House of Commons Culture, Media & Sport Committee

“The future for local and regional media”

27 October 2009 in the Thatcher Room, Portcullis House

Andrew Harrison, chief executive, RadioCentre

Travis Baxter, managing director, Bauer Radio

Steve Fountain, head of radio, KM Group

[excerpts]

Mr Tom Watson: Can I ask you about Digital Britain and the Digital Britain Report? Do you think the report gave a good way forward for the commercial sector to journey out of its current troubles?

Mr Baxter: Perhaps I could ask Andrew to give an overview on that and then maybe we can give our respective views?

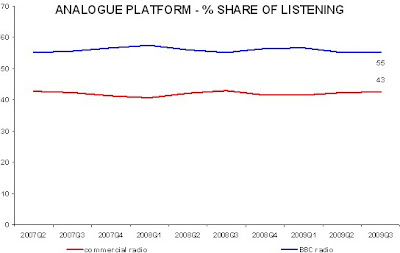

Mr Harrison: To give an overview, I think the short answer to that is “yes”. One of the fundamental issues the sector faces right now is the appalling cost of dual transmission. Ultimately, right now, this is a small sector and very many of our stations are simultaneously paying for the cost of analogue and digital transmission. That clearly does not make any financial sense. What we advocated for in Digital Britain was a pathway for all stations to end up with a very clear plan of what is the single transmission platform for them. That led, as I said in my opening remarks, to three very complementary tiers of the commercial radio offer. The first tier is a strong national offer on digital to compete with the BBC, and that is critical for the sector because the truth is that the FM spectrum is full. I am sure all of you will know from some of the other conversations we have had before that the BBC dominates the gift of analogue spectrum. It has four national FM stations; we only have one with Classic FM. For the sector to compete and capture its share of national advertising revenue, the ability to have a national digital platform I think is critical. As we then had the conversations with Digital Britain, I think it became very clear to all of us that you cannot just migrate national stations to digital and leave all of the large metropolitan local stations, like City in Liverpool for example or Metro in Newcastle, all the BBC’s local stations, as analogue only. The listeners to those stations will want the functionality, experience and benefits that come with digital. It is then very important that we have a second tier of the large local and regional stations which also migrate to digital. Critically, however, that nevertheless leaves an important third tier, which are the smaller or the rural stations for which either DAB coverage is currently not present – there is just not the transmitter build-out in some of the rural areas – or for which it is likely to be prohibitively expensive going forward. That sector equally needs clarity and that sector being able to stay on FM alongside community radio we feel gives a very balanced ecology where the sector has the most opportunity to compete and the lowest cost base because each station can ultimately choose whether it is on one transmission methodology, i.e. digital, or another, analogue. At the moment, we are in limbo where stations are paying for both but the profitability of the sector is fragile and there is not a plan. So we absolutely welcome the beginnings of that plan, which we recognise is the start of what is going to be a long and difficult journey as stations migrate and decide if their future is on digital only or their future is on analogue. The quicker we can move the industry there, clearly the better for the fragile economics of the sector.

Mr Baxter: Perhaps I can encapsulate some of the things we sent in to the Carter Review. Our business view generally is that the future is digital. There is hardly the need for me to make that clear to you. Our view has been for the last ten years that we will look at all platforms as we develop our business. We have successful radio stations, primarily operating for example off the audio channels on the Freeview digital television system. However, within that we think it is of real value for radio to have a bespoke platform and the one that is available to us that is a bespoke broadcast platform is DAB. It has, however, taken 12 to 13 years of very slow development for that platform to get to its current state. Therefore, our proposition to Carter’s Review was: let us get on this horse or get off it. We think we should get on it and put every possible energy we can over the next view years into getting consensus, direction and pace into the whole process of take-up, like there has not been during the last 12 years. If that can be achieved, it will produce a new resonance for commercial radio as a whole, indeed for the whole of radio. It will help position radio more effectively in the fragmenting media landscape we all have to deal with and give us an opportunity, as Andrew said, of clarifying our investment levels around platforms where currently we are having to pay for two when, in a future where either one is successful, we would only have to pay for one, thereby allowing resource to be put into developing content and other things around our business.

Mr Fountain: KM Group does have a digital platform. It is currently costing us over £100,000 a year and we get absolutely nothing back from it. I think the company at the time, six years ago, took the view that they wanted to be a part of the future. Circumstances since have not really helped them to be able to develop that particular medium. I think we too take the view that we would want to be part of a digital platform going forward, but there are a number of issues that would need to be overcome, not least of all the cost of entry and also in our particular case our DAB coverage and the coverage of our FM stations is not mirrored. We have better coverage right now on our FM platforms than we do on our one single DAB coverage. The problem around the coast, if you take that from Medway right the way round perhaps as far down as Rye, around the Kent coast and just touching into Sussex, is such that DAB does not actually reach into large parts of that coastal area.

Mr Watson: Would DAB+?

Mr Fountain: I could not answer that because I do not actually know.

