Two local commercial radio stations in London – South London Radio 107.3 and Time 106.8 FM – closed forever on 3 April 2009 with little fanfare. South London Radio had launched in 1999, initially to serve the Borough of Lewisham, but its roots were in South London’s black music pirate radio stations of the 1980s. Time 106.8 had launched in 1990, serving the Thamesmead area of Southeast London, but it had been part of the cable community radio experiment of the 1970s. The closure of these two stations leaves London with only two local FM/AM radio stations based south of the River Thames (Radio Jackie in Kingston, Spectrum Radio in Battersea). Even Choice FM, launched in 1990 specifically to serve the Afro-Caribbean community in Brixton, is now relocated to Leicester Square, its latest owner having closed the station’s studios that had always been located south of the river in Borough High Street.

At first glance, the closures of South London Radio and Time might seem simply an expected outcome of the current pressures faced by many local media, particularly radio and newspapers, particularly in the UK’s largest and most crowded media marketplace. More local commercial radio stations have gone out of business in the last month than in the previous two years, with the Credit Crunch inevitably blamed for declining local advertising revenues. However, if you scratch a little deeper, the recent closures of these two stations were horribly inevitable, almost from the day they opened. What surprises me is that they managed to last this long, having struggled with a succession of owners who failed to turn them into successful businesses, and under a radio regulatory system that failed to ensure that South London’s population was offered the local radio services it had been promised.

I must declare a personal (non-financial) interest in both stations. I live within the coverage area of South London Radio and listened to it on the last occasion only days before it suddenly closed; and I had worked a one-year contract at Time’s forerunner, Radio Thamesmead, as Head of Programmes in 1986 when it was still a community cable radio station. Before they closed this month, each of these two stations was losing more than £100,000 per annum. Their accumulated losses since launch ran into millions. Yet, only five years ago, their combined market value was over £1m. How does that make sense? Their closures speak volumes about the UK commercial radio system and its inability to satisfy consumer demand for radio content via a regulated licensing system that seems to fail listeners again …. and again …. and again. Although these two legal local commercial stations are truly dead and buried, the FM airwaves of South London nevertheless remain alive with the sound of dozens of unlicensed ‘pirate’ radio stations, many of which seem to know exactly what content their audiences want and know how to give it to them.

‘Pirate radio’ had been the starting point of South London Radio, though it might have been hard to believe if you had listened to the station in its final years. Between 1986 and 1990, a pirate station named Rock 2 Rock had broadcast from the roof of the three 24-story tower blocks behind New Cross station. Its programmes of soul, reggae and community information attracted a loyal following in South London and, although the station might not have been as well known as competitors such as LWR, Horizon or Solar, its signal reached across the capital, and its DJ roster exhibited a love of the music they played at a time when legal radio continued to shun black music almost totally. “Most of the people who were involved in [Rock 2 Rock] lived or worked in the Lewisham Borough,” DJ Inspector Scratch-It told me in 1992. “I don’t even really know what the secret [of our success] was. It was just something [indefinable].”

In the late 1980s, local resident Stella Headley had walked into her local reggae record shop, Sound City in Deptford, and asked if she could present a show on pirate radio. Despite having no radio experience, but armed with a passion for jazz music, Stella was offered a show on Rock 2 Rock where she called herself Lady X. The station quickly became ubiquitous in the area. “The way that we had broadcast was so down-to-earth and friendly,” Stella recalled when I interviewed her in 1992 [Radio Scan, City Limits #562, 16 July 1992]. “It was something that everyone could relate to.”

In late 1990, the government of the day introduced draconian laws that made it a criminal offence to be involved in the promotion or broadcast of pirate radio, with the possibility of a prison sentence even just for wearing a pirate station T-shirt or having a pirate radio sticker on your car. Rock 2 Rock, along with dozens of other pirate stations of the time, decided voluntarily to close down. “It was pressure,” explained Inspector Scratch-It, “realising that things could really start getting bad if we did get caught”. Some of the station’s twenty DJs moved on to work at new, legal ‘incremental’ stations that had just been licensed to satisfy previously unfilled gaps in the radio market – Mistri, one of the most popular club DJs of the era, joined short-lived WNK in North London; and I recruited Angie Dee to the launch of the legalised London ex-pirate KISS FM. Ten others, including Stella, started a new venture called First Love Radio which went on to campaign for Southeast London to be given its own commercial radio station.

