lord St John of Bletso: It was just the phasing of the transfer as far as not just the timing of the cost-benefit analysis, but what the effects would be and the costs and revenues for the different radio stations and others.

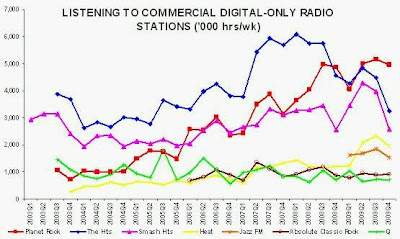

Mr Simon: The intention is that the radio market be much more distinctly than it currently is organised into three distinct tiers, so a national tier at the top, which would be digital, a large regional tier, which would also be digital, and then at the lowest end a local tier, which would be small, local commercial broadcasters and community radio stations who would remain on FM. The effect would be that some currently medium-small commercial broadcasters would probably grow their broadcast areas and migrate on to digital. Some of that size could potentially shrink slightly and stay on FM, the underlying dynamic being that it is much cheaper to stay on FM than go on to digital, and there would be small commercial broadcasters for whom it would not be economic to migrate to digital which has inherently a much bigger footprint.

Lord Maxton: I am not quite clear where the BBC would fit into that because they provide national and local services.

Mr Simon: If I may say so, my Lord, that is a very good question and the answer is that in the crucial matter of building out extra transmitter infrastructure so that the coverage of digital matches by 2015 the current coverage of FM, which is about 98.5 per cent of the country, the assumption is that the commercial sector and commercial operators would fund that build-out as far as it was commercially and economically viable, and then the assumption is that the BBC, with its obligation to provide a universal service, would fund the probably seven or eight per cent of the build-out which was not commercially viable.

Lord Maxton: But they were only talking about 90 per cent, the BBC were last week.

Chairman: Is it going from 90 to nearly 100 per cent?

Mr Simon: Very roughly. It is between 90 and 98.5 which, it is assumed, would not be commercially viable.

Chairman: But you are assuming that the cost of that will be taken from the licence fee?

Mr Simon: I am assuming that the BBC would be building those transmitters. We are talking about a cost of probably between £10-20 million a year.

Chairman: So it would be taken from the licence fee?

Mr Simon: I think the assumption is that the BBC would be able to absorb that within its current budgets.

Chairman: Well, the BBC said to us that actually they would like to talk to you about the licence fee, so there may be a constructive dialogue to be had there!

Lord Maxton: Obviously, what you are saying does imply a fairly major restructuring of the radio industry. I assume you are going to be consulting on this, are you?

Mr Simon: We are, and have been, consulting continuously. I have had two summits with small commercial operators who, at the beginning of the process of talking to them, were a bit concerned.

Lord Maxton: Can I link this to one of the Government’s other quite right policies, which is extending broadband to everybody. Where does that fit into radio because it seems to me that people are already selling internet-available radios so that you can pick up radio stations from wherever?

Mr Simon: It is all part of the same, I think, pretty relentless drive towards digital, but they are different strands of the same broad movement rather than being directly interlinked or dependent, so internet radio listenership forms part of the digital radio listenership, but it actually forms a very small part of the digital radio listenership and there is still a case and a clear need for an explicitly transmitted-over-the-airwaves radio digital output as well; you

cannot do it all on the internet.

Baroness McIntosh of Hudnall: I just wanted to go back to two things that you said in your last couple of answers, Minister, and the first one was about the 50 per cent target for digital listenership before making the decision to migrate to digital. We had evidence from the witnesses who were here immediately before you that there is a strong likelihood that the 50 per cent of people who, at that point, would not have taken up the digital option may include a high proportion of vulnerable listeners. Do you have any observations, or indeed has your Department done any research, to demonstrate whether or not that is likely to be the case? Also, you made the point about the BBC becoming responsible for making up the shortfall between 90 and 98.5 per cent, and the evidence that they gave us last week demonstrated, or they believe it demonstrates, that the level of investment to produce that last eight to ten per cent’s worth of coverage is enormously much greater than the level of investment that has been necessary, or will be necessary, to arrive at 90 per cent. I think, from memory, they were talking about having 90 transmitters currently and needing to invest in a further 140 in order to meet that remaining ten per cent. That is a pretty big ask, and I just wonder whether you would, in the light of that, be prepared to reconsider your answer to Lord Fowler about where the money is going to come from.

