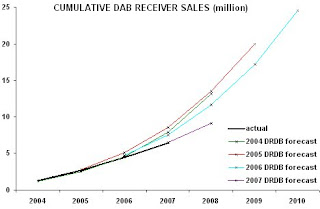

The Digital Radio Development Bureau, the trade body charged with promoting the DAB platform, issued a press release today stating that the “one ray of sunshine in a gloomy Christmas season for retailers was DAB digital radio”. Its statement failed to mention the negative growth experienced in what is traditionally the most critical quarter of the year for DAB radio sales. Retail data collected by GfK for the DRDB clearly show the declining growth rate of DAB radio sales having started in the second quarter of 2008, a trend that is likely to have been further exacerbated by the ‘credit crunch’.

The Digital Radio Development Bureau, the trade body charged with promoting the DAB platform, issued a press release today stating that the “one ray of sunshine in a gloomy Christmas season for retailers was DAB digital radio”. Its statement failed to mention the negative growth experienced in what is traditionally the most critical quarter of the year for DAB radio sales. Retail data collected by GfK for the DRDB clearly show the declining growth rate of DAB radio sales having started in the second quarter of 2008, a trend that is likely to have been further exacerbated by the ‘credit crunch’.

However, this disastrous sales performance has not prevented those UK companies who are pushing the DAB platform from continuing to talk up the success of their technology. Imagination Technologies, the parent company of the Pure Digital brand of DAB radio receivers, today

announced “record export growth for 2008” and that it “had more than tripled overseas sales in the year ending 31 December 2008”. Hossein Yassaie, Chief Executive of Imagination Technologies, said: “Our strong overseas growth is further evidence that DAB digital radio is gaining traction worldwide, and that the transition to digital radio is inevitable.”However, overseas markets

account for only 15% of Pure Digital sales (half-year to end October 2008), so why did Imagination Technologies feel it worthwhile to issue a press release for a relatively insignificant revenue stream? It is probably because Imagination has to convince Lord Carter that the government should back DAB radio technology as part of his recommendations within the forthcoming Digital Britain report. Imagination Technologies has bet the farm on DAB becoming a successful, global technology. If the UK government does not decide to force radio listeners to migrate to DAB technology, Imagination could lose its shirt.Imagination Technology’s interim results, published six weeks ago,

admitted that revenues from its Pure Digital DAB radio receivers were up only 2% year-on-year, a result it attributed to “the downturn” in the UK market, which still accounts for 85% of its global sales. Chief Executive Hossein Yassaie said there had been a “UK slow-down” of DAB radio receiver sales and noted that “the introduction of lower price radios and the onset of the recession meant that the increase of the UK DAB market was less than 5%”. Pure Digital Marketing Director Colin Crawford said this week: “Our [DAB] sales at Christmas were good, though a little bit down on last year.”Disappointing sales figures seem only to have encouraged the DAB protagonists to push the boundaries of their government lobbying beyond the limits of truthfulness. In its latest annual report, Imagination Technologies

claimed that “DAB has reinvigorated the now rapidly growing UK radio market and effectively replaced analogue radio”. The latter statement is untrue. According to industry data, only 21% of radio receivers sold in the UK during the last twelve months were DAB, the remaining 79% being old fashioned analogue. The overwhelming majority of radios in use in the UK remain analogue, and DAB is nowhere near having “effectively replaced” them. Another corporate victim of over-enthusiastic government lobbying for DAB is Frontier Silicon, whose Chief Executive Anthony Sethill was quoted in a company press release issued in December 2008 as saying: “Digital radio is here to stay, with DAB sets outselling analogue models by six to one”. Once again, the industry data demonstrates this statement to be a blatant untruth, and simply part of a desperate campaign by a clutch of inter-connected companies to convince the government that DAB technology is already a ‘success’ in the UK.