A £5,000 grant from South Thames TEC enabled the group to organise formal radio training for local residents. A temporary, one-month FM licence (under the Radio Authority’s Restricted Service Licence scheme) showcased to residents of the Borough of Lewisham the content which the station wanted to be able to broadcast legally. Inspector Scratch-It explained: “We’ll be doing things we would have liked to have done when we were a pirate. Now we can plan ahead and use more people from the community, without fear of being arrested. I know how hard it was to maintain the [Rock 2 Rock] station. Every time there was a knock on the door, your heart was going thump, thump, thump”.

First Love Radio completed several, successful one-month local broadcasts, and by 1997 the Radio Authority was sufficiently impressed to advertise a small-scale commercial radio licence for Southeast London. To be sure of winning the licence, Stella involved commercial radio group UKRD as a partner and majority shareholder who, in turn, recruited community radio consultant Des Shepherd to write the licence application. In January 1998, the Radio Authority announced that it had selected First Love Radio as the winner from amongst eight applicants. The Authority noted proudly that “this is the 22nd ILR [Independent Local Radio] service to be awarded covering Greater London or parts of the capital”.

However, the station’s winning licence application promised, somewhat surprisingly, that its output would “represent the diverse tastes and interests of its target audience by providing a dynamic music mix from the 60s through to the 90s with high quality local news and information for the Borough of Lewisham”. Gone was any specific commitment to serving the substantial Afro-Caribbean community within the Borough. Gone was any specific commitment to playing soul and reggae music. It seemed that, while the Radio Authority was busy congratulating itself that it had licensed its 22nd station in London, it had condemned First Love Radio to become simply another tiny little station in the UK’s biggest radio market that would be playing the same pop music hits that everyone else was. The eventual fate of First Love was sealed there and then.

Whereas Rock 2 Rock had embodied a quite Unique Selling Point in its music format, First Love Radio was destined to be ‘all things to all people’. As one writer noted of its music policy, “this is perhaps as diverse as a radio station can get”. Owner UKRD was not really interested in the business of operating a black music station for Lewisham. UKRD was in the business of collecting local radio licences. A London licence held intrinsic value, whatever you did with it, and the cost of a licence application was probably no more than the low tens of thousands of pounds, while the scarcity value of any London licence made it worth millions. UKRD was an investment machine, turning paper licence applications into valuable licences, rather than a turnaround specialist turning poorly performing radio stations into success stories.

First Love Radio launched as a full-time station in 1999 but achieved dismal ratings so, in 2000, UKRD sold it to Fusion Radio Holdings, a new company established by radio salesman Nigel Reeve to acquire local radio licences. Stella Headley tendered her resignation from the Board little more than a year after her station had launched, abruptly bringing to an end her decade of hard work to secure a local station for Lewisham. The ideals of First Love Radio were already dead. Veteran radio presenter Roger Day was appointed Programme Controller of the station, whose name was quickly changed to Fusion 107.3. Reeve said: “We are delighted to have acquired two radio stations [Lewisham and Oxford] with huge growth potential. Plans are in place to build revenue and increase audience figures….”

In 2001, Fusion Radio Holdings and its three stations (Lewisham, Thamesmead and Oxford) were acquired in a deal worth £4.1m by another corporate collector of local licences, the Milestone Radio Company, which was run by former radio presenter Andy Craig. Media Business reported that the deal “puts an end to industry speculation concerning the demise of Fusion Radio [Holdings], following the move from its West End location to Lewisham”.

