On 8 April 2010 at 1732, the Digital Economy Act was given Royal Assent by Parliament. Who exactly will benefit from the radio clauses in the Act? Certainly not the consumer.

“The passing of the Digital Economy Bill into law is great news for receiver manufacturers,” said Frontier Silicon CEO Anthony Sethill. As explained by Electronics Weekly: “Much of the world DAB industry revolves around decoder chips and modules from UK companies, in particular Frontier Silicon. These firms can expect a bonanza as consumers replace FM radios with DAB receivers.” Frontier Silicon says it supplies semi-conductors and modules for 70% of the global DAB receiver market.

Sadly, the Bill/Act was not really about digital radio at all. For the radio sector lobbyists, it was all about securing an automatic licence extension for Global Radio’s Classic FM, the most profitable station in commercial radio, so as to avoid its valuable FM slot being auctioned to allcomers. The payback on this valuable asset alone easily justified spending £100,000’s on parliamentary smooching. It was interesting to see one Labour MP acknowledge the true purpose for all this parliamentary lobbying in the House of Commons debate when he congratulated “[Classic FM managing director] Darren Henley for making a cause of the issue.”

The clauses in the Digital Economy Bill on the planned expansion of DAB radio and digital radio switchover were simply promises that Lord Carter had insisted upon as the radio industry’s quid pro quo for government assistance to Global Radio’s most profitable asset. The existence of this ‘deal’ between Lord Carter and Global Radio was confirmed by Digital Radio Working Group chairman Barry Cox in his evidence to the House of Lords:

“Lord Carter did not like to do [the deal] immediately. As I understand, he wanted to get something more back from the radio industry. I think there is a deal in place on renewing these licences, yes.”

However, the quid pro quo promise to develop DAB radio will never come to fruition. Now that Global Radio has got what it wanted, over the coming months, the radio industry’s commitment to continue with DAB will inevitably be rolled back. Every excuse under the sun will be wheeled out – the economy, the expense, the lack of industry profitability (having spent nearly £1bn on DAB to date), consumer resistance, the regulator, the Licence Fee, the government (old and new), the car industry, the French, the mobile phone manufacturers, whatever …….

The reasons that digital radio migration/switchover will never happen are no different now than they were before the Digital Economy Bill was passed into law. For the consumer, who seems increasingly unconvinced about the merits of DAB radio, this legislation changes nothing at all. Those reasons, as itemised in my written submission to the House of Lords in January 2010, are:

• The characteristics of radio make the logistics of switchover a very different proposition to the television medium

• The robustness of the existing analogue FM radio broadcasting system

• Shortcomings of the digital broadcast system, ‘Digital Audio Broadcasting’ [DAB], that is intended to replace analogue radio broadcasting in the UK.

More specifically:

1. Existing FM radio coverage is robust with close to universal coverage

• 50 years’ development and investment has resulted in FM providing robust radio coverage to 98.5% of the UK population

2. No alternative usage is proposed for FM or AM radio spectrum

• Ofcom has proposed no alternate purpose for vacated spectrum

• There is no proposed spectrum auction to benefit the Treasury

3. FM/AM radio already provides substantial consumer choice

• Unlike analogue television, consumers are already offered a wide choice of content on analogue radio

• 14 analogue radio stations are available to the average UK consumer (29 stations in London), according to Ofcom research

4. FM is a cheaper transmission system for small, local radio stations

• FM is a cheaper, more efficient broadcast technology for small, local radio stations than DAB

• A single FM transmitter can serve a coverage area of 10 to 30 miles radius

5. Consumers are very satisfied with their existing choice of radio

• 91% of UK consumers are satisfied with the choice of radio stations in their area, according to Ofcom research

• 69% of UK consumers only listen to one or two different radio stations in an average week, according to Ofcom research

6. Sales of radio receivers are in overall decline in the UK

• Consumer sales of traditional radio receivers are in long-term decline in the UK, according to GfK research

• Consumers are increasingly purchasing integrated media devices (mp3 players, mobile phones, SatNav) that include radio reception

7. ‘FM’ is the global standard for radio in mobile devices

• FM radio is the standard broadcast receiver in the global mobile phone market

• Not one mobile phone is on sale in the UK that incorporates DAB radio

8. The large volume of analogue radio receivers in UK households will not be quickly replaced

• Most households have one analogue television to replace, whereas the average household has more than 5 analogue radios

• The natural replacement cycle for a radio receiver is more than ten years

9. Lack of consumer awareness of DAB radio

• Ofcom said the results of its market research “highlights the continued lack of awareness among consumers of ways of accessing digital radio”

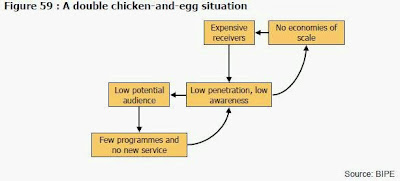

10. Low consumer interest in purchasing DAB radio receivers

• Only 16% of consumers intend to purchase a DAB radio in the next 12 months, according to Ofcom research

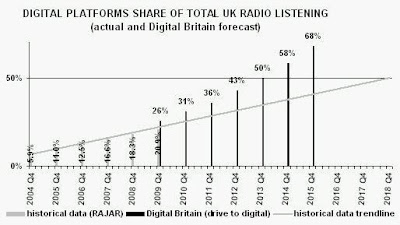

• 78% of radio receivers purchased by consumers in the UK (8m units per annum) are analogue (FM/AM) and do not include DAB, according to GfK data

11. Sales volumes of DAB radio receivers are in decline

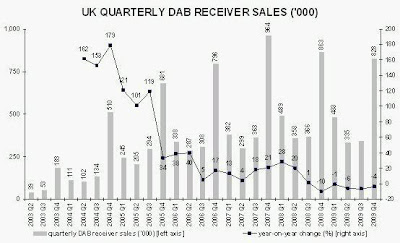

• UK sales volumes of DAB radios have declined year-on-year in three consecutive quarters in 2008/9, according to GfK data

12. DAB radio offers poorer quality reception than FM radio

• The DAB transmission network was optimised to be received in-car, rather than in-buildings

• Consumer DAB reception remains poor in urban areas, in offices, in houses and in basements, compared to FM

13. No common geographical coverage delivered by DAB multiplexes

• Consumers may receive only some DAB radio stations, because geographical coverage varies by multiplex owner

14. Increased content choice for consumers is largely illusory

• The majority of content available on DAB radio duplicates stations already available on analogue radio

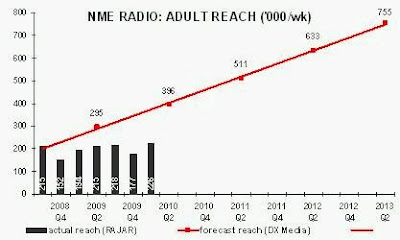

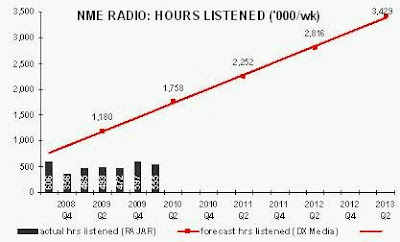

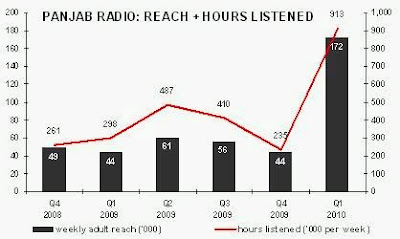

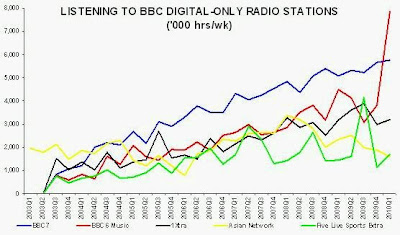

15. Digital radio content is not proving attractive to consumers

• Only 5% of commercial radio listening is to digital-only radio stations, according to RAJAR research

• 74% of commercial radio listening on digital platforms is to existing analogue radio stations, according to RAJAR research

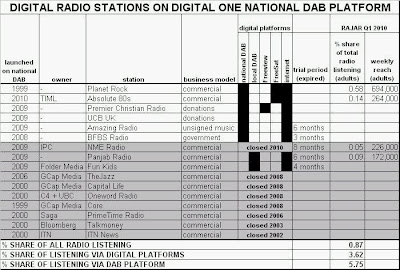

16. Consumer choice of exclusive digital radio content is shrinking

• The majority of national commercial digital radio stations have closed due to lack of listening and low revenues

• After ten years of DAB in the UK, no digital radio station yet generates an operating profit

17. Minimal DAB radio listening out-of-home

• Most DAB radio listening is in-home, and DAB is not impacting the 37% of radio listening out-of-home