Another corporate victim of over-enthusiastic government lobbying for DAB is Frontier Silicon, whose Chief Executive Anthony Sethill was quoted in a company press release issued in December 2008 as saying: “Digital radio is here to stay, with DAB sets outselling analogue models by six to one”. Once again, the industry data demonstrates this statement to be a blatant untruth, and simply part of a desperate campaign by a clutch of inter-connected companies to convince the government that DAB technology is already a ‘success’ in the UK.

Frontier Silicon is a privately owned UK company which

describes itself as “the world’s leading supplier of innovative semiconductor, module and software solutions for digital radio and connected audio systems”. Its electronic modules are in 80% of all DAB radios, making it “the number one supplier to the DAB/DAB+ market”. In 2003, Imagination Technologies took a 17% equity stake and £1.25m of loan stock in Frontier Silicon. Imagination has an 80% share of the worldwide market for the intellectual property on DAB chips, which are then incorporated into Frontier Silicon’s modules. However, in 2008, Imagination’s stake in Frontier Silicon had to be written down from £7 million to £3.6 million, likely a result of slowing DAB take-up.Another of Frontier Silicon’s ten investors is Digital One, the owner of the UK’s only national commercial radio DAB multiplex. Digital One is controlled by Global Radio, the UK’s largest commercial radio group, owner of one national station, dozens of local stations and with stakes in the majority of local DAB multiplexes. For Imagination Technologies, Frontier Silicon, Digital One and Global Radio, a decision by the UK government to implement a forced consumer migration to DAB radio would have a hugely beneficial impact on their financial performances. For Imagination, which reported its first profitable year in 2007/8 (£1.88 million pre-tax profits), it might even turn the company’s forecast 2010/11 pre-tax profit of £11.84 million into a reality.

More than a decade ago, the idea of a few bright sparks in the government’s Department of Trade & Industry was that DAB radio technology could be quickly made a hit in the home market, take-up would then spread globally, and DAB would become a hugely profitable technological export for the UK. This dream continues to be espoused by Intellect, the trade association of the UK technology industry, which

told Lord Carter in December 2008:“The UK is the home of the major chip manufacturer of DAB silicon, as well as two leading receiver manufacturers and, as such, is uniquely positioned to benefit from the potential expansion of DAB not just in the UK, but globally. We believe that this example of high value manufacturing could make a substantial contribution to the UK’s future prosperity………….”

Unfortunately, the dream is not working out as planned. DAB take-up in the UK market has proven laboriously slow and is in danger of being superseded by newer technologies. Worse, overseas markets have shown little interest in DAB. In Europe, only Denmark has a DAB market as developed as the UK’s. Globally, Australia is about to launch DAB but the largest market, the US, has chosen a different digital radio standard. Several countries have experimented with DAB and since abandoned the technology.

With overseas markets looking less likely to prove a source of significant export revenues, the UK technology companies pushing DAB have become increasingly desperate to ensure that their products at least succeed in their home market. Hence, their desperation to persuade the government to force a consumer switchover from FM to DAB. The average household owns six radios, and a government-backed FM switch-off will force all six to be replaced with shiny, new DAB radios. That’s a lot of potential revenue for a select number of UK technology companies.

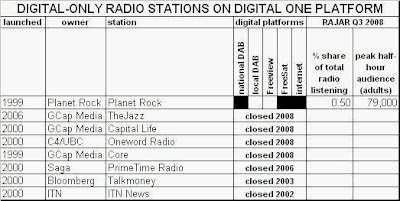

It hardly inspires confidence in the Digital One DAB platform that Global Radio’s predecessor, GCap Media, closed three of its own digital-only stations carried on its platform last year, and sold Planet Rock to an entrepreneur with no other radio interests. Neither is it a good advertisement for Digital One that its

It hardly inspires confidence in the Digital One DAB platform that Global Radio’s predecessor, GCap Media, closed three of its own digital-only stations carried on its platform last year, and sold Planet Rock to an entrepreneur with no other radio interests. Neither is it a good advertisement for Digital One that its