In 2002, Fusion 107.3 was instructed by the Advertising Standards Authority to withdraw a poster campaign that featured “a photograph of the naked torso of a woman” whose “nipples were airbrushed out and radio dials were positioned at the bottom right-hand side of her breasts”. Complainants had objected that the poster was “sexist and demeaning to women”, though the station’s owner argued that “the poster was designed as a high-impact campaign to attract new listeners” and that the model’s “radio dials [were] pointing south east to emphasize the geographical range of their broadcast”.

Three owners in three years were still failing to make First Love Radio/Fusion 107.3 a success. In 2003, Milestone raised £8m from an AIM share listing, despite admitting that it had “limited revenues to date and … accumulated net losses”. The pre-AIM company had suffered pre-taxes losses of £5m in 2001 and £4m in 2002, on turnover of £0.6m and £1.7m respectively. By 2003, Fusion 107.3 was still only attracting 6,000 listeners per week in a local market of 322,000 adults. The station was already losing more than £300,000 per annum, so Milestone put it up for sale.

In February 2004, after a year on the market, Sunrise Radio acquired both the Lewisham and Thamesmead stations for £1.2m. Sunrise (coincidentally an ex-pirate station) had run a successful, legal Asian radio station in London since 1989 and wanted to diversify into mainstream radio formats. In January 2004, former Radio Authority finance director Neil Romain had been recruited to head new Sunrise subsidiary London Media Company which would manage these stations.

Once again, the station’s new owner appeared to miss the opportunity to imbue the station with a Unique Selling Point to differentiate it from its many competitors in the London market. The station was renamed South London Radio and its web site was branded “All Time Favourites”, a radio format similar to that already offered in London by Heart FM, Magic FM, Gold London and Smooth Radio, amongst others. As a result, in 2006, the station was given a ‘Yellow Card’ sanction by Ofcom because it was found to be failing its mandated music format. Ofcom said the station “should have a distinct musical sound” whereas “over 50% of the daytime output fell within the Hits/Pop genre”.

As well as the change in station name, the new owner asked Ofcom’s approval in 2006 to temporarily move the station’s studio out of its Lewisham service area to share premises with co-owned Time 106.8 in Thamesmead. There was a subsequent period when the station operated from a business centre in Croydon. At the same time, it appears that improvements to the station’s transmitter were granted that enabled the station to be heard across a wider area that included parts of the Croydon and Bexley boroughs for the first time, extending the potential audience to 645,000 adults. Eventually, the station returned to co-location in Thamesmead.

During this whole period, the station’s music policy continued to be a bizarre mish-mash of current hits and the oddest selection of ‘black music’ that seemed scheduled purely to satisfy Ofcom’s prescribed Format requirement to appeal to “listeners with a preference for soul/Motown, R’n’B, reggae and dance hits”. So the daytime output might make transitions straight from Nat King Cole to Lily Allen, or from Dionne Warwick to the Pussycat Dolls. Whilst I personally like eclectic mixes of music styles, South London Radio ended up sounding particularly schizophrenic. Five years under the same owner should have provided plenty of time to make the station at least sound consistent and instil it with a sense of purpose. Neither Romain, without prior radio management experience, nor Sunrise, without experience in black music formats, achieved a successful turnaround of the Lewisham station.

In 2008, a notice appeared on the consumer-facing homepages of the Lewisham and Thamesmead stations, informing interested parties that both were up for sale and inviting bids. Sunrise Radio’s Avtar Lit explained: “They are good local businesses but they do not fit in with our portfolio. Traditionally these stations have always made losses but we have reduced those losses dramatically. The days of large companies running a number of local radio stations are gone, simply because the decision-making process is too far removed.” There was at least one bid lodged for South London Radio, but the offer deadline passed and no transactions were reported. Precisely what happened next is open to interpretation…………

The official web site of South London Radio includes a message which explains (in part):

“Both stations were sold on 22 February [2009] to an individual who, after seven days of ownership, informed staff that he could not afford to fund the stations and would need to sell one station to fund the other. At this point, staff had already not been paid for the month of February. Since the announcement, staff have been working at the station free of charge in the hopes a new buyer would be found. After a lot of work, a potential buyer was found who was very keen to acquire the stations and take them forward. Several obstacles were put into their way which saw the sale of both stations put on hold……”

The Radio Today web site initially reported on 4 April 2009 that both stations had closed because they had been “up for sale but no suitable buyer was found”, though its storyline was later amended to match the explanation on the stations’ web sites.