Mr Harrison: No, there is no difference in terms of the coverage for DAB or DAB+. DAB+ is just a different method of compressing the signal so you can actually get more signal down the pipe, if you like; you tend to get more stations, but it does not actually affect the coverage.

Mr Fountain: You can see that in order for us to extend the coverage of DAB, there is clearly a cost involved, and there is also a conversation to be had between Ofcom and the French communication authorities as well.

Mr Watson: Presumably you are all relatively happy with what is quite a demanding timetable outlined in Digital Britain if your view is that we should just get on with it and do it?

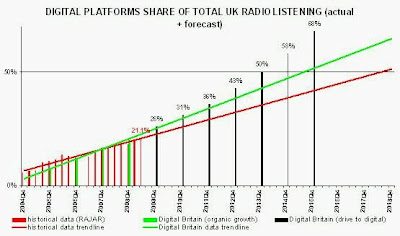

Mr Harrison: I think you have expressed it exactly right. The timetable is demanding. I think it is set deliberately as being demanding. Digital Britain does not set a date for switchover. What it sets are two criteria that it says are axiomatic to be hit before switchover can be contemplated: one on listener levels and one on coverage, both of which we support. The aspiration in Digital Britain is to try and hit those two gates, if you like, by the end of 2013. On what Travis was saying earlier on, we think that is absolutely right, that the industry now works terrifically hard together, alongside the BBC and alongside the Government and the regulator to do our very best to hit those criteria. Once we then hit the criteria, the Digital Britain report identifies that it will probably take a couple of years from the criteria being hit before we could actually contemplate switchover. That is aggressive but we think it is appropriately aggressive against the context of an industry that is clearly struggling financially now, and the vast majority of my members are highlighting the cost of dual transmission as the single biggest cost issue that they face and self-evidently one that could be eliminated the quicker we can get to a decision one way or the other.

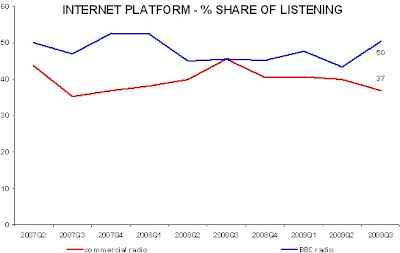

Mr Watson: May I ask you a bit of a left field question? You are quite confident that we should move to digital radio quite quickly. How confident are you that consumers will want to make that journey and that they will not migrate to internet, radio or choose to listen to live streaming sites like Spotify?

Mr Harrison: There are two different points there. We are quite confident, as you say, about the movement to digital, but purely because what the Digital Britain Report sets up are consumer-led criteria to drive that change. The criteria are absolutely that we will not move until coverage is built out to match FM. It would be absolutely suicidal for the industry to switch people off who currently listen and enjoy radio services, so it is axiomatic that we have to build coverage out. Secondly, the criterion is that listenership to digital has to be that the majority of all listening has to be to digital before you would contemplate switchover. We are not going to rush into this without being led by the consumer. What we are trying to do, as Travis said earlier, is inject some pace, momentum and energy into the process. If we wait for the natural replacement of sets and the natural progression of DAB – it has taken a long time to get to the listener levels we have right now, we still have all of the BBC’s services for example available on analogue – it is going to be very difficult to kick start the progression. We are very comfortable but we are comfortable because it is led by the consumer. The second part of your question is: are we worried about competing services? We are absolutely. I think there is a whole generation of new entrants into the market – Spotify, Last.fm, Pandora – available on-line, all of which are unregulated and against which we are competing for listeners and for advertising revenue. When you have a small, heavily regulated, constrained local radio sector competing with an unregulated world-wide series of music offerings, that is one of the challenges we have to face. We are, however, absolutely committed to the importance of a broadcast transmission methodology for digital. That is not to say that the internet will not be an important complement to that but our business model is based on a broadcast signal of one signal to a wider audience. There is very little evidence so far that on-line music offerings are in themselves profitable business models. For UK citizens and consumers, for our listeners, we think it is absolutely critical that radio remains free at the point of delivery. That has been one of its great strengths ever since the BBC was founded in the 1920s. Of course at the moment, although as I heard this morning the cost of broadband is potentially down to £6 a month, nevertheless, to access any internet-delivered service, you have to pay an ISP connection. That may change but I suspect we are a long way away from that.

[edit]

Mr Watson: Do you think the car industry is sufficiently prepared for the digital revolution?

Mr Baxter: I think we have had some very encouraging conversations with the motor industry over the last six months. The response to Carter’s work during the beginning of this year has helped galvanise interest in that area quite significantly, so I think there is a very different aura around those discussions than there was 12 months ago.

Mr John Whittingdale, Chairman: Just on the cost of the digital upgrade, what is your best estimate of how much it is going to cost?

