Digital radio switchover was first mooted in the 1980s and started to gather momentum following the first UK public demonstration of the DAB digital transmission system at the Radio Festival in Birmingham in 1991. New Scientist magazine reported then that DAB radio could be up and running in the UK “by the mid-1990s”. However, it was not until 1999 that DAB radio was launched publicly and DAB radio receivers were made available commercially.

Over this period of decades, it would have been sensible to commission some kind of cost-benefit analysis to assess if there were a potential net benefit to radio listeners, to the radio industry, and to the UK generally of embarking on a plan to convert the whole nation to digital terrestrial radio. If such an analysis was ever published, I must have missed it.

We are now in 2010, an incredible 29 years after research and development first started on DAB radio technology. The issue of digital radio switchover has been the subject of a succession of government initiatives since the end of 2007 (the Digital Radio Working Group, Digital Britain, the Digital Economy Bill). Has the government shared with the public a cost-benefit analysis which demonstrates that the public policy on digital radio pursued over the last 20+ years is somehow worthwhile? No. Does such a cost-benefit analysis exist? Yes. Can we see it? No. Where is it? Apparently, gathering dust on a government or Ofcom shelf.

How do we know this? A parliamentary committee recently delved into these facts during its current investigation into the issues surrounding digital switchover in the television and radio markets (see transcript below). Ofcom has remained remarkably silent on the issue of digital radio switchover in recent years. The regulator’s director of radio, Peter Davies, was last seen speaking publicly about DAB in November 2008 when he admitted that new legislation would be necessary to salvage the DAB platform. A little earlier, in April 2007, Davies had prematurely declared that “we are potentially at a Freeview moment with digital radio.” Three years later, radio’s ‘Freeview moment’ seems as far over the horizon as ever.

The first we knew that the government had commissioned some kind of cost/benefit analysis [CBA] for its proposed digital radio switchover was in November 2009 when the Digital Economy Bill was published. The government’s accompanying Impact Assessment document stated:

“The partial Cost Benefit Analysis conducted by Price Waterhouse Cooper (PWC) for the Digital Radio Working Group, which is available on the DCMS website, suggests the Digital Radio Upgrade could reduce the total transmission costs for the radio industry from £87.9 million to £64 million….”

“First, by supporting greater investment in DAB infrastructure a greater number of consumers will have access to DAB and the quality of reception will improve. Secondly, consumers will benefit from access to a wider range of services, specifically new national stations and functionality, such as pausing and rewinding live radio. Finally, the released analogue spectrum will allow for a greater range of community radio stations, as well as possible non-radio services. The PWC partial CBA for the Digital Radio Working Group suggests the value of these benefits could be in the region of £1.1 billion, over a period from 2009 to 2030…..”

“The significant consumer costs of the Digital Radio Upgrade in the non-voluntary conversion of analogue sets to digital, including the cost of in-car conversion. The PWC report suggested the cost of such conversion to be in the region of £800 million, again over the period from 2009 to 2003.” [typo – “2003” should be “2030”]

Although this document stated that the PWC report was available from the government’s web site, I have searched for three months and still never found it there. Nevertheless, the 91-page report entitled ‘Cost Benefit Analysis of Digital Radio Migration’, prepared for Ofcom by PWC on 6 February 2009, contains a number of very serious reservations that there will be ANY benefit from digital radio switchover, and it states:

“The results suggest that there are relatively few up-sides to the estimates, and several significant downside risks. … To a significant extent, the positive Net Present Value [NPV] of the Cost Benefit Analysis relies on two crucial parameters. The first is the Digital Radio Working Group [DRWG] recommendation that an enlarged regional [DAB] multiplex network should be implemented. Failure to implement would result in a substantial negative NPV. The second critical parameter is the time horizon. The results suggest that there is a very long pay-back from the DRWG policy ‘investment’ – the NPV turns positive after 2026. This result assumes that the existing multiplex licences are extended to 2030, as per the DRWG recommendations. Without the licence extension or any other policy instruments that provide clarity on the long term future of commercial radio, the industry and consumers may fail to see the benefits of digital radio over the longer term. Our analysis suggests that the NPV is negative should either of these two proposals not be implemented.” [emphasis added]

The PWC report explicitly noted for Ofcom the limitations of its analysis, as a result of the lack of consideration it had assigned to external factors. These paragraphs probably explain why the government has been so keen to keep the report away from public scrutiny:

“The scope of this study is limited to the assessment of the DRWG policy. The overall digital radio policy appraisal process would need to take into account other policy options and ‘states of the world’. With this in mind, we highlight three issues in particular:

1. The impact of recession: We have assumed no change in commercial radio sector structure and health beyond a consensus view of advertising forecasts. As this CBA is conducted for the time period to 2030, short term recessionary impacts may have only a limited impact on the longer term outcome for the industry. On the other hand, the current economic downturn could still affect the short and medium term investments required for marketing or coverage extension, which in turn could delay the desired DRWG policy outcome.