According to the Company Register, on 22 February 2009, Sunrise Radio’s Avtar Lit, London Media Company’s Neil Romain and Company Secretary Sonia Daggar resigned as directors of South London Radio. On the same date, Arvind Kumar Audit was appointed sole director of South London Radio, and a loan to the value of £1,029,704.61 was made from Sunrise Radio to South London Radio which gave Sunrise first call on the station’s assets. Staff at the stations have suggested that a relative of Lit was brought in to manage the Thamesmead operation, though this allegation remains unsubstantiated. For the brief period the two stations remained on-air, Audit was listed in their Public Files as Station Manager. However, Ofcom did not publish a Change of Control review for these transactions.

In legal terms, it would appear that Sunrise Radio/London Media Company sold the stations weeks before they closed, though why someone would decide to purchase a loss-making station that had a £1m loan outstanding to its previous owner remains a mystery. Nevertheless, the circumstances make it impossible to suggest that Sunrise Radio/London Media Company themselves closed these stations (as Radio Today had initially stated) because the stations were not officially under their control when the plugs were pulled. This subtlety might hold some importance to Sunrise or Ofcom, but it remains wholly irrelevant to the local people of South London who no longer have a local commercial radio station, whatever did or did not happen.

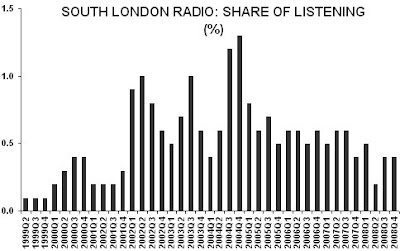

Admittedly, listeners to South London Radio were few in number as a result of the station’s consistent failure to connect with an audience. Its market share only surpassed 1% during two quarters of its decade on-air, though most of the time it registered less than 0.5%. In the station’s launch year, its listeners numbered less than 1,000 adults per week although, by the time it closed, that number had risen to 19,000 within its significantly enlarged coverage area. These numbers would still prove too low to adequately finance a local radio business in London. The station had never stood a chance from the time that UKRD saddled it with a pop music format in its licence application.

South London Radio never made an operating profit from airtime sales, not even in its earliest days. The only period of positive cashflow occurred in 2004 and 2005 when £1.7m compensation was received from its landlord when the station was forced to vacate its premises, presumably before its tenancy had expired. Ironically, this windfall was twice the size of the advertising revenues received by the station during its entire lifetime. Although, in recent years, its owner had managed to substantially reduce the station’s overheads, revenues had fallen to as little as £1,000 per week by then. There are pirate stations in South London that earn more money than that.

South London Radio never made an operating profit from airtime sales, not even in its earliest days. The only period of positive cashflow occurred in 2004 and 2005 when £1.7m compensation was received from its landlord when the station was forced to vacate its premises, presumably before its tenancy had expired. Ironically, this windfall was twice the size of the advertising revenues received by the station during its entire lifetime. Although, in recent years, its owner had managed to substantially reduce the station’s overheads, revenues had fallen to as little as £1,000 per week by then. There are pirate stations in South London that earn more money than that.

South London Radio’s final owner (or ‘penultimate’ owner legally) seemed to know where the blame lied for the station’s failure. In one set of Annual Accounts, its directors said:

“Despite significant investment by the management, the station has continued to perform below expectations. The impact of illegal broadcasters compromising the transmissions of this station is the main reason for the poor financial performance. The Directors are continuing to lobby the regulators in an attempt to find a solution”.

