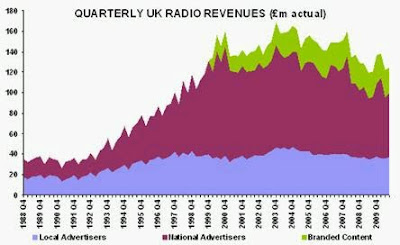

2008 had been a bad year for commercial radio revenues, down 6% year-on-year. 2009 was a worse year, when revenues fell a further 10% year-on-year. So how is 2010 shaping up? Radio Advertising Bureau data for Q3 2010 demonstrate that, although revenues are likely to be up marginally for the calendar year, they have yet to regain the substantial losses suffered during those previous two years.

Why? Because commercial radio’s falling revenues are largely the result of structural decline, something that the ‘credit crunch’ of 2008/9 merely exacerbated. Adjusted for the impact of inflation, commercial radio revenues peaked in 2000 and, by 2009, were down 32% in real terms. The single-digit improvements we might see in 2010 will claw back only a tiny part of these enormous losses.

Q3 2010 TOTAL REVENUES

· Up 3.2% year-on-year to £124.1m, but remember that Q3 2009 had been the sector’s second lowest this millennium

In May 2010, the Radio Advertising Bureau had told us that “the [commercial radio] sector has turned a corner and not only halted [revenue] decline, but moved into renewed growth …”

Industry data has yet to validate this assertion. The last two quarters produced the third and fourth lowest revenue totals of the decade, showing that the radio sector is certainly not out of the woods yet. More than anything, the industry’s revenues still seem to be bumping along the bottom. “Renewed growth” is not on the horizon yet.

Q3 2010 NATIONAL REVENUES

· Up 5.0% year-on-year to £62.8m

Q3 2010 LOCAL REVENUES

· Up 3.1% year-on-year to £36.8m

Q3 2010 BRANDED CONTENT REVENUES

· Down 1.2% year-on-year to £24.5m

The revenue data for the long term [see graph above] illustrate clearly the transformation of the commercial radio sector from a healthy growth industry in the 1990s to one that stagnated after 2000, and which has subsequently moved into decline. Whilst revenues from local advertisers have simply stalled in recent years, revenues from national advertisers seem unlikely to ever recover from substantial declines suffered since their peak in 2000. This has necessitated significant restructuring of the commercial radio sector in recent years.

For those larger commercial radio stations that depend upon national advertisers the most, the outlook continues to look bleak. Data from Nielsen estimated that advertising spend by the government’s Central Office of Information [COI] fell by 47% in 2010 year-on-year. COI expenditure has been a greater proportion of commercial radio revenues than of any other medium, making radio particularly vulnerable. In May 2010, I had predicted:

“A 50% budget cut to COI expenditure on radio would lose commercial radio £26m to £29m per annum, 6% of total sector revenues. A 50% budget cut to all public sector expenditure on radio would lose commercial radio £44m to £48m per annum, 9% of total sector revenues.”

Not only have these cuts been realised, but the Cabinet Office is continuing to pursue a plan for the BBC to carry public service messages for free, rather than pay commercial broadcasters for airtime [also predicted here in May 2010]. This could lose commercial radio a further 6% to 9% of revenues.

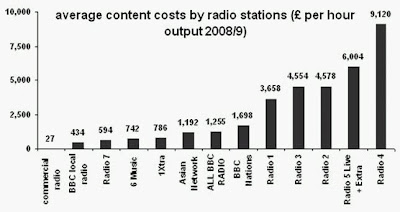

In 2009, even before these drastic cuts to government expenditure on advertising, commercial radio was attracting only 4% of total display advertising expenditure in the UK, one of the lowest proportions globally [see Ofcom report]. What is UK radio doing so wrong that Ireland, Spain and Australia achieve more than double that amount? And why was that percentage already falling before the COI cuts, demonstrating the radio medium’s comparative lack of appeal to potential advertisers?

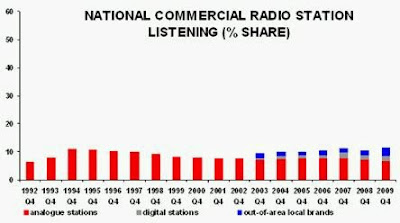

There could not be a worse time to be a commercial radio station dependent upon national advertising. Yet now is the precise time when several large commercial radio owners are busy transforming their local and regional stations into national ‘brands.’ As a response to the sector’s structural challenges, this is tantamount to cutting off your nose to spite your face. ‘Localness’ has consistently been shown to be the most important Unique Selling Point of local commercial radio, according to Ofcom research. Throw that localness out the window and all that remains is a music playlist which can be generated by any computer application.

UK commercial radio has always been good at making ‘cheap and cheerful’ local radio, but has been rubbish at making national radio that could compete with the BBC’s incredibly well resourced national networks. The recent decisions of commercial radio owners to switch from production of local radio services with a track record of success to production of ‘national’ ones that have a history of relative failure create massive risks for an industry already in decline.

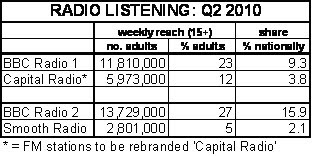

History tells its own story. The launch of the UK’s first three national commercial radio stations between 1992 and 1995 had much less of an impact on radio listening than had been anticipated. By 1997, Richard Branson had decided to sell Virgin Radio (for £115m) – it was obvious that national commercial radio was not going to be a massive moneyspinner. In 1997, Virgin Radio’s listening share had been 2.6%. Last quarter (Q3 2010), it had fallen to 1.2% (renamed Absolute Radio after another sale in 2008 for £53m), while the combined share of the three national stations was 6.8%. [source: RAJAR]

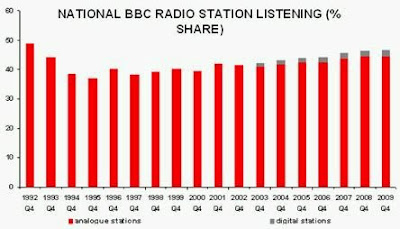

BBC national networks account for almost half of all radio listening. The only time that their share has not exhibited long-term growth was during the early 1990s, when Radio 1 self-destructed under the management of Matthew Bannister. Since that disaster, the BBC’s national networks have been successfully clawing back listening year-on-year.

The current scenario in which the owners of commercial stations that were licensed to serve local audiences have decided to subvert that purpose to take on the might of the BBC national networks is either brave, or madness, depending upon your viewpoint. What I see is a monolithic BBC that has existed continuously for nearly a century, and then I see three national commercial radio stations that have had a succession of at least three owners each during their almost twenty-year struggle to attract listeners.

National commercial radio. Just why are parts of the commercial radio industry so eager to emulate an idea that has only led to well documented failure?