2. Other policy options: We recognise that to reach a view on this question of how to drive digital radio penetration and listening (which in turn delivers consumers’ and citizens’ objectives) requires a full assessment of the costs and benefits of a number of policy options; this study has examined one, the DRWG policy. This is the only policy assessed in this study and the policy is at an early stage of its development; Government and Ofcom could give consideration to other possible policy options. In addition, we recommend modelling a number of other ‘business-as-usual’ scenarios taking into account different assumptions, and assessing how they affect the CBA of the DRWG policy.

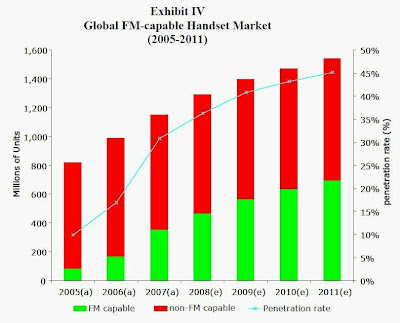

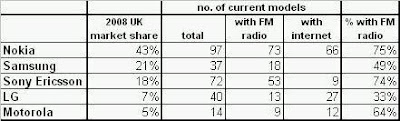

3. Other digital platforms: This CBA assumes that DAB listening will continue to be the leading platform for digital radio listening. The DRWG has reinforced the view that ‘a radio-specific broadcast platform is an essential part of radio’s future’, and that DAB is the ‘most effective and financially viable way of delivering digital radio’ for the medium to long term. A long term view needs to account for the possibility of technology obsolescence or replacement. At present, there is no consensus view that suggests otherwise. However, there are signs that internet listening may begin to take off if internet radios are more actively promoted and technologies such as WiFi or mobile broadband mature and become universally available. A number of the cost and benefit categories assume an impact from increasing the coverage of DAB (for example, consumer benefits from increased coverage is assumed based upon the incremental benefits to consumers who could not receive digital radio stations). Should these trends continue, or a more structural shift to internet to occur, there would be a smaller benefit from increasing the coverage of DAB; consumers either have alternative access to digital radio even within out-of-coverage areas, or would prefer a non-DAB solution when they receive DAB coverage.” [emphasis added]

In the 12 months since the PWC report was prepared, all three of these assumptions have been undermined by subsequent events:

1. The health and structure of the commercial radio industry have changed considerably during 2009:

• Commercial radio’s financial health has been impacted severely by the recession. The sector’s revenues were down 19.5%, 10.8% and 12.5% year-on-year in the first three quarters of 2009. Revenues from national advertisers were down 28.8%, 16.1% and 16.5% respectively

• In January 2009, an analysis commissioned by RadioCentre found that “the [commercial radio] industry as a whole is now loss making”. Hours listened, revenues and profitability have all fallen further since then

• At the beginning of 2009, Global Radio was the biggest owner of DAB multiplex infrastructure. Since then, it has disposed of its entire stake in the national DAB multiplex and most of its stakes in local DAB multiplexes to transmission provider Arqiva, demonstrating the radio sector’s inability to generate profits from the DAB platform after 10 years

2. The policy recommendations for digital radio switchover made by the Digital Radio Working Group have since been amended by the Digital Britain report and the Digital Economy Bill. The recommendations of the Working Group’s Final Report published in December 2008 had included:

• “Government should agree a set of criteria and timetable for migration to digital”, whereas no criteria or timetable are specified in the Bill

• “A long term plan should be developed to move all services to digital”, whereas the Bill acknowledges that some local radio stations will never have the opportunity to migrate to digital

• “The BBC should build out its national [DAB] multiplex across the UK to reach FM comparable levels [of coverage]”, whereas the BBC has acknowledged that such expenditure is constrained by the Licence Fee settlement

• “The government should consider funding options to enable this important investment [in DAB infrastructure]”, whereas the government has made no financial commitment to the build-out of DAB multiplexes

• “The government must consider the case for a [import] duty exemption for digital radios”, a proposal that is not mentioned in the Bill

• “Consumer groups believe that, once an announcement [of digital switchover] is made, no equipment should be sold that does not deliver both DAB and FM”, a proposal that has been dropped