It was this lobbying by Sunrise Radio (a former pirate) of Ofcom which led to the transmitter power increase that significantly extended the station’s coverage area. Its owner then increased the survey area for the station’s RAJAR audience ratings from 304,000 to 1,472,000 adults, but the station’s weekly reach stubbornly remained at around 1%. Perhaps the owner thought that a station which claimed to reach 1.5m people across South London was more likely to find a buyer than a station that served only the relatively poor Borough of Lewisham. Whatever, South London Radio eventually closed with accumulated losses estimated at almost £2m, a figure that would have been twice the size, had it not been for the windfall settlement the station received from its previous landlord.

So it’s all over now, a sad end to Stella Headley’s dreams and also the death of what was supposed to be my local radio station. Hopefully, some lessons can be learned from this sorry tale. Some of these ‘lessons’ seem so glaringly obvious that it is almost embarrassing to point them out, but the 36-year history of commercial radio in the UK is so littered with repeated failures that it is worth spelling out some of the things that evidently went wrong. First Love Radio is just one of many local stations that have failed with both audiences and advertisers because of structural and procedural faults within the UK’s commercial radio system.

POSSIBLE LESSONS

1. CAN A DESIGNATED LOCAL MARKET SUPPORT AN ADVERTISING-FUNDED COMMERCIAL RADIO STATION?

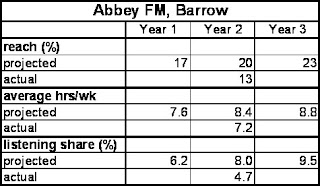

Before advertising a new licence for a specific geographical area, the radio regulator did not evaluate whether there were sufficient local advertising revenues to support a commercial radio station for that area. This was true of Lewisham when the Radio Authority advertised this licence in 1997. A decade later, it was probably just as true of Ofcom when it awarded new licences for a talk station in Edinburgh (now closed), a rock music station in Plymouth (never opened), a station serving a population of 65,000 adults in Barrow (now closed), or a station serving a population of 30,000 adults in Northallerton (now annexed). Whether it was the Radio Authority or Ofcom, the regulator was issuing ‘licences to fail’ that never stood a chance of being successful, standalone businesses.

2. LOCAL RADIO GROUPS ARE FODDER FOR THE AMBITIONS OF COMMERCIAL RADIO GROUPS

First Love Radio is not the first local radio group to have organised short-term broadcasts in their area, organised training, raised public funds and raised local awareness of it campaign for a local station. Then, when it comes to writing the licence application, many such groups jump into bed with a commercial radio group that has no understanding of the group’s aims, the proposed station’s format, or the local marketplace. The radio group is interested in the licence, and the local group believe that such an alliance will ensure that licence will be won. An outside ‘consultant’ is brought in to write an application that is likely to win the licence, rather than an application that tells the truth.

3. NEW LOCAL COMMERCIAL RADIO LICENCES ARE AWARDED TO APPLICANTS THAT ALREADY HAVE COMMERCIAL RADIO LICENCES

To those that already have shall be given …. again and again and again. How many of Ofcom’s 39 new local radio licences between 2004 and today were awarded to applicants that did not already own a radio station? Ony one. It’s a regulatory gravy train of licence awards, which works great for those lucky few who already have a seat on the train. For those genuinely local radio groups who simply have a desire to run a radio station in their local area, the message is – you don’t stand a chance of winning a licence on your own.

4. MOST LOCAL RADIO GROUPS’ EXPERTISE IS IN COLLECTING LICENCES, NOT IN TURNING AROUND LOCAL RADIO STATIONS

As noted previously, the cost of making a licence application is usually a five-figure amount, whereas the balance sheet value of a radio licence is either a six- or seven-figure sum. The ‘business’ skill of most local radio groups has been based upon turning paper radio licence applications into valuable intangible assets to add to their balance sheets. Sadly, it has not been based upon launching successful local radio stations (‘successful’ meaning profitable), or upon turning around unsuccessful stations.