Mr Simon: If I could take those two, in the first case we have not commissioned research about that yet. Intuitively, I suspect that you are probably right and that there will be a disproportionately high number of, for instance, older, disabled or other vulnerable people in the cohort that is not digital by the time we switch over, so, for that reason, we will be commissioning a full impact assessment and cost-benefit analysis, looking into exactly those issues and using that information to determine, and what would be the details of, some kind of digital switchover help scheme in just the same way that we commissioned research which informed the digital TV switchover Help Scheme that we have ultimately put into place and which is, I think, widely held to have been pretty successful. On the second question, we have been talking to the BBC very closely and very recently about this and, no, I am pretty clear that what I said initially was right, that we are talking about costs of somewhere between £10-£20 million.

Baroness McIntosh of Hudnall: Sorry, £10-20 million per annum, you said earlier?

Mr Simon: Per annum, yes.

Baroness McIntosh of Hudnall: Over what period? An additional net £10-20 million spend for the BBC into an indefinite future or over a specified period of time?

Mr Simon: No, over the period of the switchover, after which the BBC’s costs would decline by up to £40 million a year because they will only be transmitting on one platform and the cost of analogue will be deleted. The basic principle is that the market will pay the cost as far as it is viable. For those people who live in areas, presumably almost always more rural areas, where it is not commercially viable to build out digital transmitters, then the BBC, because it has in its Charter an obligation to provide a universal service, will likely be bound to build out those transmitters. In our conversations with them, they have recently seemed to recognise that and I certainly have not had a sense from them that they believe that the cost would be prohibitive.

Chairman: I am bound to say, it is not the flavour of the evidence that they gave to us last week. I think Lady McIntosh makes an extremely good point here. Rather than continuing this, we had better just recheck with the BBC what exactly it is that they want and require here, but, I have to say, your evidence is slightly at variance with what the BBC were telling us.

Baroness Howe of Idlicote: I think quite a number of the questions I was going to ask have been answered, but I am still not clear about this £10-20 million that you are talking about with the BBC. Presumably, this will be extra money over and above what they are getting at the moment that you are negotiating with them?

Mr Simon: This is not money that we anticipate giving to them. It is a cost which we anticipate will accrue to them when they are building out new transmitters in order to meet their obligation in respect of universality.

Baroness Howe of Idlicote: So there will be a difference in that they are prepared to go up to 90, but not beyond that?

Mr Simon: The commercial sector will build out to 90 per cent and for the rural areas, the seven or eight per cent beyond that which the commercial sector would not build to because it would not be commercially viable, the assumption is that the BBC will build out that step further and that that will cost them about £10-20 million a year during the period of switchover, which they will later recoup as they make savings from not transmitting anymore on analogue.

Chairman: So you are cutting the budget of the BBC by £10-20 million in that period?

Mr Simon: Well, I do not have any control over the budget of the BBC.

Chairman: You are telling them what to do!

Mr Simon: I am not telling them. I am just telling you what the assumptions are about where the likely build-out will come from.

Baroness Howe of Idlicote: I also want to go back to this whole business of just when the radio switchover is actually going to happen as there are huge question marks over this. I know the target is 2015, but, as you probably also heard, a lot of people do not even want it to happen. If we are looking at FM and the extension of time that may well be required, is the Government prepared to give a guarantee that FM will remain right the way through whatever period it is, even if it takes another ten years or even longer for the total switchover to take place?

