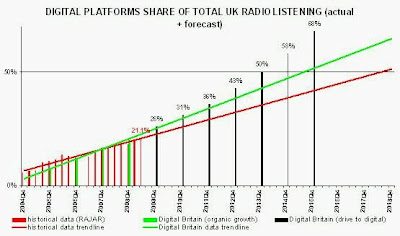

Today’s RAJAR data demonstrates that a gulf is opening up between BBC radio and commercial radio in their ability to attract listening to digital platforms. Over the last year, the BBC is accelerating away from commercial radio in its audience’s usage of DAB, digital television and the internet to listen to live radio programmes. The significance of this growing gulf is reinforced when one remembers that the main RAJAR survey, from which the data below is taken, only measures ‘live’ radio listening and does not incorporate listening to either time-shifted, on-demand radio (‘listen again’) or to downloaded podcasts, both forms in which the BBC offers a much greater volume of content than UK commercial radio.

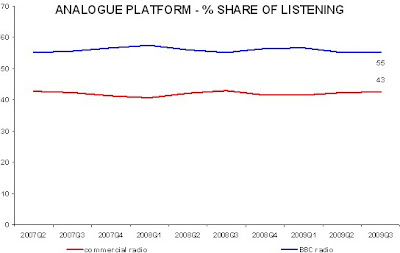

The danger here is that the BBC is poised to dominate listening on digital radio platforms in the long term, exactly as it already dominates listening on analogue radio platforms. One of the main reasons that the commercial radio sector invested so heavily in digital platforms during the last decade was the opportunity it offered to compete more effectively with the BBC for audiences. In the analogue world, the commercial sector has always argued that the BBC (having been there first) was allocated more and better spectrum for its radio stations. ‘Digital’, particularly DAB, seemed to offer the commercial sector a chance to ‘even the score’ with the BBC. The RAJAR data show that this ambition is not succeeding.

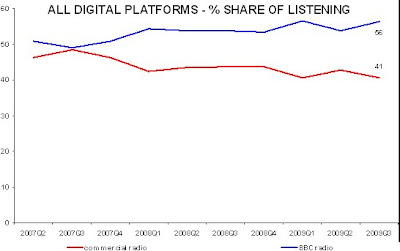

Across all digital platforms aggregated, commercial radio is losing ground, with the latest quarter (Q3 2009) reducing its share of listening to 41%, versus the BBC’s 56% share.

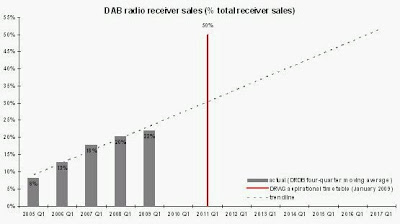

Taking each digital platform in turn, commercial radio’s share of listening on the DAB platform fell to 33% in Q3 2009, compared to the BBC’s 65%. This is not surprising because the age profile of DAB purchasers tends to be older listeners who are statistically more likely to listen to BBC stations. However, it does pose a grave question as to the return that commercial radio can expect from its substantial investment to date in DAB infrastructure, if listening on that platform is dominated so much by the BBC.

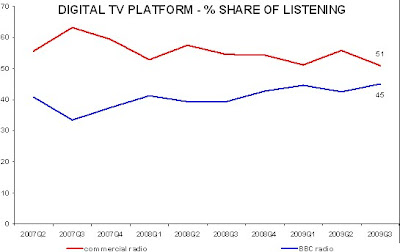

The digital TV platform is one that commercial radio has long dominated because of the large amount of spectrum it leased in the early days of Freeview. However, the increasing popularity of digital terrestrial television has already substantially increased the cost of spectrum on Freeview for the radio industry when its contracts come up for renewal. Furthermore, the forthcoming re-ordering of the multiplexes to accommodate HD television and new compression codecs is likely to squeeze commercial radio’s access to Freeview spectrum even more so. Before long, it is likely that the BBC will dominate the digital TV platform, just as it already does on DAB. Presently, the BBC has a 45% share, compared to commercial radio’s 51%.

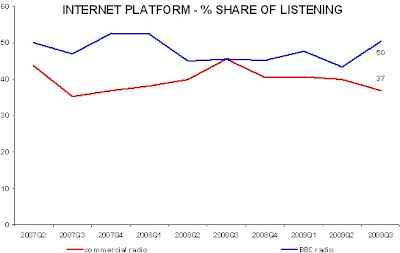

As might be expected, the BBC’s strong online presence has already put it in the commanding position in terms of its share of listening via the internet platform. The integration of BBC radio into the iPlayer has no doubt helped as well, whereas commercial radio’s offerings are relatively more fractured and less heavily marketed, despite the excellent innovation of the RadioCentre Player. The BBC has a 50% share of listening on the internet platform, compared to commercial radio’s 37%.