5. RADIO LICENCE APPLICATIONS ARE GENERALLY NOT GROUNDED IN REALITY

The promises made in most licence applications are mostly over-optimistic ‘waffle’. The lavish programming, the potential profitability, the audience targets – most of these are written purely to fit what the applicant radio group thinks the regulator wants to hear. Almost every licence applicant promises that its business will break-even within three years, despite evidence that there are very, very few newly-launched stations that have achieved such a performance in the last 20 years. Rule Number One of licence applications – never let the facts get in the way of a good story. As a result, the performance of most start-up stations is more than dismal. The graph below shows the percentage plus/minus achieved in hours listened versus the forecast hours listened in the station’s licence application for new local stations licensed during the last five years. Only four stations managed to beat their targets. (The crosses represent stations that have closed.)

Because of the untruthfulness of most licence applications, if you were to submit a more realistic assessment of your business plan within a licence application, it would look very gloomy compared to your competitors. Do you get any credit for being realistic (i.e. honest)? No, you are unlikely to be awarded the licence.

Because of the untruthfulness of most licence applications, if you were to submit a more realistic assessment of your business plan within a licence application, it would look very gloomy compared to your competitors. Do you get any credit for being realistic (i.e. honest)? No, you are unlikely to be awarded the licence.

6. THE REGULATOR DOES NOT ‘POST MORTEM’ ITS LICENSING DECISIONS

When the Independent Broadcasting Authority licensed the ‘incremental’ stations, did it publish a report to show why so many of them went out of business within their first year? No, it didn’t. When the Radio Authority licensed the ‘regional’ stations, did it publish a report to show why these stations had no impact on enabling commercial radio to be more competitive for audiences against the BBC? No, it didn’t (I did my own research). Now that Ofcom has licensed so many new local stations, has it published research to show why so many are already proving unviable and whether awarding new licences to existing licensees had proven the appropriate regulatory policy? No, it hasn’t (see research in John Myers report). In all these cases, there seems to have been no attempt to learn from past experience, and thus no attempt to assess the positives and negatives of regulatory policy. To an observer, the attitude might look remarkably like ‘OK, that didn’t really work, so let’s try something different now’.

7. A LOCAL RADIO LICENCE ONLY ACQUIRES INTRINSIC VALUE IF YOU DO SOMETHING CONSTRUCTIVE WITH IT

Local radio groups can play the game of putting inflated values for their local radio licences on their balance sheets. But unless you can actually find someone who is willing to pay that inflated price, your licence in reality is worth nothing at all. After an era of crazy acquisition prices during the 1990s, we are now in a period where there have never been so many station sellers, but almost no buyers for the majority of small local radio licences. The ‘house of cards’ that was carefully constructed over the last two decades is already falling down. The radio licence gravy train bears some similarities to the vulnerability of a Ponzi scheme. Now that Ofcom is no longer offering new local radio licences, the ability of radio groups to continue to improve their balance sheet valuations through more licence wins has ended abruptly. As a result, their existing stations are now revealed to be worth a lot on paper, but worth almost nothing in reality because there are no buyers (i.e. other local radio groups with similarly over-inflated balance sheets). The underlying fallacy of the licence award system is now revealed.

8. THE TRACK RECORD OF MOST SMALL LOCAL RADIO GROUPS IS NOT GOOD

There is simply no money to be made from owning a number of small local radio licences, unless you have proven turnaround skills. Plenty of companies have raised millions of shareholder funds, promising to return them a profit from a cluster of loss-making local radio stations. The profits never arrived. Laser Broadcasting went bust. Forever Broadcasting went bust. The Wireless Group sold out. Golden Rose sold out. Milestone sold out. The Local Radio Company is on its knees financially. You might think that this history of failures would be sufficient warning to future investors that adding X number of loss-making local commercial radio stations to Y number of loss-making local commercial radio stations does not equal profits. Apparently not.

