The Bomb Squad arrived in vans, ran into the Holborn office block and up its staircase to the eighth floor. We watched events unfold from the car park below, the assembly point to which our organisation of forty-odd people had been evacuated an hour earlier.

That humdrum morning had been interrupted by a large cardboard box delivered by Royal Mail to our office. It was not particularly heavy but had lots of stamps on the outside with a ‘Belfast’ postmark. If you were a celebrity or public figure whose opinions were widely distributed, you might anticipate threats would occasionally be made against your life. If you had a desk job in a little-known British government quango, your greatest work challenge might normally be choosing where to lunch. However, that morning, the box’s addressee Soo Williams was taking no chances. The emergency services were called.

Eventually, the ‘suspicious package’ was removed by ordnance experts and exploded elsewhere. It was found to contain nothing but paper. Printed petitions signed by hundreds of Belfast citizens demanding that religious community radio stations be licensed locally. Williams’ name had been written on the box due to her recent promotion by The Radio Authority to manage the launch of ‘community radio’. Returning to our desks after the false alarm, I ruminated what those god-fearing citizens who had toiled to gather so many signatures might have thought of having been suspected by the recipient of being terrorists.

That morning’s event exemplified the disconnect between the regulator of the radio industry and the public it was supposed to serve. Someone with an interest in the UK community radio movement would have known that tiny unlicensed radio stations had existed for years on both sides of the Irish border, broadcasting church services and information to their communities. Indeed, one history argues that the Catholic Church in Ireland was “the world’s largest pirate radio operator”. However, few of The Radio Authority’s desk-bound administrators demonstrated interest in the medium they were employed to regulate. I was the only employee to have worked in a community radio station (licensed in a 1970’s experiment), having been a founder member of the Community Radio Association two decades previously. But now, within this dysfunctional workplace, I was regarded as the office junior … at the age of forty-four.

Back at my desk, I returned to taking regular phone calls from members of the public dissatisfied with the new-fangled DAB ‘digital radio’ receiver they had just purchased. I never quite understood why the switchboard regularly passed such calls to me, as I bore no responsibility for DAB radio, and my colleagues in the Development office suffered no such impositions. It was already self-evident to me that the rollout of this new radio technology had been disastrous for listeners, though I was expected to defend the system, and worse … to blame the listener for its inadequacies.

Staff were issued with a ‘helpful’ sheet of topics to raise with complainants about DAB. Suggestions to be made to members of the public experiencing difficulties tuning into stations on their new receiver included:

- move your radio nearer a window

- listen to the radio in an upstairs room

- your residence might be constructed of the wrong materials

- your residence might be located in a valley

- your residence might be located in a dense urban area

- your residence might be in an apartment block or a basement

- you may need to install a rooftop antenna.

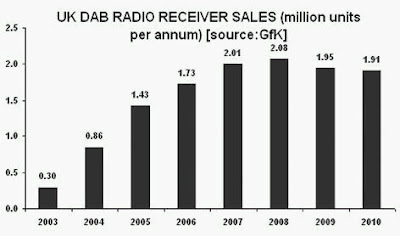

Many callers were understandably baffled and annoyed by these ‘answers’ to their problems, proffering a torrent of abuse or hanging up. Many had spent around £90 on a portable DAB receiver and expected it to deliver what the industry’s marketing had promised – ‘crystal clear’ reception of a wide choice of radio stations. The most popular receiver, the ‘Pure Evoke-1’, had been designed to be portable and had no socket to even attach the suggested external antenna, let alone the connectivity to update and improve its software. And why did it resemble a wooden post-war radio in an era when connected mobile phones were looking increasingly futuristic?

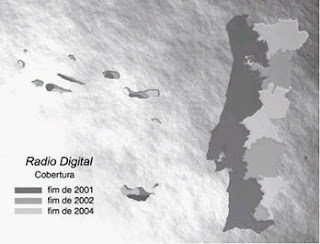

One of my callers’ commonest gripes was the result of DAB radios having been marketed and sold nationwide, even though many parts of Britain had yet to be connected to the DAB transmission system. In this instance, all I could suggest was that the consumer return their receiver to the shop and demand a refund because no digital stations were yet audible locally. I too shared this problem because, although The Radio Authority had denied me its Christmas cash bonus in 2002, I had received the DAB radio gifted to all staff. It remained in its box as I was living in Brighton, where DAB transmissions had yet to arrive.

The root of the dissatisfaction with DAB radio was not the technology itself, which had been a smart European innovation, but the way it had been implemented by Britain. Those critical roll-out decisions had been made by people like the ones in my workplace: administrators who had no experience working within the radio industry, encouraged by technologists keen to promote anything ‘digital’ with an evangelical fervour, oblivious as to whether consumer demand was evident. At the top of this unholy group of conspirators were government civil servants who mistakenly believed that Britain and British industry could dominate global markets by adopting a technological standard in which the rest of the world had shown scant interest. Meetings of this cabal seem to have merely intensified their cult-like determination.