Mr Simon: I think the Government can guarantee that FM will remain for the foreseeable future. The Government cannot give guarantees indefinitely, but for the foreseeable future the part of the FM spectrum which will be used for local commercial and community radio will continue to be available for that.

Baroness Howe of Idlicote: Well, could you please define for me the ‘foreseeable future’? How far beyond 2015 would that be?

Mr Simon: I cannot put a number on it, but I would have said it would be well beyond 2015, well beyond.

Baroness Howe of Idlicote: Well, 2020, say?

Mr Simon: My personal guess, for what it is worth, is probably well beyond that.

Baroness Howe of Idlicote: You are probably aware that there will be, and there are already, efforts to get on the face of the Bill a guarantee that it will stay for as long as that.

Mr Simon: A point I would make is that, as far as we are aware, we cannot find any evidence anywhere that the FM spectrum will be, going forward, of any particular economic value to anybody. We are not aware of anybody being likely to want it and certainly to want to pay anything in order to use it for anything else. As long as it remains viable for people to use it for radio, as long as people want to continue to use it for radio and as long as the infrastructure still works, then there is no reason at all why it should not continue. It could be another 50 years.

Baroness Howe of Idlicote: But you did in fact say that it was an ageing infrastructure. Have you got any guess about how long it would remain a viable infrastructure to be used?

Mr Simon: I honestly do not know. There is no sense whatsoever in which I am prevaricating or equivocating, there is nothing that I am trying not to say, but I simply cannot give you any certainty because there is no certainty.

Baroness Howe of Idlicote: I wonder whether Mr Smith might have an answer.

Mr Smith: I have nothing really to add to what the Minister has said. Again, and it is a personal view, but I would expect FM to be available well into the future and I think I would share the Minister’s view of beyond 2020, but we do not know precisely when. The infrastructure is an ageing infrastructure, but who knows how long it might last.

Lord Inglewood: I would just like briefly to turn back to the question of extending the DAB national network because it has been measured in the discussions so far by reference to the percentage of the population, but, since the population is scattered relatively randomly across the country, of the final ten per cent of the population, how much in terms of the total number of transmitters and transmission stations does that represent? In fact, in terms of the total cost of rolling this out, that last ten per cent is going to cost a great deal more than the first ten per cent, is it not?

Mr Simon: In answer to the first question, nobody knows how many transmitters —-

Lord Inglewood: No, but just an order of magnitude; I am not interested in specifics.

Mr Simon: I do not know.

Lord Inglewood: But it is much more than ten per cent of the total cost of the thing, is it not?

Mr Simon: Certainly, you would expect for the non-commercially viable, rural final percentage that the unit cost would be higher than doing the middle of big cities obviously, yes.

Baroness McIntosh of Hudnall: Just on the question of who is listening, there appears to be some evidence, including from Ofcom’s research, that most people who listen to the radio at the moment are pretty happy with what they have got now and that actually this notion of extensive choice and interactivity, which is the key selling point really of digital radio, as you said yourself at the beginning of your evidence, actually does not weigh that heavily with most consumers. We also have heard evidence from John Myers, who was commissioned by the DCMS to report on this, that there is a considerable oversupply of radio services in the sense that there are too many stations out there fulfilling need which is perhaps not as great as they need it to be to be commercially viable, so are you convinced that there really is the consumer-led demand for a digital switchover, or is this really being driven by the fact that the technology exists and, because we can do it, we will do it?

Mr Simon: In the first instance, I think the clearest evidence that there is a demand for digital radio is that in the last ten years ten million digital radio receivers have been bought, and many of them in the earlier years quite expensively and many of them repeat purchases. For a new technology from a standing start where the existing technology remains in place and is dominant, I think that is clear evidence of significant demand and it is a market that continues to grow.

Baroness McIntosh of Hudnall: Before you go on from that, could you just tell us what the percentage of the absolute number of radio sets is, as far as it can be estimated, in the country?

Mr Simon: It is impossible to say because there are wildly different estimations of how many radio sets —-

Baroness McIntosh of Hudnall: Well, on what do you place reliance?