9. THERE IS A WIDENING ‘REALITY GAP’ BETWEEN WHAT THE REGULATOR IS REGULATING ON PAPER, AND WHAT IS ACTUALLY HAPPENING IN LOCAL RADIO MARKETS

On paper, each of the UK’s 300 commercial radio stations has a distinct ‘Format’ it has to follow, theoretically offering it a unique position in its local market. In this highly regulated system, Ofcom is supposedly ensuring that a diverse range of consumer demands for radio content are being simultaneously satisfied in each market. Even a casual radio listener realises that this system is a fiction. London has a large number of local commercial stations, and many of them sound remarkably similar, despite on paper them being meant to be different from their competitors. If South London Radio had offered different content and satisfied local demand for content, it might have thrived. Despite its Yellow Card sanction, Ofcom failed to ensure that South London Radio was satisfying the demand in South London for a local, black music station.

10. THE CLOSURE OF A LOCAL STATION IS THE FAULT OF BOTH ITS OWNER AND THE REGULATOR

It is very easy for the regulator to step back and say that the commercial failure of a specific local radio station is not its responsibility because it does not interfere in the business operations of its licensees. Frankly, this is a cop-out. Eight applicants applied for the Lewisham licence awarded to South London Radio. Seven were never even given the opportunity by the regulator to create a successful local radio station. Our public servants in the regulator were supposed to use their knowledge and expertise to select the applicant that was most likely to ‘win’. Ofcom even has a web page where it explains why it selected one applicant above the others for each licence. If the regulator’s choice was misguided, mistaken or ill-informed, it should have to explain what went wrong (a bit like this blog entry?). Surely, the regulator owes such an explanation to the listeners the station was supposed to serve and also to the unsuccessful licence applicants who, as a result of the regulator’s judgement, have no ‘second chance’ to put their own proposals for a radio station into action.

11. RADIO STATION OWNERS ARE NOT REQUIRED TO SELL STATIONS, RATHER THAN CLOSE THEM

I have heard several radio group executives say that they would rather close down one of their loss-making stations than sell it for £1. There are several issues at play here. Firstly, closing a company creates an opportunity to move some liabilities from elsewhere in the group before the station is made insolvent. Secondly, radio owners don’t want the embarrassment of someone else successfully turning around a station that they had not managed to make profitable over several years. Thirdly, if an owner paid £1m for a station, it is embarrassing for the CEO to have to tell their Board that it had to be sold for £1. The end result, as in South London, is that listeners no longer have a local radio station at all, rather than the baton being passed on to someone else to try and make the business work. Again, it is the listeners and the unsuccessful licence applicants who lose out.

12. THE SCARCITY OF LOCAL RADIO LICENCES HAS TURNED THEM INTO TROPHY ASSETS

If you want to start a local newspaper, you simply start it. You don’t need a licence. If you want to start a local radio station, you cannot. You have to wait for Ofcom to decide to offer a licence for your area, then you have to apply for it, and then you have to win it. In this case, Ofcom is unlikely to offer another South London FM licence to replace South London Radio. That opportunity came and went in 1997. As a result, there are far too many owners coveting local radio licences because of their scarcity, hoping that at some point in the future a ‘white knight’ will still ride over the horizon and pay an outrageous sum for it, regardless of the fact it is losing money every year and has accumulated losses of millions. After the Communications Bill opened up UK radio ownership to non-European Union stakeholders, there were several radio owners who were waiting for a global media company such as Clear Channel to ride into town and offer them a small fortune for their failing businesses. It never happened, and sadly there was no ‘Plan B’.

13. THE LACK OF CREATIVITY IN COMMERCIAL RADIO

There is a terrible lack of creativity within the commercial radio sector that is severely holding back its ability to compete with the BBC, let alone to compete with the flood of audio content available via the internet. It is far easier for radio companies to simply do either the type of content that they have always done and/or the content that everybody else is doing, rather than to be innovative or creative. In the case of South London Radio, I understand that its owner was approached last year by at least one radio consultant (not me) with a plan to resuscitate the station by returning it to its original roots as a black music outlet. That proposal was rejected.

