When something works well, it just works. You do not need to analyse why it works. It just works. And nobody asks questions as to why or how. That is the case with FM radio. During half a century of development, more and more FM transmitters have been built across the UK (2,100 currently in operation) so as to reach the point now where almost the entire population receives an FM signal (maybe not always perfect, but some reception rather than none at all).

DAB radio was intended to replace FM radio. However, it must only be worth replacing FM with DAB if DAB is actually better than FM. Why replace a transmission system that has taken 50 years to perfect with something that is going to be worse? Unfortunately, nobody thought to conduct a cost/benefit analysis during the last two decades to determine what the cost would be of making DAB radio reception as good as FM radio, let alone better. As a result, DAB radio was foisted upon the public in 1999 without a roadmap to ensure that reception was even as good as FM radio for consumers.

Twelve years later, DAB reception remains worse than FM reception in many places, or is non-existent. Whereas poor FM reception gives the consumer a poor quality listening experience, poor DAB reception provides no listening experience whatsoever. With DAB, a poor signal is the same as no signal.

Instead of Ofcom valiantly admitting defeat over DAB radio – which might infer that the regulator and its predecessor, the Radio Authority, had screwed up the implementation of DAB in the UK – Ofcom presses ahead with increasingly desperate attempts to try and salvage this technological and regulatory disaster.

Ofcom’s latest ‘project’ is to try and understand why FM radio, more than half a century after its introduction, gives consumers acceptable radio reception. Intrinsically, the work is redundant. If FM works well, why bother to analyse why it works? The answer is: because DAB radio does not work. In order to make DAB work, an understanding is deemed necessary of why the system it was intended to replace – FM radio – does work.

Belatedly, it has been understood by the bureaucrats that the expense of making DAB as good as FM will prove too costly. It requires too many DAB transmitters, too many DAB power increases, at too great a cost for the radio industry. Might this not be a good time for them to back away from the notion of DAB radio REPLACING FM radio because it is simply too costly, even just to make it AS GOOD?

Not for the bureaucrats involved. Instead, the philosophy within Ofcom and the government is a new plan to deliberately make DAB radio NOT AS GOOD as FM radio. But still to persuade consumers that DAB is intended to replace FM radio for national and large local radio stations. Madness? Yes. Self-defeating? Yes. Contempt for radio listeners? Totally.

Peter Davies, who is responsible for radio at Ofcom, explained part of this 1984-style philosophy to replace ‘good’ FM with ‘worse’ DAB to the Digital Radio Stakeholders Group meeting in the calmest of tones on 3 February 2011. Although his presentation is lengthy, I have included Davies’ words in full below so that you too can try and decipher the logic of a solution for DAB radio that is purposefully sub-par.

Perhaps the Digital Radio UK marketing slogan next winter will be: ‘Buy a DAB radio! Worse reception than FM guaranteed. But better than no radio at all.’

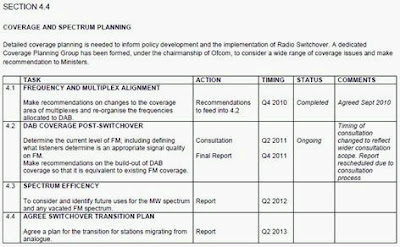

Peter Davies, Ofcom: “The Coverage Planning Working Group is chaired by Ofcom, but we have effectively two groups that are feeding into this. There is the actual Working Group that is doing all the sort of hard grind of doing the planning work, and that consists of Ofcom, Arqiva and the BBC. There is also a Planning Advisory Group which consists of all the [DAB] multiplex operators, with Digital Radio UK and RadioCentre as well. So what I’m going to run you through this afternoon, quite quickly because of the time, is just what we’re doing in terms of FM. What is it we are trying to match? Secondly, how you then do that with DAB. Thirdly, looking at what we need to do to the frequency plan in the UK to achieve that. And then just onto the next steps.

So, FM coverage. I should say we are doing this for national services as well as local. So it’s both BBC and commercial national services, as well as the local. But I’m going to focus this afternoon on the local because that’s, in a way, where some of the more difficult issues are. This is a map of Manchester. I know you won’t be able to see the detail on that, but it gives you an impression, at least. So what we’ve done in each part – in fact, in the whole country – is define a set of ‘editorial areas.’ So that’s shown on this map by that dotted line – you can see around the edge, a sort of dark purple dotted line – so that everywhere in the country is covered by one or more areas – there are some overlaps – but at least everywhere is covered by one area. So the editorial areas are areas that have been agreed by the BBC and by the [DAB] multiplex operator and commercial radio operators as being the sort of area that they would, in an ideal world, like to cover. It’s also based on [DAB] multiplex areas, so it’s a bit of a compromise.