The significance of commercial radio’s diminishing share of these three digital platforms is demonstrated when we look at the two sectors’ listening shares achieved on the analogue platform alone. Once one removes the digital platforms from the picture, it is evident that the shares of both the BBC and commercial radio have remained relatively stable in recent years. In other words, it is commercial radio’s declining share of listening on digital platforms that is effectively pulling the sector’s total share of listening (analogue + digital) down, particularly as digital platforms are growing as a proportion of total radio listening (21.1% in Q3 2009).

There is a paradox here. The commercial sector invested heavily in the DAB platform, believing that the new technologies would help it INCREASE its overall share of radio listening versus the BBC. In fact, that investment has recently helped to DIMINISH commercial radio’s overall share of listening. Digital television remains the only platform in which commercial radio dominates, and yet this is the very platform where commercial radio will be forced to cede spectrum and face, once more, losing out to the BBC whose spectrum for radio is guaranteed.

It is important to emphasise that these graphs show only the SHARE of listening on these platforms. The volumes of listening on each of these platforms have demonstrated absolute growth for both commercial radio and for the BBC over the same time period. But, more than any other digital platform, it is significant that the DAB platform is dominated by the BBC which now accounts for almost two-thirds of its usage. Such data is important when making decisions about the potential returns on further investments in DAB infrastructure. Will further investment simply maintain the existing imbalance, or will it really improve commercial radio’s share? Does investment in infrastructure also require parallel investment in new content that will appeal directly to the older age groups who own DAB radios?

Some possible reasons for commercial radio’s diminishing share of listening on digital platforms include:

• Commercial radio’s tendency to invest in DAB infrastructure more significantly than in original digital-only content

• Recent closures of many digital-only radio stations in the commercial sector

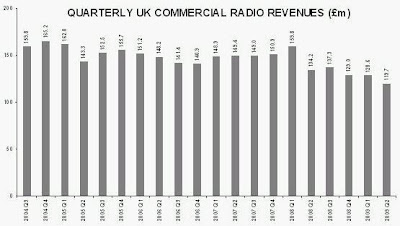

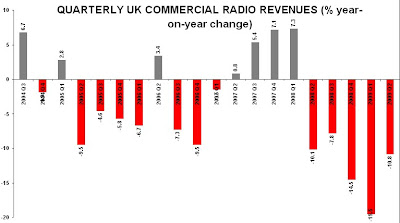

• The BBC’s relatively stable resource base, at a time when commercial radio revenues are falling precipitously

• The BBC’s long-held policy to invest simultaneously in multiple platforms, whereas commercial radio has focused on DAB and, to a lesser extent, Freeview

• The BBC’s focus on creating exclusive digital-only content unavailable on the analogue platform

• The BBC’s 360-degree music royalty agreements which allow it to use diverse platforms, whereas commercial radio requires separate (and more restrictive) agreements for time-shifted content and podcasts

• The BBC’s long-term, consistent promotion of content and digital platforms across TV, radio and the internet whereas commercial radio is less willing to cross-promote content or digital platforms that migrate listeners away from its core analogue offerings

• Frequent management changes and ownership changes in some parts of commercial radio, where substantial consolidation has often translated into short-term ‘slash and burn’ rather than ‘invest and build’ policies.

Whatever the reasons, we are not where we were meant to be – that is, we are not where it had been anticipated more than a decade ago commercial radio would be when investment in digital platforms, notably DAB, was expected to produce a beneficial outcome for commercial radio audiences versus the BBC. To put it plainly, the strategy conceived in the 1990’s has not worked. Commercial radio offerings do not dominate digital platforms (yes, they are more numerous, but they do not attract more hours listened than the BBC). DAB has become a largely BBC platform.

So, what can be done? Some of the issues noted above require a more level playing field to be established between commercial radio and the BBC. One such example of a practical solution is the Radio Council plan for a new UK Radio Player that will offer BBC and commercial radio content from a single aggregated access point. Other issues remain mostly in the lap of the gods (revenues, for example). Some issues require the BBC to be less predatory (or more regulated) and for the commercial sector to be more focused on strategic, long-term objectives (such as an online strategy that is more than simulcasting).

There is no single answer to this complex problem, though the commercial radio sector is hobbled by both its present lack of profitability and the regulatory strings that are attached to the majority of its analogue radio licences. What is desperately needed in these difficult times is not minor regulatory tinkering (such as adjusting how many hours of local content a local station is required to broadcast) but a wholesale change in strategy to maintain a commercial radio sector that can thrive in the digital marketplace we now inhabit. Will the imminent Digital Economy Bill prove sufficiently forward-thinking in its radio policy proposals?

[Statistical note: The graphs above to do not sum to 100% because the minimal amount of platform data released by RAJAR is ‘rounded’ (hours listened to 1,000,000; listening shares to 0.1%) and the listening apportioned to the BBC and commercial radio sometimes does not add up to the total for a platform. Some of this shortfall may be accounted for by ‘other’ listening (neither the BBC nor commercial radio) which is not itemised by platform. Data for individual quarters are therefore somewhat inconsistent, though the trend over several quarters is likely to be indicative. Additionally, there is an element of radio listening unattributed to any platform, 12.8% of the total in Q3 2009, but which is roughly equally applicable to BBC radio and commercial radio.]