14. THE REGULATOR PRETENDS TO ADOPT A ‘LIGHT TOUCH’ APPROACH TO COMMERCIAL RADIO REGULATION

If the regulation of commercial radio in the UK were genuinely ‘light touch’, then it would be appropriate that the regulator makes no attempt to intervene in the failure of individual stations. However, the system of radio regulation (even under Ofcom) intervenes heavily in almost every aspect of the commercial radio landscape, down to such detail as whether a particular station can play a specific song within its output. In such a highly regulated market where Ofcom exercises such a high degree of control, the regulator should surely have a responsibility to the citizen/consumer to ensure that the relatively small number of stations it selects to license (compared to the total number of applicants) continue to exist in some shape or form. It is not consistent to intervene at every moment of a station’s existence, except when it is finally threatened with closure as a direct/indirect result of the regulatory system.

15. NO CONSULTATION WITH LOCAL STAKEHOLDERS

Ofcom makes a big noise about its consultation system and its willingness to listen to the opinions of a wide range of stakeholders. However, when a station is threatened with closure, has the regulator ever consulted with local advertisers to consider the impact on them, with local community organisations who used the station to inform the local population of their activities, or with the local population itself? Would it not be useful to talk to Stella Headley now and canvas her opinion of what precisely had gone wrong with First Love Radio since 1990 (I tried to locate her for this blog entry but failed)?

The irony of South London Radio’s closure is that, over a ten-year period, things have already gone full circle. South London Radio was born from the experiences of pirate radio in the Borough of Lewisham, and now it is the pirate stations once again that are carrying the torch for those of us living in this area of South London. There is presently a great pirate station in Lewisham that sounds like the natural successor to1980s pirate Rock 2 Rock, playing reggae and soul music for ‘big people’. I can listen to this station on FM or via the internet (telling you its name would break the law) and it entertains me in a way that the latter day South London Radio never achieved. I used to listen to Rock 2 Rock in the 1980s, and now I am listening to its successor.

First Love Radio R.I.P.

It appears that our highly regulated and interventionist commercial radio system has:

* completely failed the people who originally put the idea together for First Love Radio

* completely wasted the public money invested in training people from the local community in Lewisham to make radio programmes

* has completely failed the population of Lewisham and beyond who should have their own radio service.

These failures in public policy will continue to have to be filled (though not fully because of the threat to those involved of criminal prosecution) by the efforts of unlicensed radio stations in Lewisham. A document published by the publicly funded Creative Lewisham Agency lamented that “television and radio is a very small Creative Industries sub-sector” in the north of the Borough ….. but then it noted that pirate radio is “a contributor to the Creative economy” and “is certainly vital for networking and showcasing”. When you find public bodies extolling the citizen value of pirate radio, you know for sure that something in our radio licensing system has gone very badly wrong.

As Inspector Scratch-It recalled of his Rock 2 Rock days: “We even had links with the police and [Lewisham] Council. They used to send us information that was relevant to read out, even though we were a pirate.” Twenty years on, it is still pirate radio filling that gap.

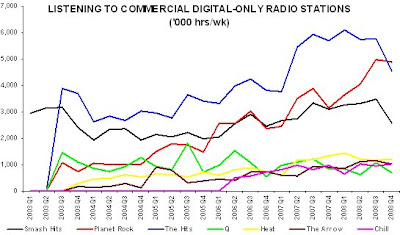

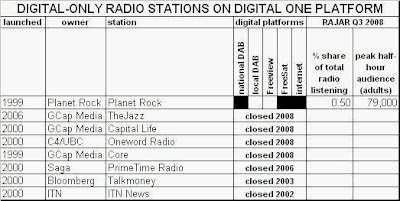

It hardly inspires confidence in the Digital One DAB platform that Global Radio’s predecessor, GCap Media, closed three of its own digital-only stations carried on its platform last year, and sold Planet Rock to an entrepreneur with no other radio interests. Neither is it a good advertisement for Digital One that its

It hardly inspires confidence in the Digital One DAB platform that Global Radio’s predecessor, GCap Media, closed three of its own digital-only stations carried on its platform last year, and sold Planet Rock to an entrepreneur with no other radio interests. Neither is it a good advertisement for Digital One that its