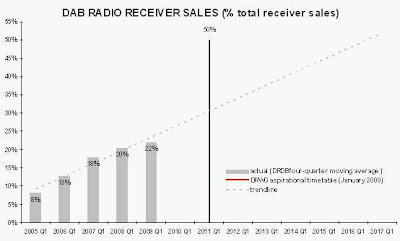

3. The DAB platform has failed to grow in 2009, as had been forecast by the government, Ofcom and the Digital Radio Development Bureau [DRDB]:

• Volume sales of DAB radio receivers were down 10%, down 1% and down 6% year-on-year in the three most recent quarters for which data have been released by the DRDB

• Listening to radio via digital platforms accounted for 20.9% of total radio listening at year-end 2009, compared to the 26% forecast by the government’s Digital Britain report in June 2009 (and compared to the 42% forecast by Ofcom in November 2006)

• Listening to commercial radio via digital platforms accounted for 19.7% of commercial radio listening at year-end 2009, compared to the target 30% announced by RadioCentre in January 2007

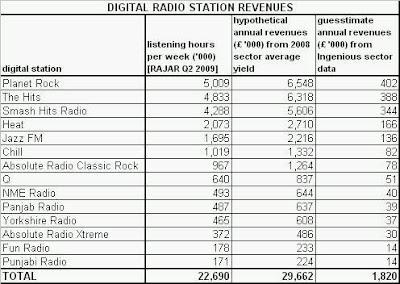

• Total hours listened to digital-only radio stations at year-end 2009 were at their lowest level since 2007, demonstrating that digital radio content is failing to drive consumer take-up of digital radio

• Unused capacity on the DAB platform has increasingly been filled during 2009 by non-commercial, government-funded, listener-funded, religious or ethnic radio services, rather than by mainstream, mass appeal stations

• The commercial radio sector launched no completely new broadcast digital radio stations in 2009 (Absolute Xtreme was replaced by Absolute 80s), and the BBC is expected to announce cuts to its digital radio stations at the end of this month

As a result of these developments during 2009, the minimal, long term benefits from digital radio switchover identified by the PWC report a year ago are likely to have been diminished to the point where there may no longer be any benefit evident at all, even as far into the future as 2030. So how can the government still justify pursuing its policy of digital radio migration? It cannot, which is why it remains so reluctant to engage in an analysis of the facts, the numbers, the data and the evidence, all of which clearly show that this misguided, poorly executed, top-down attempt to switch radio broadcasting in the UK to the DAB platform is likely to become a ‘white elephant’ that has already cost the radio industry getting on for £1 billion.

House of Lords

The Select Committee on Communications

“Digital Switchover Of Television And Radio In The UK”

27 January 2010 [excerpts]

Witnesses:

Mr Stewart Purvis, Partner for Content and Standards, Ofcom

Mr Peter Davies, Director of Radio Policy & Broadcast Licensing, Ofcom

Mr Greg Bensberg, Senior Adviser, Digital Switchover, Ofcom.

Baroness McIntosh of Hudnall: I feel we could get back on to slightly safer territory and the notion of cost and benefit. We understand that you commissioned a report from PWC last year into the costs and benefits of digital switchover in radio, but you didn’t publish it. We know, therefore, what we have learned from the DCMS about what it said. It appears that it found, for example, that the benefits could – and I emphasise the word “could” – outweigh the costs by £437 million after 2026, but that conclusion is hedged about with quite a lot of caveats to do with what would have to happen in order for that good outcome to eventuate, and that if those things didn’t happen, then quite quickly you would get into a position where the costs would outweigh the benefits. Can you tell us a bit about that report? In particular, can you tell us why you haven’t published it? Do you think that, given what it appears to say – I choose my words carefully – about the constraints on potential for benefit, that it should have been available to inform the Government’s digital policy? Can you also tell us about your own impact assessment on radio digital migration, which I believe you have been asked to undertake? Will this include a full cost-benefit analysis? When are you intending to publish it? ….. [edited]

Mr Purvis: There are a lot of questions there. Peter commissioned the piece, so I am going to ask him to talk to them, but let me say that you have talked about informing the Government’s decision and one of the main points of doing this was to help inform the Government’s decision. It was a government decision as to whether this information should be published or not. But, we felt, as part of the ….

Lord Gordon of Strathblane: Sorry, it was your document, though, wasn’t it?

Mr Purvis: No, it was actually a PWC document.

Lord Gordon of Strathblane: It was commissioned by you.

Mr Purvis: Commissioned by us, yes.

Lord Gordon of Strathblane: Surely, it would be your decision to publish.

