The Digital Britain Final Report published in June 2009 proposed that the UK radio industry embark on a ‘Digital Radio Upgrade’ which would seem to involve (take a deep breath):

· Providing greater choice and functionality for listeners (para.15)

· Listeners who can currently access radio can still do so after Upgrade (para.15)

· Building a DAB infrastructure which meets the needs of broadcasters, multiplex owners and listeners (para.21)

· Redrawing the regional DAB multiplex map (para.21)

· The BBC beginning “an aggressive rollout” of its national DAB multiplex to ensure its coverage achieves that of existing FM by 2014 (para.23)

· Commercial radio to extend the coverage of its national DAB multiplex and to improve indoor reception (para.21)

· Investment to ensure that local DAB multiplexes compare with existing FM coverage (para.24)

· The extension and improvement of local DAB coverage (para.25)

· Measures to address the existing failings of the existing DAB multiplex framework (para.26)

· The merger of adjoining local DAB multiplexes and the extension of existing multiplexes into currently unserved areas (para.26)

· The existing regional multiplexes to consolidate and extend to form a second national commercial radio multiplex (para.26)

· Convincing listeners that DAB offers significant benefits over analogue radio (para.28)

· DAB to deliver “new niche [radio] services” and to gain better value from existing content (para.29)

· DAB to offer more services other than new stations (para.30)

· DAB to offer greater functionality and interactivity (para.31)

· Implementation of digitally delivered in-car traffic and travel information (para.31)

· DAB radio receivers to be priced at below £20 within two years (para.32)

· Introduction of add-on hardware (similar to Freeview boxes) to enable consumers to upgrade their analogue receivers (para.32)

· Energy consumption of DAB radio receivers to be reduced (para.33)

· New cars to be sold with digital radios by 2013 (p.99 box)

· A common logo to identify and label DAB radios (p.99 box)

· Development of portable digital radio converters (p.99 box)

· Integration of DAB radio into other vehicle devices such as ‘SatNav’ (p.99 box)

· Work with European partners to develop a common approach to digital radio (p.99 box)

A lengthy list. And who is going to pay for all this? Digital Britain stated that “the investment needed to achieve the Digital Radio Upgrade timetable will on the whole be made by the existing radio companies” (para.44). This means the BBC and the commercial radio sector. And what exactly do these radio broadcasters think about having to pay for all these proposals without the aid of specific government funding? A seminar organised by the Westminster Media Forum this morning gave us an opportunity to find out. Here’s what was said about the Digital Radio Upgrade issue (speech excerpts):

Caroline Thomson, Chief Operating Officer, BBC [‘CT’]:

“The [Digital Britain] report is clear that there is an ambitious target for analogue switch-off in 2015. It is an ambitious target. Radio switch-off is a very different issue from television switchover, but we are supportive of this ambition and we will work with partners in the industry towards delivering it. And we have already made a lot of progress working with commercial radio to develop the policies on this. But, at the heart of it, we must remember that we must put listeners first and be careful not to damage the ability of listeners to tune in to the content they love. Working with commercial radio to secure the digital future in a way that will work for all our listeners is a crucial part of this. As my colleague Tim Davie, Director of [BBC] Audio & Music, said recently: ‘unless we huddle together for scale, we are going to be in trouble’. The BBC is drawing up our digital rollout plans in radio to see where and when it is possible to extend DAB coverage, and how much it would cost. We are willing partners, and DAB is a good example of an area of the Digital Britain report where we are helping to meet the charge.”

Andrew Harrison, Chief Executive, RadioCentre [‘AH’]:

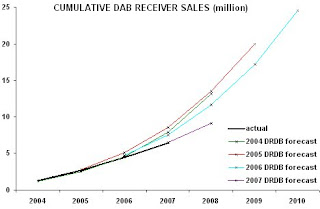

“The real choice, which Digital Britain identifies, is which broadcast platform do we want – FM or DAB. And here, the genie is out of the bottle. DAB now exists on 10m sets, the BBC will not withdraw 6Music and BBC7 or the Asian Network or Five Live Extra – it never withdraws services – and commercial services will not fold DAB-only stations like Planet Rock or Jazz FM. Digital Britain has been clear in its aspiration – national, regional and larger local stations will have a clear pathway to upgrade to DAB and switch off FM. Smaller players will have a clear opportunity to remain on FM without an obligation to move across to DAB. Strategically, that’s a simple resolution – both will co-exist. So, next we need a plan to work out how we might achieve the migration criteria – on transmitter coverage, set sales and in-car penetration. The devil inevitably will be in the detail. But we need two strong interventions from government – on coverage and on cars – before any migration plan will be taken seriously. On cars, Digital Britain falls short of mandating manufacturers, unlike in France, to put digital radio in all cars from 2013. Encouragingly, Ford and Vauxhall have both confirmed their intent to upgrade in line with the timeline for 2013, but we need government to force the pace. On coverage, Lord Carter has ducked the funding issue. The commercial sector has already built out its national and local multiplexes as far as is commercially viable. So I’m delighted to hear Caroline emphasise that the BBC is supportive of the direction and ambition for digital radio and are willing partners helping to fund the change. It’s now time for the BBC and government to stop their wider dance around the BBC’s future role and theoretical possible future uses of the Licence Fee which have never been paid for before, and [to] instead consider how to broker a coverage plan for digital radio that will make it happen.”

Carolyn McCall, Chief Executive, Guardian Media Group [‘CM’]:

“It’s hard to escape the feeling that what the Digital Britain report has done is just gone: ‘we recognise the issue, big issue DAB’. They said something like that, which is pretty important, but they have just gone: ‘Ofcom, deal with it’. That’s how it strikes me. It just seems that so much of this on radio is being left to Ofcom to deal with. And if what I read is true, David Cameron doesn’t want an Ofcom anyway. So that is quite a serious issue for us as an industry. The most worrying aspect of the report in relation to radio is the assertion that investment needed to achieve the Digital Radio Upgrade will be made by existing radio companies. Effectively, the promise of deregulation is being made conditional on commercial radio funding digital [upgrade], stumping up more money that the commercial industry simply cannot afford. We’ve always had too much regulation for a small industry struggling in an unregulated digital world. While we back DAB, I don’t think any commercial broadcaster is going to feel comfortable about paying for those developments. The final point on radio is that, at a time when that industry in particular needed some clarity, the report does not give us any clarity. What new powers will Ofcom have, what role will they be expected to play, what is the position on the vital issue of Format change, what is meant by greater flexibility in relation to co-location, and mini-regions? The list goes on. I would say to Stephen [Carter], or Ben [Bradshaw], or indeed Jeremy Hunt, we need urgent clarifications on these issues and quickly.”

Q&A session [excerpts]:

[Is analogue radio switch-off going to include the [BBC] Radio 4 Long Wave signal?]

CT: That is the government policy. The policy is to switch off all analogue radios.

[Existing DAB coverage is not good enough?]

AH: Right now, self-evidently, DAB coverage is not good enough for anyone to consider switchover. There is a bill to be paid to deliver that public policy imperative. As long as that bill is met and covered, I think the BBC and the commercial sector would confidently switch over knowing the coverage is better ….

[Unless you start spending money now, and if you are, where is it going to come from, it’s not going to happen, is it?]

CT: First of all, we will not do the analogue switch-off unless it is the case that there are very big thresholds that have already been passed, particularly about car radios. And the challenges of getting to those thresholds by 2013, which is what we’ve said, are enormous, even if we build out the transmission. So let me just be clear. It is not the BBC’s policy to switch off FM or Long Wave until we are secure and clear – that is why I made the reference to listeners in my speech – that that is the policy which will work for listeners. On the money, for now we don’t have the money to build out beyond 90% – that is our current build-out – and the final 10% costs much more per percentage than the previous 90%, but we will look forward to a discussion with the government about it. We would like to be able to do it because, in the long term, as for commercial radio, running dual illumination [FM/DAB simulcasting] costs a lot of money so a switchover in 2020 costs us more than a switchover in 2015. But we won’t do the switchover in 2015 unless we believe particularly that car radios are up …..

CM: This point about digital radio [switchover]. There are no funds. I am not really convinced […noise…] and margins are slim because everyone has been hit by the recession quite badly. I don’t know where the money is going to come from for digital switchover of radio.

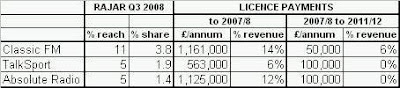

AH: I remain confident that where we are now with Digital Britain from the radio perspective is into the negotiation now – who pays for this? Frankly that is a negotiation that is far more likely to be concluded positively in the next few months between the BBC and a Labour government than under a Conservative government, so I remain optimistic that both sides will be brought to the table. In terms of who pays and who can afford this, the reality is that the BBC Licence Fee is £3.5bn, that’s seven times the total income of commercial radio. The cost of DAB coverage build-out is about £5m a year – that’s less than Jonathon Ross’ salary or Michael Lyons’ pension fund – so it’s purely a question of priorities for the BBC. I would have thought that it is quite within the limit of the BBC’s talented management to come up with a solution that can meet the public purposes set out for DAB and still deliver all the wonderful content that we enjoy.