Most of the current debate on the challenges facing DAB radio seems to be focused on ‘supply side’ issues, such as upgrading existing DAB transmitters, making DAB radio receivers available in cars and the creation of another national DAB multiplex. Surprisingly little of the talk is about the ‘demand side’ issues facing the DAB platform. What are consumers demanding from DAB radio? And how great is that demand?

There are two types of consumer demand for DAB: the demand for content broadcast on the DAB platform, and the demand for DAB radio receiver hardware. The two are inextricably linked. Consumer demand for DAB hardware is largely a function of demand for DAB content. You will only want to buy a DAB radio if you believe there is something interesting enough to listen to on it. Let’s examine some of the available data on these two issues.

Consumer demand for DAB content

Nobody is going to be motivated to spend money on a DAB receiver for listening to the radio if the platform only offers the same content already available to them on analogue receivers. Therefore, it must be the exclusive digital-only content available on DAB (and other digital platforms) that will persuade consumers to both use the DAB platform and to purchase a DAB radio receiver.

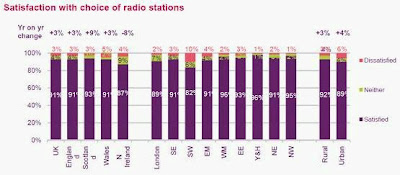

So how dissatisfied are consumers by the radio content choices (the range of radio stations) available to them on existing analogue radio receivers? Ofcom research shows that 91% of adults are satisfied with the existing choice of radio stations offered to them (see chart below), a proportion that has risen in recent years. This demonstrates that dissatisfaction with existing radio provision is extremely low, making it very difficult for any new platform to attract a substantial audience by offering content that will gratify consumers’ few unsatisfied demands.

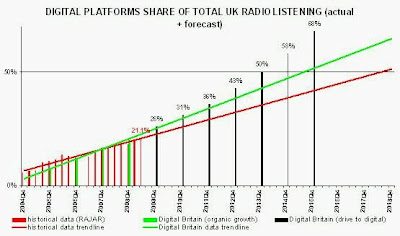

[In case you are wondering if the increasing satisfaction with radio stations might be a direct result of the exclusive digital-only stations already offered on the DAB platform, it is worth noting that only 3.9% of hours listened to radio are attributed to digital-only stations [RAJAR 2009 Q2].]

Ofcom data shows that the average consumer listens to very few radio stations. Two thirds of the population listen to only one or two different radio stations in an average week, and the majority of these two-thirds listen to only one station. So, not only are the overwhelming majority of consumers satisfied with their existing choice of radio stations, but most people listen to a very narrow menu of stations.

These phenomena are not the outcome of consumers only being offered a limited choice of radio stations on the analogue platform. Ofcom data demonstrates that, in addition to the 5 BBC radio stations and 3 commercial radio stations available nationally on analogue radio (with near universal coverage) in the UK, there are a significant number of local radio stations available to consumers in most areas of the UK. The average consumer in the UK has a choice of 8 national radio stations and 6 local radio stations.

This existing wide choice of radio stations makes the plan for migration to digital platforms very different for the radio medium than it is for the television medium. In the UK, only four (five in some areas) TV stations are available via analogue, making the wider choice available on digital platforms seem very attractive to consumers. Whereas, in radio, an average 14 stations are available to consumers on analogue, and these are already satisfying the vast majority of consumer demands. As a result, there is only a very tiny untapped consumer market for radio content not already available via analogue.

This is demonstrated by analysis of the largest UK radio market, London, in which consumer choice is at its greatest. There are 29 licensed radio stations available on the analogue platform in London (excluding community radio and out-of-area stations), but the top 3 stations account for just under a third of all radio listening in London, and the top 6 stations account for almost half of all radio listening. The radio market in London, as in most of the UK, is dominated by a tiny number of mainstream stations, whilst the remaining radio offerings comprise a ‘long tail’ that fulfils more specialist consumer needs.

The dramatic consumer skew towards mainstream radio means that, even in a radio market as developed as London, it proves difficult for incremental, digital-only stations to draw significant amounts of listening. The most listened to exclusively digital radio station in London is BBC 1Xtra, which ranks 22nd and attracts only a 0.5% share of listening in the market [RAJAR 2009 Q2]. 1Xtra’s content (UK black music) is barely duplicated by any other legal radio station available in London, and yet its ‘success’ remains slight in a very multicultural market that is already crowded with myriad radio options for consumers. The recent decision by London station Club Asia to enter administration, combined with the closures earlier this year of South London Radio and Time 106.8, demonstrate the challenge for stations to find a ‘monetisable’ audience in London, even on the analogue platform.

