At the Radio Festival in Nottingham, the final session on Wednesday 1 July 2009 @ 1215 was a discussion about the future of UK radio that was broadcast live on BBC Radio 4’s Media Show and hosted by Steve Hewlett. Part of the discussion was about DAB in the UK following the publication last month of the Digital Britain report.

Amongst its range of proposals, Digital Britain had recommended:

· “at a national level, we will look to the BBC to begin an aggressive roll-out of its [DAB] national multiplex to ensure its national digital radio services achieve coverage comparable to FM by the end of 2014”

· “where possible, the BBC and national commercial multiplex operator should work together to ensure that any new transmitters benefit both BBC and commercial multiplexes”

· “further investment is required if local DAB is ever to compare with existing local FM coverage”

How will this improved DAB infrastructure be paid for? Digital Britain had suggested:

· in some geographical areas, “the BBC will need to bear a significant portion of the costs”

· “however, the full cost cannot be left to the BBC alone”

· “some [commercial radio] cost-savings must support future [DAB] transmitter investment by the local multiplex providers”

· “the investment needed to achieve the Digital Radio Upgrade timetable will on the whole be made by the existing radio companies”

Interviewed about these issues for the Media Show were:

Tim Davie, Director of Audio & Music, BBC [TD]

Phil Riley, former Chief Executive, Chrysalis Radio [PR]

[Tim, where is this money coming from?]

TD: The truth is that I can’t say I can find it. What I have been saying very clearly is that I can make a case for it. And, where the money comes, or could come, from I think is pretty well articulated in public debate, which is… We have been spending money against broader digital distribution projects – the digital television switchover – and where we spend the Licence Fee beyond content, it’s this thing called the ring fenced fund where we’ve been investing in digital television switchover. Now, as the radio guy, it’s saying ‘we have a case for this medium’. We love radio. We think there’s a really good case for it being there as an investment ….

[This investment has got to happen pretty quickly to stand any chance of getting us to the 2015 date which the government have set us as their target for switching from analogue to DAB. That means quite a lot of things have got to happen by 2013. That’s into the next Licence Fee settlement. So you need to find £100m for your 600 extra [DAB] transmitters, or whatever it is, in this settlement. Have you got it?]

TD: Well, we have said that we don’t think – and we’re yet to see what that looks like because we haven’t done TV switchover that ….

[Have you got the money? You have to start spending now, you can’t leave it because [otherwise] you’re never going to get there, are you?]

TD: We’ve said that as part of Digital Britain – it’s all in the report – it says that in the course of the next 12 months, even if we wanted to spend money at this point, we don’t quite know what we are spending it on. Without getting too technical, if you look at the ….

[On ‘Feedback’, you’ve said 600 transmitters are needed to get to an equivalent coverage of FM and you said the BBC wouldn’t go there unless coverage was roughly equivalent to FM.]

TD: Specifically, the minority of money is those 600 transmitters that gets you on the national multiplex, which is what the big stations like Radio 4 go on, that gets you to 98% cover. The bigger money is in sorting out the regional and local stations which are a bit of a patchwork and that investment – the numbers are loose because we are going to be doing some detailed planning with the commercial sector on ….

[Very briefly, a one-word answer. Do you have any money set aside now to spend on this purpose?]

TD: No.

[Splendid.]

………………………..

[Does commercial radio have any money to spend on this proposal?]

PR: If you read the Digital Britain report in its totality, there are a number of proposals for changing the way commercial radio operates, in terms of co-location and regional licences becoming national networks. Now, bringing all of that together as a piece, will that free up sufficient additional funds for the commercial sector to be able to roll out more digital? I don’t know. You’ll have to ask the other commercial players.

[What’s your guess?]

PR: ‘No’ is the answer at the moment.

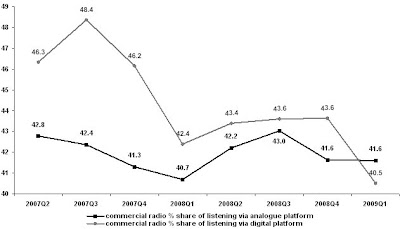

[Because one of the issues with DAB surely is that the commercial side of the equation has already, in commercial terms, failed. Increased costs, but no increased revenues. Not even Channel 4 was able to galvanise it to make it change. Is there a commercial model in DAB at all, do you think?]

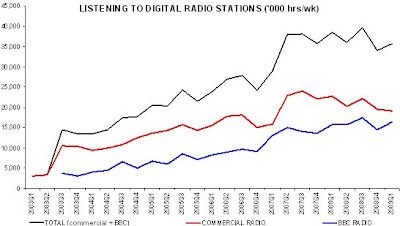

PR: I think DAB is a terrific platform. The die has been cast. 9 million sets, 20% of all listening. DAB is here to stay. So, we can’t go back to not having DAB so actually we’ve got to go forward and we’ve got to go forward with as sufficient a pace as we can. My concern would be trying to go forward too fast and falling over ourselves.

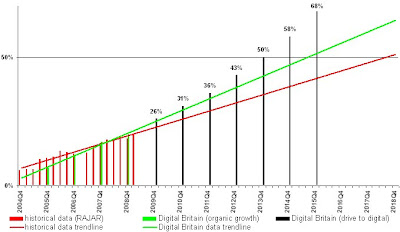

[The government has said they want to do this in 2015. They have said that by 2013 they won’t press the button to switch off [FM] until …. They will give 2 years’ notice. So, by 2013, I think they want 50% of listening to be on DAB, and 90%+ coverage of DAB across the country. Is that timetable in any way realistic? The BBC say they have no money set aside just now. You say that you don’t. How’s it going to happen?]

PR: I think Tim famously used the euphemism ‘ambitious’ yesterday and I think ‘ambitious’ is the right word for it. Personally, I can’t see us getting to 2013 although, to be fair to the Digital Britain report, it says it will test it every year from 2013 and when we get there, then we will move on to Phase Two.

[Tim, lots and lots of listeners have contacted this programme and other programmes whenever they have been asked and are very very worried about this. They think they might have 3, 4, 5, 10 – 15 in one case – analogue radio sets and they have been asked to go through all the rigmarole of changing them and ‘what for?’ is the question they ask. ‘Why are you asking me to do this? It’s not broke, don’t fix it’.]

TD: If you look at the industry as a whole, you could argue that we are not ready for the future. Actually, although we have some fantastic services on-air now, we have just talked about commercial radio – their financial model looks pretty broken at this point.

[Isn’t the key question ‘content’?]

TD: I think the case to the listener is really clear, which is – digital radio can present a much wider range of national stations, it can offer functional benefits. We’ve seen what that can bring in something like television. There is a real challenge for the industry to step up to the plate and deliver that content, and that has to happen. And, to be very clear, I am very worried, like the listeners, that if you have all these old [analogue radio] sets and there is no benefit, we should not be moving. What’s happened in the last few weeks though, and months, is that the radio industry as a whole has said ‘we’re going to go for DAB and we’re going to try the transition to digital’. We haven’t said that it is actually happening until we’ve earnt that, which will be at a threshold level.