Mr Davies: We were asked to commission it by the Government. We then commissioned it from PWC with a lot of input from various government departments and then submitted it to the Secretary of State.

Chairman: So you decided not to publish it.

Baroness McIntosh of Hudnall: Who owns it?

Mr Purvis: Whenever you commission a document from an outside source, in a sense the ownership of the detail must lie with the people who actually did the work, but, in a sense, when you commission it, obviously you commission it with a purpose and the purpose was to give it to the Government.

Baroness McIntosh of Hudnall: With respect, that is not necessarily true.

Mr Purvis: No, there are options.

Baroness McIntosh of Hudnall: I have work commissioned from me and it may be, and often is, on the understanding that the ownership of what I produce falls to the person who commissioned it from me.

Mr Purvis: Yes, that’s true, but in terms of the ownership. But in the sense of the responsibility for the detail of the commission, the source of the commission must inevitably take its full share of that. But there are a number of options which apply when these pieces of work are done. On this particular occasion, it was decided in conjunction with the Department that work would be sent to the Department. Perhaps the most important thing is for Peter to respond to your characterisation of the work, but, in a sense, we have not hidden the piece of work. Indeed, I think it is now available to you. Is that right?

Baroness McIntosh of Hudnall: In, as they say, a redacted form.

Chairman: Just to be absolutely clear, the Department asked you to commission the work from PWC. Is that what you are saying?

Mr Purvis: They asked us to commission the work. Did they ask us specifically from PWC?

Mr Davies: Not specifically from PWC.

Chairman: The Department said to Ofcom, “Ofcom, you go and commission this particular work.” Is that the position?

Mr Davies: Yes.

Chairman: You then got the work which then came back to you and then you sent it to the Government and the Government said, “We’re not going to publish this in full.”

Mr Davies: I think they have certainly made it available to various groups. I think consumer groups have had it for some time.

Chairman: Fine. There will be no problem, therefore, in this Committee having the full report.

Mr Davies: I think they have made available the redacted version rather than the full report. The reason for that is some of the numbers in there are commercially sensitive, but there is no reason why the Committee should not have the full report.

Mr Purvis: You certainly have seen the conclusions.

Baroness Howe of Idlicote: I just wonder who has paid for it. Has it come out of your budget?

Mr Davies: Yes.

Baroness Howe of Idlicote: Even more indication of ownership.

Baroness McIntosh of Hudnall: Shall we go back to the questions. We now know why you didn’t publish it. Am I right in thinking that, notwithstanding the fact that you did not publish it, it did influence the Government or is in the process of influencing the Government as far as their policy on digital migration goes?

Mr Davies: I think it is one of the inputs to government thinking, certainly. We were very careful when we sent it to the Secretary of State to make clear what all the caveats were. You are absolutely right, there are a lot of caveats around it. This is a piece of work which is at a very early stage of the process. We were very clear to government that they should not use this as the means of making a decision, but it might help to inform the decision.

Baroness McIntosh of Hudnall: The thing that is slightly troubling – perhaps only to me, but a bit – is that when you see what appears to be evidence that the costs and benefits are, let’s say, finely balanced, or could be, that the drive towards digital migration, one might think, was driven more by the technology than by the needs either of the broadcasters or the consumers. That’s the question that seems to me still to hang in the air. Is this technology-led or is it consumer-led, if we wrap into ‘consumers’ both the people who are the end-users and the people who are using the technology to deliver a service?

Mr Davies: I think that is why there are so many caveats around it, because it needs to be, as you say, consumer-led. So, some of the conditions that would need to be met for the figure to come out positive are that coverage needs to be built out, that the content proposition needs to be right, that a lot of the benefit in there is from additional choice for consumers. That is obviously down to industry to provide. That is not something that either government or Ofcom can do. One of the main caveats was the need to roll out the regional layer [of DAB multiplexes] that we were talking about earlier, to become a new national layer, so providing more choice of mass market stations, if you like. So it is absolutely consumer-driven, but where that leads you, I think it is probably too early to say, and, as you say, it is very finely balanced.

Baroness McIntosh of Hudnall: What about your own impact assessment?

Mr Davies: We haven’t done an impact assessment yet.

Baroness McIntosh of Hudnall: But you have been asked to – correct?

Mr Davies: At some point in the future. I think the Digital Britain report said that we would be asked to do one, but we haven’t been asked to do one yet. Obviously we would need to do that and we would need a much fuller cost-benefit analysis before any final decision was taken.

Baroness McIntosh of Hudnall: So that’s a future thing.