So, if you look at the actual coverage of BBC Radio Manchester [GMR] within this, that’s shown in the sort of standard way of measuring – 54 db – is shown in green but, actually, editorially BBC Radio Manchester would like to cover the bits within the dotted line. So there is coverage beyond the editorial area where people can pick up the service, but it’s not really intended for them. And, equally, there are bits within the existing editorial area which aren’t covered terribly well on FM but which, nevertheless, the station would like to think it serves.

In terms of the actual [FM] coverage, it’s been quite difficult to determine what that is. The ‘54db’ is the standard internationally agreed planning measure. So that’s 54db per μv per metre, but I’m not an engineer so don’t ask me any more detail than that. But it’s a definition that was drawn up back in the 1950s and is really about reception 10m above the ground, using a rooftop aerial and it sort of tells you whether you can get a signal on your radiogram, which is not terribly useful [now]. So we know that people use radios in very different ways, but we sort of know that this works, but it has never actually been tested. So it’s a planning definition, which is very old and slightly messy.

So what we’ve been doing as part of this work is drawing up what’s known as a ‘link budget ‘, which is effectively taking the signal strength as it leaves the transmitter and then adjusting it all the way along until it actually gets to the receiver. So, in other words, you adjust it because it’s a distance from the transmitter going over some hilly ground, going down into buildings, loss within the receiver itself and so on. So that you can work out what signal strength you will need to work to get decent FM coverage. So we’ve looked at three different strengths because we know that the 54db is probably a little bit conservative, so we also looked at 48db and 42db, again because conditions vary between what you can receive on a portable kitchen radio and what you can get in your car. We are also looking at coverage not only of households, but also of major roads as well, so it’s not just an indoor measurement we’re looking at.

What we have seen so far is actually that the link budget we have developed is that these numbers are probably about right. So 42db is probably about right for cars. But you can see that there’s not actually very much yellow on that map, so that most places either get a good solid indoor signal, or the signal’s not good at all, basically. So, for each area, we have looked at both the BBC local service – so that’s BBC Manchester – and also the commercial coverage, and we’ve taken the largest commercial station in each area. So, for Manchester, this is ‘Key 103.’ As you can see, the coverage is very different, mainly because they are using different transmitter sites and different powers on FM. But, of course, both of those services and others are on the same multiplex for DAB, so you have to think ‘what exactly is it on FM that we are trying to match?’ It’s no good just matching Key 103, you can’t just match to Key 103 because then you would be missing out BBC Manchester and other services. In this case, commercial [radio coverage] is smaller. In other cases that we have looked at, the commercial [stations] cover one part of the county but not another, but the BBC [station] will do the opposite.

So, what we’ve then done is to look at the composite coverage of both BBC local [radio] and the largest commercial station. So this is what we think people in the area would expect to be able to hear as a local service on FM. So you get either the BBC or the commercial radio [station] or both. So that’s the basis of what we think we should be trying to match. So it would be sort of green or blue for indoor, and the yellow bits for road coverage. As I say, we’ve done that for basically every area in the country, including the Nations services – so Radio Scotland, Radio Wales, etc for the BBC – and for the national services as well.

The question then is ‘how do we match DAB [to FM]?’ So the approach to that again has been to build up a link budget for DAB, starting with the transmitter and going right the way through to the receiver. And we’ve been doing receiver tests as part of that. And what we tried to do – because that sort of coverage is slightly debatable on FM – is [identify] where exactly is that band, and where exactly is that field strength? The approach we have taken is, first of all, to say that, within the editorial area, let’s plan for absolutely universal coverage. So how many transmitters – if you wanted to cover it as near as possible to 100% – how many transmitters would you need, both to get indoor coverage and road coverage as well? And we’ve tried to do that in a sort of commonsense way by starting with where the existing FM transmitters are. So rather than just look for new sites, because actually if coverage from FM is good from that site, so you should get decent coverage from DAB from that site as well. And then we’ve added on transmitters at decreasing levels of coverage until you get as close as we can to 100%.

