Nobody likes to see radio stations close. Nobody likes to see committed radio staff thrown out of their jobs. Nobody likes to see the population of a town deprived of having their own local radio station. Nobody likes to see local businesses of any type disappear.

Abbey FM in Barrow closed at 3pm yesterday after two years on-air, with six full-time staff and six freelancers made redundant. The station was jointly owned by The Local Radio Company [TLRC] (35%), CN Group (30%), and Martyn Rose Ltd. (35%).

Station manager Amanda Bell said yesterday:

“This also means that Barrow will never again have its own radio station. There won’t be another licence issued for Barrow. It was very, very sudden. We had the support and backing of all three shareholders until three weeks ago, when TLRC withdrew their support, which forced the hand of the other shareholders. I was only told of their decision at 12.30pm today. We were doing extremely well and heading towards making profits until July last year and then the economic situation got worse……”

Robin Burgess, CN Group chief executive, said yesterday:

“Abbey started broadcasting in late 2006 but unfortunately has never been profitable. In the present economic climate and, in particular, the effect the recession is having on media revenues, the directors saw no realistic prospect of the station getting into profit in the foreseeable future.”

But can this closure so easily be credited solely to the advertising downturn? Or is its closure a symptom of a much wider issue concerning the licensing of small commercial radio stations in the UK? Both Amanda and Robin mentioned the station’s lack of profitability – what is the real problem?

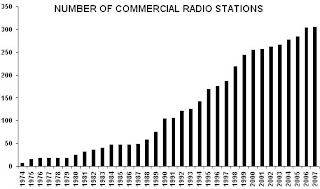

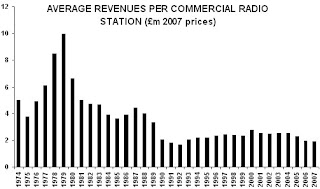

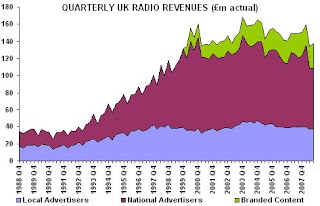

Abbey FM served an area of only 84,000 adults. It was one of the 21 local commercial radio licences that Ofcom has awarded to date which serve populations of 250,000 or fewer adults. Ofcom’s own research found that local stations serving between 50,000 and 150,000 adults make an average annual loss of £20,000. However, by continuing to licence new stations serving populations as little as 39,000 adults, Ofcom has created even more local stations that are mostly condemned never to make an operating profit. Worse, new stations tend to cannibalise the audiences of existing local commercial stations heard in the same area.

The problem is that, in its radio licensing system, both Ofcom and most of the applicants for its licences embark upon a merry dance together that has little basis in real world radio economics. Ofcom appears to advertise new licences such as Abbey FM’s without any prior analysis of whether the local economy, Barrow in this case, can produce enough new advertising revenues to support a new local station.

Licence applicants submit to Ofcom a business plan (in confidence) and the imperative is almost always to make the figures fit so that the station looks as if it will break even by the end of its third year on-air. This is the greatest stress point for truthfulness. The smaller the station, the less likely it will be (in reality) to break even in Year Three. To make this breakeven work ‘on paper’, the smaller the station, proportionately the greater its projected audience has to be (because radio is largely a fixed cost medium).

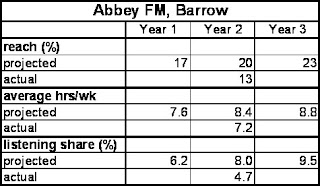

Abbey FM acknowledged in its application that “a long-term investment strategy is what is required for this station; there are no short cuts to sustainable profitability”. However, its forecasts for the station’s performance were the outcome of market research which concluded that “66% of all radio listening adults in Barrow would be definitely, very likely or fairly likely to tune in to a new station….” The application then asserted that “a combination of experience and prudence has dictated that we forecast reach of 17% in year 1 rising to 23% by year 3”.

This is voodoo forecasting, where the audience figures are often calculated as the last part of the puzzle to be solved (after profits, revenues and costs), rather than making them the cornerstone of the business plan. This is not intended as a specific criticism of the Abbey FM application. It is an inherent failing of most radio licence applications submitted to Ofcom. The bigger problem is that, if you were to honestly appraise the potential audience of such a small station, the financial forecasts would be unlikely to ever show an operating profit. Put simply, a radio station this small is often not a going concern. Yes, Abbey FM had failed to achieve its targets, but those targets were probably fictional anyway.

However, the merry dance continues because Ofcom exists to licence new stations (even if they are likely to fail), and most radio groups think they exist to win radio licences (even if they are likely to fail). As a consequence, by opening more loss-making stations, the overall profitability of the UK commercial radio sector becomes increasingly eroded, until the profitability of an entire group is weighed down by the number of loss-making stations it is trying to support.

Ofcom often comes close to acknowledging that these small local stations are destined to fail when it explains why it has awarded their licences. For Abbey FM, Ofcom said that:

“…..the committee felt that the backing of three shareholders with, collectively, extensive and current experience of operating smaller radio stations enhanced the likely ability of Abbey FM to maintain its proposed service. The group’s business plan was considered to demonstrate a good understanding of the local market and of the issues that the new station may face, and the ability to save costs through resource-sharing with nearby stations was felt to further enhance the strength of Abbey FM’s financial proposition.”

In other words, this new station will need to be subsidised for an indeterminate number of years by other, profitable stations owned by the same group(s). This is why, almost on every occasion, new small, local stations are awarded by Ofcom to owners that already have radio stations, often in a nearby area. In Abbey FM’s case, CN Group’s station The Bay already enveloped the entire Abbey FM area. Would it not have made more sense for Ofcom to offer the citizens of Barrow a local opt-out of The Bay, so they at least would benefit from some of their own local programming? As it is, they are now left with nothing at all.

So who is to blame? Firstly, Ofcom for having advertised small local licences in the first place which are condemned never to be profitable. A business is not a business unless it covers its costs. Secondly, radio groups who (collectively) have applied for every radio licence advertised by Ofcom. There has not been a single licence, however small, that has not attracted at least one applicant. Thirdly, Ofcom (again) for not having the guts to NOT award a licence to any applicant in an area, where it is plainly obvious that none of the applicants are telling the truth in their business plans and stand almost no chance of ever making a profit. Fourthly, radio groups (again) for seeing each licence win as a way to enhance their balance sheets, regardless of whether those licences can ever be made into profitable businesses.

So the merry dance between radio owners and Ofcom (and its predecessor) has led us to where we are today. Sadly, Abbey FM is merely the first of many local stations that will have to close in 2009. This is not the way it should be. I did not spend the 1970s and 1980s campaigning for MORE local radio stations (ComCom, CRA, etc) to see them close down like this. However, I don’t know of a single, small radio group that is presently not willing to discuss selling some or all of its stations. In my own backyard, there is a local station which is likely to sell soon for £1, or close. Never before have there been so many sellers and yet a complete lack of buyers for local radio.

Abbey FM, RIP. The losers are the citizens of Barrow. The UK radio licensing system has failed them. Why does it appear that no one is willing to step forward and take responsibility (just like the financial sector) for such institutional failures?

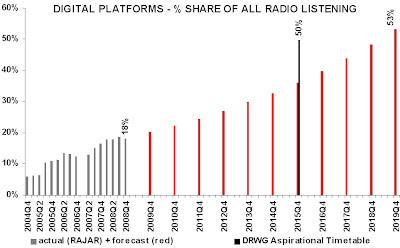

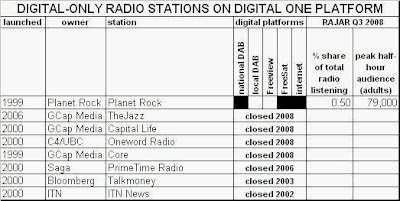

It hardly inspires confidence in the Digital One DAB platform that Global Radio’s predecessor, GCap Media, closed three of its own digital-only stations carried on its platform last year, and sold Planet Rock to an entrepreneur with no other radio interests. Neither is it a good advertisement for Digital One that its

It hardly inspires confidence in the Digital One DAB platform that Global Radio’s predecessor, GCap Media, closed three of its own digital-only stations carried on its platform last year, and sold Planet Rock to an entrepreneur with no other radio interests. Neither is it a good advertisement for Digital One that its