Mr Simon: The estimations of the number of analogue sets in existence, which I can think of having heard, varies between about 40 million and 100 million plus, and it is a technology that is 100 years old, so that is a massive accumulation of equipment and it is, therefore, very difficult to compare with a ten-year-old technology. Out of maybe 50 million meaningful analogue sets, if there have been ten million digital sets sold in the last ten years, I think that shows significant consumer demand for a new technology. On the second question about whether the market is oversupplied, firstly and fundamentally, the size of the market is a matter for the market and for the consumer and it is not ultimately my job to manage the size of the market. However, one thing that we are trying to do with this move, as I have said, is to stratify the market into large national, large regional and very local services, which should mean that, rather than everybody in their rather disorderly fashion competing perhaps on unequal terms in one chaotic market, people can do business more efficiently in a more discrete market, and local commercial radio stations, for instance, can do local commercial advertising that will not overlap and be in competition with big national chains and so on.

Baroness McIntosh of Hudnall: So, leaving aside just the generality of choice as a benefit in itself, if you had to say what the benefits are to consumers of the particular way in which the Government is driving the digital switchover in radio, what would you put as your two or three most significant benefits? Would it be, for example, an extension of nationally available commercial broadcasters on digital platforms, or what would it be?

Mr Simon: I think it would be, firstly, that the technology offers additional benefits, so it offers for most people more stations more clearly defined and a better mix of the different tiers, additional functionality, interactivity; digital radios do things that analogue radios do not. Secondly, I think it offers the consumer an orderly, consistent and coherent pathway to a digital future which is inevitable. The FM technology is ageing and the economics suggest that it would not be economic for major broadcasters to replace that infrastructure nationally and, rather than let it disintegrate in a piecemeal way and let it be replaced in a piecemeal way and have consumers all over the country who no longer can get the services that they have been used to, I think it is appropriate for the Government to try and manage this transition in a coherent way.

Chairman: What I do not quite understand is that you talk about new services being provided, but they are going to be provided in an industry, or you are relying on them being provided in an industry, a particularly commercial industry, which is going to be competing with the BBC, which obviously one wants to see, but that commercial industry itself is struggling, not to survive, but certainly struggling in very, very difficult economic circumstances at the moment. I do not quite see where this expansion is going to come from.

Mr Simon: I am not saying that the aim of the policy is to expand the market for commercial radio. The aim of the policy is to manage the transition in a way that works both for the businesses of the broadcasters and for the consumers and to manage the experience in a way that works for the consumer. As you say, the commercial radio market in terms of revenue has shrunk by a third over the last ten years as advertising revenues have shrunk for all broadcasters, print media and so on. It is a business in which people are under real pressure and that is why, among the overwhelming majority of commercial broadcasters, there is a strong support and an appetite for a clear, managed, relatively swift, but not rushed, pathway to digital where, although in the first instance they will have some additional cost, they can see a future in which they can do more business and make more money.

Lord Inglewood: Just really arising out of that and something you said earlier, it is not part of your case, is it, that, if the analogue network were not ageing and hence degrading, that would not be the reason for moving to digital? The reason for moving to digital is not because the analogue network is simply breaking down, is it?

Mr Simon: The fact that the FM infrastructure will need to be replaced in the short to medium term and that it looks like that replacement would not be economic is certainly one of the underpinning factors.

Lord Inglewood: But that goes back to the question of Lady Howe’s, does it not, that the foreseeable future is actually defined by the capability of the FM infrastructure to deliver the services it currently does?

Mr Simon: I am not sure I understand the question. I understood her question.

Lord Inglewood: Yes, but she said, “How long is it going to go on for?” and you said, “For the foreseeable future”, which was fair, but I think in fact that the way it is defined is that it will go on, according to the evidence you have subsequently given us, for as long as the FM transmission infrastructure is capable of delivering it. When it collapses, that is —-

Mr Simon: They are two different points though. There is the question of how long it will be possible for some people locally to continue to broadcast on FM, which is a different question from at what point do businesses need certainty about the capital investment decisions they might need to take in the future to renew the major national infrastructures.