Then, once we’ve done that, we’ve said ‘okay, actually some of those are now covering areas which aren’t covered by FM’ so actually you might not need them. So then you can then sort of roll back from that full universal coverage. The question then is ‘where do you draw the line?’ So, if you look at Manchester. Again, you’ve got the editorial area, which is a bit hard to see on this, but is the solid purple line around the edge. That is the existing local DAB coverage in Manchester, so you see 66.4% of households at the moment. In terms of households [for FM coverage], we have got 96.2% indoor at the moment, 98.2% (that’s a slightly sort of spurious measurement because it’s not actually a road measurement, but it’s households), so 96.2% for FM. So 66.4% existing [DAB] coverage from the two transmitters which are currently operating from the Manchester multiplex. It is one in central Manchester – sort of there – and there is one at Winter Hill at the top in the northwest corner.

We then looked at ‘okay, what would you do if you just increased the power of the existing transmitters and moved them up the mast a bit?’ And, actually, that gets you, as you can see, quite significantly increased coverage. In order to do that, we need to change the frequency plan, and I’ll come back to that in a minute. So that gets you up to 82% [DAB coverage] and then we keep adding on transmitters until we get as close as we can to 100%. This goes to 99% and that means 15 transmitters which are shown by the crosses dotted all over that map.

But then, as I say, you look at it and you say ‘well, actually, the two smallest of these – which are these two up here – actually have no household coverage at all, and the smallest one only adds 8km of road coverage.’ Now, obviously, if you’re driving and you lose your radio reception, then that’s a problem. But there’s a question as to whether that is essential for local coverage – it might be for national, but is it for local? So the question is ‘where do you draw that line in terms of a sort of cost/benefit analysis,’ if you like? You might decide, actually, you wouldn’t bother with those, but the question is ‘how far down the list of 15 [transmitters] do you go,’ as to what’s commercial viable and what provides an acceptable level of service to consumers?

So that’s the approach that we’ve taken. As I say, in order to do that, we need to change the frequency plan. Those are the big [frequency] blocks we use for DAB at the moment, dotted around the country. And you can see that they – the colours represent frequencies – so you can see that we have to reuse the same frequencies over and over again around the country. And that does cause interference so, at the moment, Manchester uses the same frequency as Birmingham. And, because of that, we can’t increase the power of the Manchester transmitters to get beyond that 66% to the 82% [coverage]. And that problem is repeated around the country. So what we’d like to do is re-draw the frequency map, which means that, as far as consumers are concerned, means doing a re-scan of their radio but does then allow us to boost the coverage quite significantly from existing transmitters and reduces that problem of interference which, in same places, can be quite significant. In order to that, it’s quite a long process – we need international co-ordination – but that part of the planning process we are going through at the moment.

So, the next steps are to finalise that frequency plan and begin the international co-ordination. We’ve got to complete the FM coverage maps and just check that link budget for FM, both for local and national [stations]. And then, for each of the local DAB areas and for the BBC national multiplex and for Digital One, the commercial multiplex, to produce the coverage maps and the household count and the road count as well for all of these existing multiplexes. Once we have done all of that, we plan to publish the whole thing later in the spring or early summer in a consultation so that we can then begin a debate as to whether this approach is actually right or not, and where it gets us.

Obviously, one of the big questions in all of that is actually ‘how much does it cost the broadcasters?’ I should say that that’s not something the Coverage Planning Group is looking at. It’s not something that we’ve been asked to look at, so it’s purely a technical approach at this stage but we think, sort of by the end of April, we should have the answers of how many extra transmitters you would need in order to achieve switchover.”

So the overarching question posed by the forthcoming Ofcom consultation seems to be: how poor can DAB coverage be made but still be accepted by consumers? If Peter Davies’ workplan, as explained here in February 2011, sounds vaguely familiar, it might be because he had addressed the Radio Festival in July 2008 and promised:

“Once we have defined what existing DAB coverage is, we then have to work out what it would take to get existing DAB coverage up to the level of existing FM coverage. Now, we have already done a lot of work on this, and certainly enough to inform the interim report, and the whole thing will be finalised in time for the Digital Radio Working Group final report later this year.” [see Dec 2008 blog]

Incredibly, three years late[r], the promised work is only just being completed. An amazing lack of urgency has been demonstrated by Ofcom, despite DAB radio resulting in more correspondence from angry consumers to the broadcasting minister Ed Vaizey than any other issue.

What most astonishes me is that the digital radio sector is still trying to persuade people living in Manchester to purchase a DAB radio, just as it has for the last twelve years, when it knows that there is a one-in-three chance that a Manchester household will be unable to receive ANY local stations via DAB, according to Davies. I assume a similar situation prevails in other cities.

Time for a class action by disappointed DAB radio receiver buyers?

[no accompanying graphics because DCMS explained: “Peter Davies’ Ofcom presentation is not attached as the content is still work in progress. Ofcom plan to publish all of the data later in the year.”]