The stumbling block their paper plan faced was the disinterest of the commercial radio industry itself which, at that time, was profitable and had expressed no dissatisfaction with its existing, robust FM radio transmission system. When The Radio Authority advertised the first national DAB multiplex licence in 1988, it faced the very real possibility that no radio companies would submit bids. To avoid this embarrassment, the regulator had to ‘strongarm’ Britain’s largest radio group into making the only application. GWR Group plc’s then chief executive Ralph Bernard later admitted:

“GWR was encouraged to apply for the national [digital] licence, and was under some pressure to invest in the opportunities for a national licence from the then regulator [The Radio Authority]. Had we not done it, there would be no national DAB platform now. Not only that, [the regulator] did not know what they would have done on the question of national radio stations with regard to the opportunities given by the then government to renew their national licences for a further period of time if they were to commit to going digital. But how can you [do that] if there are no opportunities to go digital because there is no national multiplex? When I put that question to The Radio Authority, I was told that the answer was: ‘We don’t know what would happen – there is no Plan B’. It was just an assumption that someone would go for [the national DAB multiplex].”

“When we were seduced into believing that this was going to be the only [national digital] licence, we realised that there would be substantial losses, but the payback would be when you have the opportunity to be the only player in the national market for DAB. When it’s The Radio Authority, an agency of government, you tend to believe what you are told. On that basis, the investment was justified and, at the time, getting it through my Board was not easy.”

Having rescued the regulator from potential embarrassment in its ill-judged pursuit of the DAB dream, Bernard naturally now held some sway over The Radio Authority and its decisions. There evidently did exist such a thing as a free lunch for its senior managers when Bernard would invite them to The Ivy restaurant in anticipation of outcomes coincidentally beneficial to his business. On two occasions at the regulator, my actions threw a spanner into this cosy relationship and I suffered consequences (see blogs here and here) from my bosses, despite me having acted in what I believed was the public’s interest. I learnt to my professional cost that I was supposed to be a ‘civil servant’ to commercial interests, not to our citizens.

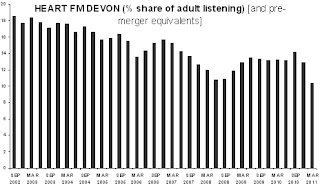

How did the story end for commercial radio? Badly. GWR Group plc’s subsequent merger with Capital Radio Group plc, both profitable public companies prior to their investment in DAB, proved a financial disaster, their DAB assets were divested for a song, an offshore investor acquired the merged business and Bernard exited the industry. This tragedy was repeated in the lower echelons of the radio business when the entire UK commercial radio industry had to be rescued by private investors. Most local radio stations that had existed since the 1970’s were replaced by national ‘brands’. Local content all but disappeared. Thousands of radio professionals lost their jobs.

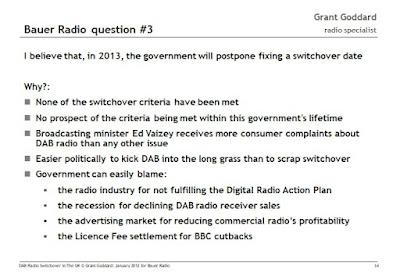

How did the story end for DAB radio? Even worse. In a presentation I was commissioned to make to the board of the second largest radio group in 2012, I predicted that the government would kick the much heralded ‘digital radio switchover’ date into the long grass. I was pooh-poohed by the company’s technologists at the meeting, but my predictions came to pass … while theirs turned to dust. Naturally, I was never invited back. British commercial radio’s enormous investment in the disastrous DAB platform impoverished the entire sector, reducing it to little more than a jukebox music service for listeners who lacked Spotify accounts.

The deluded dream finally died in 2016 when ‘Pure Digital’, the ‘great white hope’ of British designed DAB radio receivers (though manufactured in China), was sold to Austrian company ‘Aventure AB’ for £2.6m, following its £7.9m loss during 2015/6 as a result of declining sales and its “significant stock” of unsold radio inventory so old that it “needs to be assessed for risk of obsolescence.”

With the advantage of hindsight, the entire DAB debacle now seemed like a rehearsal for the similar self-harm caused by Brexit a decade later. Men in suits with little or no experience of working in the real world of commerce pursued a fever dream regardless of its practicality, oblivious to its outcomes but buoyed by their mistaken sense of superiority. Their project was to foist a uniquely ‘British’ solution on the population that would purposefully diverge the UK from the rest of the world (British DAB radios would not even function in France). Their words and documents were stuffed with misinformation and downright lies that supposedly supported their theories. Without their posh accents, they could have been mistaken for used car dealers.

Despite the wilful destruction of the commercial radio sector’s economic value, talent, creativity and public service that they had fomented, many of Britain’s DAB ‘protagonists’ went on to be lauded with industry awards, honours and lucrative jobs. For anyone who followed the Brexit disaster, it will sound like all too familiar a story.

[Originally published at https://peoplelikeyoudontworkinradio.blogspot.com/2023/10/radio-is-my-bomb-2003-dab-digital-radio.html]