Lord Inglewood: Sorry, but I may have misunderstood your evidence, in which case I apologise, but I thought what you said was that you did not believe that the industry was prepared to invest for the further life that the FM infrastructure would require.

Mr Simon: That is correct.

Lord Inglewood: If that is the case, why are they prepared to invest in the infrastructure for digital, which is part of the proposal that you are describing to us?

Mr Simon: Because renewing an old technology with its limited functionality does not make economic sense to them, whereas investing in a new technology with additional functionality does. When it comes to making the investment decisions, they are not going to buy the old kit again, they are going to buy the new kit.

Lord Inglewood: I understand the argument, thank you. The other thing I wanted to ask you about was right at the outset when there was a bit of verbal sparring going on between yourself and our Chairman, reference was made to things, such as cheap sets and set-top boxtype devices that would enable analogue radios to pick up digital and so on, and you used the subjunctive, that they might well become available, it was very likely. Is there any assurance that you have been given by any of the manufacturers about the actual provision of these products and, if there is not, as events move on, if it becomes apparent that a lot of this hardware may not be available, will that delay and/or postpone any digital switchover?

Mr Simon: Their adaptor-type technologies are already available for cars, so you can already buy a little thing in Halfords that you can put on your analogue car radio that will enable it to receive the digital signal. I do not think that you can easily get hold of such a product to adapt a domestic transistor radio, but the technology already exists. I am led to believe that they would not be difficult to manufacture and there is no reason to believe that they would be. We are talking to manufacturers who say that such products are on the way.

Lord Inglewood: Do you know in what sort of price range these things might be?

Mr Simon: I honestly do not off the top of my head.

Lord Maxton: On Amazon, £65.

Mr Simon: Currently?

Lord Maxton: For the car one, and you have to buy an aerial as well.

Mr Simon: We expect all of these prices to come down a lot.

Chairman: They have already come down quite a bit, have they not?

Mr Simon: Yes, they have come down tremendously. Digital radios themselves, the cheaper sets, you can now get a set for less than £25, which is very, very greatly less than the cheapest even a couple of years ago. As the market expands, the costs will come down, and it is expanding all over Europe. We are also working with, and encouraging, manufacturers to use, without being too technical, what is called the ‘World DMB Profile One chip’, which is compatible all across Europe, and that will give them great European economies of scale which again should make it easier for them to produce even cheaper sets and adaptors. In answer to the question, if nobody produces these things at affordable cost, would that delay switchover, I think it would depend what effect that had on the market. If that meant that nobody bought them and nobody bought any digital radios either and we did not get over the listenership threshold, then yes, it would delay. If it simply meant that people did not bother with an adaptor, but bought new digital radios, then it would not.

Lord Inglewood: I sense you sense that this is not actually going to be a problem.

Mr Simon: That is my belief.

Baroness Eccles of Moulton: I think, Minister, it is quite clear to us that there is going to be plenty of equipment around for converting, multi-chip, et cetera, et cetera, but why are we continuing to base the whole of our digital radio switchover on what is becoming an outdated system, which is DAB, as opposed to what other countries have done, which is either to scrap DAB or start off with DAB+? Why have we allowed ourselves to get caught in being committed in an early stage of the development of the switchover to what is now not the most up-to-date and modern form of broadcasting?

