On Wednesday 10 December, Lord Carter told the Parliamentary Culture, Media & Sport Committee:

“Radio can be received on mobile phones and through the television. Could you have digital radio without DAB? Yes, you probably could. If we do want DAB, we need to push it along a bit or technology will drive it out”.

“Push it along a bit” probably means state intervention and/or state subsidy.

“Technology will drive it out” probably means technologies such as IP-delivered radio via the internet, Wi-Fi, Wi-Max, 3G and 4G, as well as broadcast radio delivered via Freeview, Freesat, Sky and cable.

The same day, evidence was published that demonstrates how one of these platforms – internet-delivered radio – is already poised to eclipse DAB radio. “With broadband internet access rising from 51% of UK households in 2007 to 56% in 2008 and the high profile launch of the BBC iPlayer, listening to the radio online has never been easier or more popular”, said the new RAJAR internet radio listening report. Its definition of internet listening is:

- listening live via the internet

- listening again via the internet

- personalised online radio

- podcasts.

The most informative graph in the RAJAR report was the one that wasn’t there….. the one that compares the weekly adult (15+) reach of the DAB platform with the internet platform:

Unfortunately, usage data for the DAB platform is not available on a comparable basis prior to Q2 2007. Suffice to say that commercial radio launched its national Digital One DAB multiplex on 15 November 1999, which could be considered “Year Zero” for DAB (although it was some time before DAB receivers filtered into shops). What is startling is that the reach of internet radio is so close behind that of DAB. If you were to add up the market value of all the marketing spots promoting the DAB platform that have run on BBC TV and radio and commercial radio over the last decade, their total would run into £m. Add the cost of the sterling efforts of the Digital Radio Development Bureau, jointly funded by the BBC and commercial radio, since 2001 to convince us of the value of DAB radio.

Now compare this with the marketing cost to date spent persuading us to listen to radio via the internet (lots of mentions within BBC radio programmes, but fewer on commercial radio), and it pales by comparison. And yet, listening via the internet is way up there, just behind DAB, driven largely by consumer demand rather than by public intervention.

The other interesting statistic in the RAJAR report was the glaring difference between the online impact of the BBC and the commercial radio sector. Of those who listen to radio via the internet,

- 71% listen via a BBC radio website

- 25% listen via a UK commercial radio website

- 13% listen via a non-BBC, non-UK commercial radio website

This merely confirms something that was evident already – in the 1990s, the biggest players in the UK commercial radio industry decided to put all their ‘future of radio’ eggs in the ‘DAB’ basket and, as a result, neglected to make a comparable investment in the online platform. The BBC has been much more careful (and, admittedly, has the immense resources available) to develop content across a number of platforms simultaneously, and is now reaping the return. Commercial radio could have developed its own ‘last.fm’ but chose instead to invest huge sums in the DAB platform infrastructure, rather than content, and is now paying the price.

Lord Carter will have to make a difficult (and potentially expensive) political recommendation between now and January 2009 about the future of the DAB platform:

OPTION 1 – Massive state financial intervention to prop up the expensive DAB transmission infrastructure. Who benefits? UK industry. The end result is a closed, almost UK-exclusive system (just like right-hand drive cars). UK radio set manufacturers sell lots of DAB radios in the UK because it is not worthwhile for the global consumer electronics groups to manufacture DAB radios for such a small addressable market. The large UK commercial radio groups and the BBC benefit because they already own both the entire DAB multiplex infrastructure and most of the content broadcast on it, ensuring that most radio listening in the UK remains under their control. Who loses? The consumer. They get a marginally increased choice of radio content that, so far, has failed to propel the DAB platform to mass take-up.

OPTION 2 – No state intervention to support the DAB platform. Who loses? UK industry. DAB remains economically unviable (just as it has been for a decade), forcing commercial radio groups to withdraw from the platform (with substantial balance sheet write-downs). DAB becomes the province of the BBC to offer minority interest services. UK radio set manufacturers lose most of their promised UK market for DAB radios. 7m DAB radio owners complain to Ofcom that all they can receive now on DAB are BBC stations. End result. The UK joins the rest of the world in accepting that IP-delivered radio is an emerging global platform from which the UK benefits from economies of scale (cheap receivers, evolution and innovation). The UK has to admit that DAB seemed like a promising technology in the pre-broadband late 1980s, but its slow implementation was overtaken by technological developments elsewhere and the globalisation of content.

As recently as 2004, The Guardian reported:

“The DTI hopes digital radio will become a rare British industry success story; Ofcom thinks it could get some juicy spectrum to sell off; manufacturers and retailers see rich pickings (“the flat-screen TV of tomorrow”, as the man from Dixons told me). Everyone, that is, except the British consumer, who is showing worrying signs of being dazzled by the new technology. According to Stephen Carter, Ofcom chief executive and digital radio owner, most Britons would be on my wife’s side – pretty sure that DAB is a good thing, but not quite sure what it is. Last Thursday, in a drum-beating speech to the Social Market Foundation, Carter described the radio industry’s foray into digital platforms as at a tipping point between a Sky-style digital success story and an industry-wide egg-on-face scenario.”

Four years later, are we any more certain about DAB? There may be a lesson to be learnt from Taiwan:

“The development of DAB in Taiwan passed through three stages: planning, preparation and a final stage characterized by setbacks. It now looks like it may disappear altogether…… After two years of trials, DAB experienced problems, partly because of a lack of promotion, inadequate public knowledge of the technology and high-priced DAB radios that few were willing to purchase. As a result there were too few consumers to keep DAB up and running. In July this year, Taiwan Mobile announced that Tai Yi would be dissolved, and the outlook for other DAB providers is not very bright. The biggest problem for Taiwan’s DAB industry was a lack of forward-looking policies……”

How likely is this outcome???

How likely is this outcome???

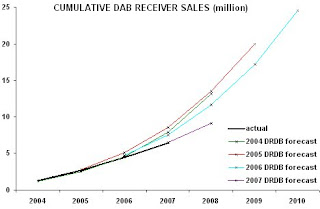

This last graph is interesting because the Digital Radio Development Bureau published progressively less optimistic annual forecasts for DAB set sales in 2004, 2005, 2006 and 2007. Its 2007 forecast only projected figures to 2008. When I enquired in September 2007 why the forecast horizon had been reduced by three years, the DRDB told me:

This last graph is interesting because the Digital Radio Development Bureau published progressively less optimistic annual forecasts for DAB set sales in 2004, 2005, 2006 and 2007. Its 2007 forecast only projected figures to 2008. When I enquired in September 2007 why the forecast horizon had been reduced by three years, the DRDB told me: