Ed Richards, Chief Executive, Ofcom [ER]

Q&A @ Radio 3.0 conference, London (excerpt)

21 May 2009

Q: Isn’ t the big issue with DAB ‘[FM] switchoff’?….

ER: It is one big question but it definitely isn’t the only big question. And the difference with TV is very instructive. One of the profound differences with TV, of course, is that in the case of TV you couldn’t extend Freeview digital television without turning off the analogue spectrum, and that’s a profound difference. One of the other differences, of course, is that the value of the spectrum released by analogue switchoff in television is extremely high. Indeed, people are fighting each other metaphorically to get hold of it and have been ever since we mooted the idea some years ago. So there are some very big differences. The other obvious differences are that people have more radios than they do have TV’s, and so on and so forth. It is a very big question but I don’t think it’s the only one. That is why we put as much emphasis on the inherent sustainability and viability of digital [radio] services. It is always going to be asking people a lot to simply look forward, especially in the context of no switchoff date – and even if there was a switchoff date, it would be some years away – it’s always going to be asking them a lot to take losses for a long period. If only we can get to a point where DAB services are essentially at least breakeven, the better because that gives you a base from which to plan the other more challenging things, which include switchoff, and we want to work quite hard at that alongside the debate about Digital Britain.

Q: Without a date, it feels like it’s almost over the horizon. People I talk to in radio nearly all say ‘what we need is a date’. Is Digital Britain going to give us a date, do you think?

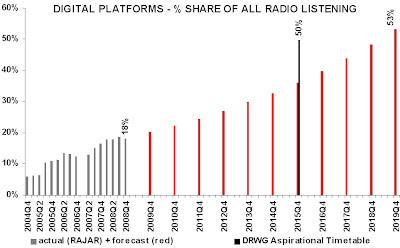

ER: That is a common theme that you hear, it is true. Before answering the thrust of that, I reiterate that I think you need to address the date and the migration issue, but you need to address the underlying economics first and immediately at the same time. And that means a frequency plan, savings in transmission, and so on and so forth, and it means continuing growth and more listeners on DAB. I hear everybody, a lot of people, say that we have to have a date. Will Digital Britain give us a date? I don’t know. There are a number of things we don’t know about Digital Britain yet.

Q: Would it be helpful if it did give us a date?

ER: It depends what the date was. It wouldn’t be helpful if the date was next year. I think the most important thing is … Let me rephrase the question slightly. You can only have a date if you have got a credible plan that delivers that date. So I could give you a date now but it would be meaningless. It would be rather like the television switchover date in one or two countries around the world – which I won’t name because it would get me into trouble – but they name dates, the governments stand up and puff up their chests and name dates but they are meaningless and, as soon as they have left the room, everybody laughs. So a date is meaningless without a credible plan to get there, so I recognise ….

Q: It’s a bit chicken and egg, isn’t it?

ER: Well, you have to have one in order to have the other. I think where people really are on this is, when they say we must have a date, that is another way of saying we must have a credible plan which gives us a date, and I would agree with that ….

Q: But how close are we to a credible plan?

ER: We are getting closer. We are doing a lot of work, as I said in my contribution, around the re-planning and I think the re-planning is very important to it. We need to have a clear set of proposals about quality of service and coverage and all those sorts of things, and those things need to be in place before you can have a credible plan. But there is work actively taking place on that and being driven forward. But better to get that right and to have a sense of urgency and determination, than just to pluck a meaningless date out of the air.

…..

Q: I’m still struggling slightly with [FM] switchoff only because it strikes me that almost everything hinges upon this and what you say is perfectly sensible – you can’t really have switchoff until you have a credible plan – but we know that, in the real world, unless we are forced by one thing or another, we don’t actually face this and businesses are very similar to life and everybody is still hedging their bets on FM. I speak to mobile phone manufacturers who say ‘well, look, we only have room in our phones for so many transmitters and receivers. We have got Bluetooth, we have got infra-red, we have da-da-da-da-da and all our users tell us they really value FM’. So they are not going to switch it until they have to. People with DAB radios in their cars are still a rarity and the manufacturers are not going to start installing them as standard until someone says ‘OK, 2013, 2012, 2011, whatever it is – that’s it’.

ER: Well, that’s the attraction of setting a date and driving everyone to it. But I’m trying to think of something different to say than what I said earlier.

Q: Would you favour it as an option?

ER: If there is a credible plan, yes. You’ve got to have a credible plan. And what you can’t do is just pluck a date out of the air and say ‘we’re all going to get there’ because I know what will happen under those circumstances. What will happen is that it will be fine for about a month and then, going for coffee outside the conference room, everyone will say ‘well, that is not going to happen, is it?’

Q: Except in TV, it has and it is.

ER: In TV, we wrote the original document which said ‘we will push on to digital switchover in this timeframe and here is how you can do it’. We wrote that document and said ‘these are the six of seven things you have to do to deliver it’ and we knew what you had to do to re-plan, we knew what you had to do to lead people across, we knew about the re-tuning, we knew the vast majority of things and there was a plan. That plan was then picked up by the creation of Digital UK, and so on. We’ve got to get to that next step, so I think it’s an exciting prospect but we’ve got to believe that it’s credible and deliverable. So I know that I’m repeating myself and not being particularly helpful but I do genuinely believe that and we need to – senior people in the industry need to sit round, look at this, stare at the steps and say ‘will that deliver it, is it consistent with what is in the audience’s interest?’ There’s no point in doing something which audiences then regard as a disaster. We have to do something that audiences, as it took place, will regard as a good thing. That’s an acid test and I think that’s possible, but there’s a lot of work to do and we’ve got to see if we can get there.