A new report on the introduction of digital terrestrial radio (‘DAB radio’ in the UK) in France has recommended to the government that the launch should be delayed by two to three years. In the interim, the French media regulator CSA would be asked to establish a project to investigate the “overseas experiences” of digital radio, according to the government press release.

David Kessler, former head of state radio station France Culture, was commissioned in June 2010 by the government to produce a strategic analysis of the launch of digital radio in France. His interim report, published in November 2010 [see blog], identified the “paradox of DAB radio – it is a sufficiently attractive technology to be launched successfully, but it is insufficiently attractive to successfully allow FM broadcasts to cease.”

In the final report, published this week, Kessler said that not all the conditions had been met from an economic standpoint to permit the widespread launch of digital terrestrial radio. His report identified the significantly different challenges between digital radio switchover and digital television switchover:

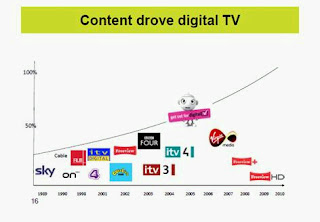

“An error in logic has probably contributed greatly to making the debate [about digital radio] opaque rather than transparent. The error came from having planned digital radio switchover with reference to digital television switchover, which started in 2005 and the success of which has been staggering and immediate, so that the changeover from analogue to digital TV will be completed throughout the land by 2012. Many parties imagined that the route to digital opened up by television would be followed by radio. But this plan was wrong for three reasons.

Firstly, the television market was dominated in 2005 by five channels (TF1, France 2, France 3, France 5/Arte and M6) that attracted 75% of television viewing. The transition to a score of free channels was obviously very attractive. However, as will be discussed later, the situation in radio is quite different – the current choice of stations is one of the richest that exists in the world, after the landscape opened up in the 80s. Even if the choice is not the same in every region, none of them – some near – are in a situation where only five major stations dominate the choice.

Second is the difference in receivers. Even if digital radio switchover had been launched simultaneously with that of television, where the evolution of televisions (flat screen, HD and now 3D) resulted in a faster replacement of equipment than anticipated, digital television was accessible without changing the set through the purchase of a single adaptor at a moderate price. Digital radio switchover requires the replacement of all receivers, and households have multiple radios and the market is sluggish. Without doubt, digital radio switchover could re-invigorate the market with a simple, inexpensive high-end (with screen) radio. At this point, no one can say how quickly take-up of replacement receivers will happen. Examples overseas – particularly Britain – demonstrate a relatively slow rate of replacement, and the different situation in countries where take-up is faster – Korea, Australia – make comparisons difficult.

The third reason is that the history of television demonstrates that it works through ‘exclusive changes’ where one technology replaces another quickly. Colour television pushed out black and white television. Digital television is about to push out analogue television. But experience shows that far from all media work this way. On the contrary, some go through ‘cumulative change’. Over a short or long period of time, different technologies co-exist and content is distributed through several technologies. As Robert Darnton noted about the book, we often forget that the printed word has long co-existed with the manuscript. From this perspective, the history of radio is the opposite of television: different transmission systems are cumulative rather than exclusive. This does not exclude the possibility that, in the long run, some transmission systems will decline and no longer be used, just as printing marginalised the manuscript. But what it means is that one cannot plan the launch of digital radio by imagining that all other transmission systems will be switched off, particularly FM. Even today, despite the success of FM, Long Wave and Medium Wave transmissions are still used because they reach a sufficient number of listeners not be switched off by broadcasters.

In fact, a careful examination of the launch of digital radio in other European countries shows that a ‘cumulative change’ scenario exists that we must anticipate in France too. Indeed, the launch of digital radio in other European countries had been presented as a quick substitute for analogue radio, even though the existing choice of analogue stations was less than in France, and the choice of digital stations seemed more attractive and content-rich than offered by analogue. Even if a proportion of listeners are quickly adopting digital radio, a greater proportion are still sticking with their traditional radios, with the possible exception of Norway, where analogue switch-off seems to be seriously considered at present. This leads to a situation in which the government initially adopts a goal of analogue switch-off but then, given the impossibility of switch-off, drops or postpones the switch-off date by several years. As the choice of existing radio stations is particularly substantial in France, it would appear that this situation is most likely to be repeated if digital radio were to be launched. Radio station owners are not mistaken. Very few want a quick switch-off of FM, and some do not want any switch-off.”

These points echo evidence on digital radio switchover in the UK that I had presented to the House of Lords Select Committee on Communications in January 2010:

“With television, there existed consumer dissatisfaction with the limited choice of content available from the four or five available analogue terrestrial channels. This was evidenced by consumer willingness to pay subscriptions for exclusive content delivered by satellite. Consumer choice has been extended greatly by the Freeview digital terrestrial channels, many of which are available free, and the required hardware is low-cost.

Ofcom research demonstrates that there is little dissatisfaction with the choice of radio content available from analogue terrestrial channels, and there is no evidence of consumer willingness to pay for exclusive radio content. Consequently, the radio industry has proven unable to offer content on DAB of sufficient appeal to persuade consumers to purchase relatively high-cost DAB hardware in anywhere near as substantial numbers as they have purchased Freeview digital television boxes.”

The Kessler document should offer significant food for thought to the British government for its unworkable plans for DAB radio switchover. Whereas Kessler correctly identified that TV and radio digital switchover are two very different undertakings, our public servants working on digital radio policy in the government and in Ofcom have long failed to understand these differences. The appointment of Ford Ennals as chief executive of Digital Radio UK in 2009, on the back of his work between 2005 and 2008 managing digital television switchover, should have been viewed as barely relevant experience to achieve successful digital radio switchover.

Have any of the people managing digital radio switchover for the UK ever actually worked in the radio industry? At DCMS? No. At Ofcom? No. At Digital Radio UK? No. If, like Kessler, they had radio sector experience, they would realise that all their speeches and presentations that repeatedly cite digital TV switchover as the precedent for radio are completely off-target.

Is there any wonder that failure of DAB public policy was inevitable?