• Less than 1% of cars have DAB radios fitted, according to DRWG data

18. DAB radio has limited appeal to young people

• Only 18% of DAB radio receiver owners are under the age of 35, according to DRDB data

• DAB take-up in the youth market is essential to foster usage and loyalty

19. DAB multiplex roll-out timetable has been delayed

• New DAB local multiplexes licensed by Ofcom between 2007 and 2009 have yet to launch

• DAB launch delays undermine consumer confidence

20. Legacy DAB receivers cannot be upgraded

• Almost none of the 10m DAB radio receivers sold in the UK can be upgraded to the newer DAB+ transmission standard

• Neither can UK receivers be used to receive the digital radio systems implemented in other European countries (notably France)

21. DAB/FM combination radio receivers have become the norm

• 95% of DAB radio receivers on sale in the UK also incorporate FM radio

• 9m FM radios are added annually to the UK consumer stock (plus millions of FM radios in mobile devices), compared to 2m DAB radios, according to GfK data

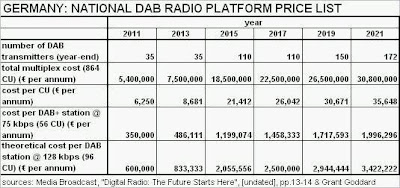

22. DAB carriage costs are too high

• Carriage costs of the DAB platform remain too costly for content owners to offer new, commercially viable radio services, compared to FM

• Unused capacity exits on DAB multiplexes, narrowing consumer choice

23. DAB investment is proving too costly for the radio industry

• The UK radio industry is estimated to have spent more than £700m on DAB transmission costs and content in the last ten years

• The UK commercial radio sector is no longer profitable, partly as a result of having diverted its operating profits to DAB

24. DAB is not a globally implemented standard

• DAB is not the digital radio transmission standard used in the most commercially significant global markets (notably the United States)

These factors make it unlikely that a complete switchover to DAB digital terrestrial transmission will happen for radio in the UK.

With television, there existed consumer dissatisfaction with the limited choice of content available from the four or five available analogue terrestrial channels. This was evidenced by consumer willingness to pay subscriptions for exclusive content delivered by satellite. Consumer choice has been extended greatly by the Freeview digital terrestrial channels, many of which are available free, and the required hardware is low-cost.

Ofcom research demonstrates that there is little dissatisfaction with the choice of radio content available from analogue terrestrial channels, and there is no evidence of consumer willingness to pay for exclusive radio content. Consequently, the radio industry has proven unable to offer content on DAB of sufficient appeal to persuade consumers to purchase relatively high-cost DAB hardware in anywhere near as substantial numbers as they have purchased Freeview digital television boxes.

Additionally, it has taken far too long to bring DAB radio to the consumer market, and its window of opportunity for mass take-up has probably passed. Technological development of DAB was started in 1981, but the system was not demonstrated publicly in the UK until 1993 and not implemented for the consumer market until 1999. In the meantime, the internet has expanded to offer UK consumers a much wider choice of radio content than is available from DAB.

In this sense, DAB radio can be viewed as an ‘interim’ technology (similar to the VHS videocassette) offering consumers a bridge between a low-tech past and a relatively high-tech future. If DAB radio had been rolled out in the early 1990s, it might have gained sufficient momentum by now to replace FM radio in the UK. However, in the consumer’s eyes, the appeal of DAB now represents a very marginal ‘upgrade’ to FM radio. Whereas, the wealth of radio content that is now available online is proving far more exciting.

The strategic mistake of the UK radio industry in deciding to invest heavily in DAB radio was its inherent belief in the mantra ‘build it and they will come.’ Because the radio industry has habitually offered content delivered to the consumer ‘free’ at the point of consumption, it failed to understand that, to motivate consumers sufficiently to purchase relatively expensive DAB radio hardware would necessitate a high-profile, integrated marketing campaign. Worse, the commercial radio sector believed that compelling digital content could be added ‘later’ to DAB radio, once sufficient listeners had bought the hardware, rather than content being the cornerstone of the sector’s digital offerings from the outset.

In my opinion, the likely outcome is that FM radio (supplemented in the UK by AM and Long Wave) will continue to be the dominant radio broadcast technology. For those consumers who seek more specialised content or time-shifted programmes, the internet will offer them what they require, delivered to a growing range of listening opportunities integrated into all sorts of communication devices. In this way, the future will continue to be FM radio for everyday consumer purposes, with personal consumer choice extended significantly by the internet.