Mr Simon: That is a very good question which lots of people ask. The answer is that we were in this country by far the earliest adopters as a market of digital radio and we took it up far more quickly and far earlier than anybody else, as a result of which the amount of stock in the market that you would have to write off in this country is vastly greater than European comparators. There are ten million DAB sets, many of which have been bought at early adopter prices in the market in the UK and, if we abandoned DAB, it would mean that all those early digital adopters had their digital investment written off after a very few years, which just seems really counterintuitive in terms of how to drive the market towards digital and hardly also would seem likely to inspire much confidence in those people to make them very likely to buy another digital radio of the new standard. What we are saying is that the new sets henceforth should have the DMB World Profile One chip in, which is DAB, DAB+ and DMB compatible, and it would mean that you could use it anywhere in Europe and receive all that mix of signals. It does not preclude us in the future from moving to a technology which is greater than DAB, but it is a cost-benefit decision that has had to be taken and the clear consensus, not just in the Government, but of the regulators and stakeholders, has been that writing off the ten million DAB sets that have already been bought would be counterproductive.

Baroness Eccles of Moulton: Is including the new chip in any radio that comes on to the market from hereon going to be mandatory in the same way as fitting seatbelts in cars became mandatory?

Mr Simon: Not in the same way in the sense that, I think, seatbelts in cars was a piece of primary legislation, but mandatory in the sense that we will work with manufacturers in order to draw up the technical specifications for the new generations of sets, and they will be the formal technical specifications which will be adopted, hopefully, European-wide, so in that sense mandatory.

Baroness Eccles of Moulton: So you would not be able to sell the set if it did not meet the technical specifications?

Mr Simon: You would not be able to sell an approved set. It would not be a crime to sell a set, but it would look like a dodgy set.

Lord Maxton: France is setting the law which says that by 2012, I think, all radios sold must be DAB+ and that would include all car radios, which is the market area which we really have not looked at, but it is a very important area. Is it right that 20 per cent of all radio listening is in cars? That is a very large percentage, but it is a very difficult area to switch from FM to digital, even with the device which we have talked about already, is it not?

Mr Simon: Our targets are switchover by 2015 and new cars all being digitally radio-ed by the end of 2013. That is our clear target. Now, obviously, even if all new cars are digital by 2013, that still leaves the majority of the car stock analogue for a while beyond 2015, at which point one hopes that the price of the adapters, which you can already buy in Halfords, has come down considerably from the price that you mentioned on Amazon. I did not think they were that expensive in Halfords.

Lord Maxton: Well, they are £79 in the shop and, to be honest, with the reviews they have had of them, you have to almost buy an external aerial.

Chairman: I would not take him on on this!

Mr Simon: I am not going to, not for a minute am I going to! He is obviously speaking with some authority.

Lord Maxton: It will cost you another £12 or £13 on top.

Mr Simon: All I can say is that manufacturers assure us that this technology will be getting cheaper, better and more widely available over the three years before cars go all digital and over the five years until digital switchover. That is a long time for them to make big improvements.

Lord Maxton: I have not got one yet, by the way!

Mr Simon: I guessed!

Chairman: But you said that the target date is 2015?

Mr Simon: Yes.

Chairman: That remains the target date, does it?

Mr Simon: That is the firm target.

Chairman: That is a firm target date and, therefore, will that go into the Bill as a date, the Digital Economy Bill going through at the moment?

Mr Simon: Is it not on the face of the Bill?

Mr Smith: The Bill sets out the conditions which would have to be met for the target to be set.

Chairman: But I think I am right, am I not, that 2015 is not there as a target?

Mr Smith: It is not on the face of the Bill, you are absolutely right.

Chairman: Why not?

Mr Simon: Because it is a target.

Chairman: An aspiration?

Mr Simon: No, I am happy with the word “target”. It is a firm target, but it is not an inflexible or dogmatic target. It relies on our having met the listenership test, met the coverage test and, if we do not meet those tests, then we will not hit that date. We believe that we can, and should, hit that date.

Lord Inglewood: It will not be brought forward?

Mr Simon: That is very optimistic.

Lord Inglewood: I am just asking, not suggesting.

Mr Simon: I think it is unlikely.

Chairman: So you may miss the target. That is basically what you are saying.

Mr Simon: I am saying that, if we do not satisfy the criteria, then we will not do it if the nation is not ready.

[this is an uncorrected and unpublished transcript]