Mr Harrison: I was on the working party, the Digital Radio Working Group, that was the forerunner for Digital Britain. That working group identified the cost of build-out, the one-off capital cost, as between £100 million and £150 million. That is quite a spread. The reason for the spread ultimately depends on what degree of coverage build-out you get to from equalling FM to universality and at what signal strength. Of course, you get real diminishing returns as you go to the very rural areas. That is the reason for the spread. There has been a lot of debate about that number. In reality, the way we have tended to look at it is that if you take that spread of £100-£150 million over the 12 year period of a licence, which is typically when a radio station is licensed or a multiplex is licensed, and if you said for round figures it is £120 million, that is £10 million a year for the licence period. I think it was £10 million a year that the Secretary of State quoted for example last week. Funding that we have always felt is actually absolutely critical to the build-out and conversation to Digital Britain. The commercial sector is absolutely happy to pay its way to the extent that the build-out is commercially viable but, after that, there is a clear public policy imperative. If the Government and Parliament decide that it is important to have a dedicated transmission structure for radio, that will be a public policy decision and it will need funding. That said, we believe that funding is very affordable. If you take that £100 million number, we believe that, for example, the BBC would save much more than that over the period of the 12-year licence just on what it will save on FM transmission alone, so there is a straightforward business proposition. Another way to think about the £100 million over a 12-year licence with the current Licence Fee settlement for the BBC at around about £3.5-£3.6 billion a year is that over 12 years that is £43 billion. The £100 million infrastructure cost for DAB radio is less than a quarter of one per cent of what the BBC’s income will likely be over the next 12 years. So it is eminently affordable if there is a public policy decision that it is important to do that build-out.

Chairman: Those two arguments suggest that you are looking for the BBC to pay for this.

Mr Harrison: We have said very clearly and very fairly that we are absolutely happy to pay our fair share in our way to what is commercially viable.

Chairman: What does that mean?

Mr Harrison: That means that we have already put our hands in our pockets substantially to build out coverage on a local and a national basis as far as we judge is affordable. I think realistically, given the state of the sector, the vast majority of the cost going forward, which is primarily designed to meet the BBC’s obligations of universality rather than the commercial sector’s obligations of viability, should rest with the BBC.

Chairman: So whilst RadioCentre is keen to move ahead with the digital upgrade, the economics of your sector at the moment means that you cannot really afford to put any more money into it?

Mr Harrison: We believe that transmission coverage build-out is axiomatic; it is one of the criteria to effect switchover. We cannot afford it but we absolutely believe the BBC can.

Philip Davies: Andrew, on this part can I ask you about how representative your view is of the industry as a whole? It was over this issue it seems more than any other that UTV Radio quit the RadioCentre and said that it felt that it was no longer representing the interests of the wider industry and gave too much power to its biggest member.

Mr Harrison: Yes, UTV did say that. Scott Taunton, the UTV Radio managing director, actually represented the commercial radio industry with me on the Digital Radio Working Group through all the per-work that was done for Digital Britain, and so they have been intimately involved. To be fair to UTV’s position, they have a particular reservation over the date and the timing for digital, but to be fair to the Digital Britain Report, and indeed we await the clauses of any potential Bill because it is not yet written, there has never been a formal switchover date actually agreed. Although, for example, I think Scott in his Guardian article yesterday talked about a 2015 date being farcical, that date has never been set. What have been set are two consumer-led criteria that have to be hit and then a transition period after that before we all migrate. As Travis said earlier, the majority of opinion across the sector, and certainly across my members and representing my board, is that we need now to put our foot on the gas and work hard to deliver the criteria. Inevitably, there is going to be a spectrum of views with different businesses in different places in terms of their own business models as to the urgency or not they see behind that. UTV are absolutely right to have their own position. They are more at the tail end of the timing.

Philip Davies: UTV did not just say that they had a different position to you. They said something a bit more fundamental than that that they felt that you were no longer representing the interests of the wider industry. It was not just as if they had a disagreement. They were indicating that there were others in the sector who shared their view. Do you accept that there are many others or some others in the sector that would share their view?

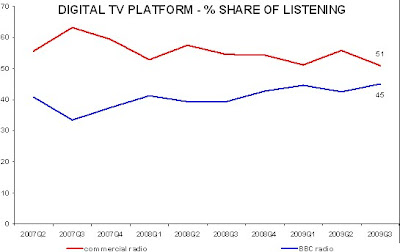

Mr Harrison: I would absolutely accept that we are a broad church and there is a breadth of opinion. I represent large and small stations, local and national, rural and metropolitan, so there is a breadth of opinion. To give you an example of that, our other major national station member that is on AM is Absolute Radio and they believe that the timing for digital should be sooner rather than later. They already have over 50% of their listening on digital platforms, one way or another, so they would move sooner. I have a number of digital-only stations in membership, stations like Jazz and Planet Rock, which clearly are already digital-only and would like to be in the vanguard. Inevitably, there is a spectrum of opinion and we try our best to reflect the overall views. The truth is that it is very unfortunate that UTV have left membership but we continue to represent the vast majority of the sector and its stations and will continue to try to steer a path, helping Government and helping the regulator through this tension.