It might be easy to assume that Londoners, offered the widest selection of radio stations on the analogue platform, would be more satisfied with their choice in comparison with consumers in other, less well served parts of the UK. The surprising result from Ofcom research is that Londoners are, in fact, less satisfied with their choice of radio than most other parts of the UK. The chart below (extracted directly from a recent Ofcom report) demonstrates that satisfaction with existing radio provision is almost evenly spread across the whole UK, but consumers in London and Northern Ireland are the least satisfied.

In summary, radio in the UK has been a victim of its own success. The universal availability of a range of both BBC and commercial ‘national’ stations, combined with the extensive choice of local stations available in most markets, mean that consumers are already relatively spoilt for choice on the analogue radio platform. There is very little unsatisfied demand for radio content because the UK already has such a comprehensive choice of radio content on offer. As a result, any new radio platform (DAB, satellite, online, etc) is going to find it hard to compete with the high quality and diverse choice of what is already on offer.

This was always going to make it tough for the DAB platform to entice consumers to purchase DAB receivers as anything other than a ‘replacement’ for their existing analogue radios. Unfortunately, the natural replacement cycle for radio receivers is so slow (maybe ten years or more) that it will never prove sufficient for a complete UK digital switchover to be co-ordinated for radio, as is happening in the television market. The UK has some of the best radio in the world – ironically, this has been our digital downfall.

Consumer demand for DAB radio receivers

As noted earlier, consumer demand for DAB hardware is largely a function of demand for DAB content. You will only want to buy a DAB radio if there is something interesting enough you want to listen to on the DAB platform.

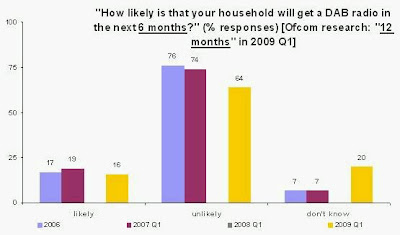

Ofcom research demonstrates clearly the lack of interest amongst consumers in purchasing DAB radio receivers. In this year’s survey, only 16% of consumers (without a DAB radio) say they are likely to purchase a DAB radio within the next 12 months. Two years ago, 19% said they would be likely to purchase a DAB radio within the next 6 months. This is very bad news for manufacturers and retailers of DAB radios. Worse, this year not only do 64% of consumers say they are unlikely to purchase a DAB radio, but 20% say they don’t know – a demonstration that a DAB radio is far from being a ‘must have’ gadget on consumers’ wants lists.

The data for current levels of DAB radio receiver ownership are not very helpful in determining the demand for DAB radio receivers. The quarterly survey by RAJAR found in 2009 Q1 that 32.1% of adult respondents claimed to own a DAB radio. However, the annual Ofcom survey found in the same quarter that 41% of adult respondents claimed to have a DAB radio in their household. This disparity between the results from RAJAR and Ofcom would appear to be widening over time.

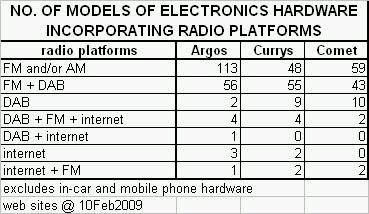

The uncertainty in the data regarding ownership levels of DAB receivers is not surprising, given the evident level of consumer confusion. Firstly, many radios on the market have the words “digital” or “digital radio” written on them, meaning that they either incorporate a digital clock (for radio alarm clocks) or that they offer ‘digital’ tuning of analogue wavebands, despite them not offering DAB reception. Secondly, the majority of ‘DAB radios’ presently on sale in the UK offer DAB reception in combination with analogue radio and/or internet radio. When DAB radio receivers were first introduced a decade ago, all the models offered were DAB-only. Nowadays, it is harder to find a DAB-only model in shops. Earlier this year, I surveyed the radio hardware on sale from UK retailers (see chart below) and found that the most common DAB consumer proposition is now an ‘FM + DAB’ radio.

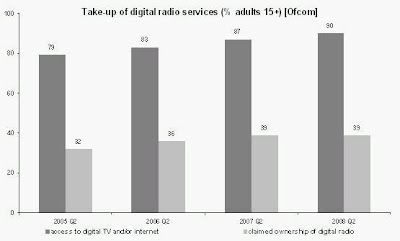

In its latest consumer research on take-up of digital radio, Ofcom said that the result of its survey (see below) “highlights the continued lack of awareness among consumers of ways of accessing digital radio”. Consumers have low awareness of their ability to already access digital radio, and It appears that the words “digital radio”, “digital audio broadcasting” and “DAB” are not yet precisely understood. This uncertainty makes the results of market research about ownership levels of DAB radio hardware somewhat unreliable.

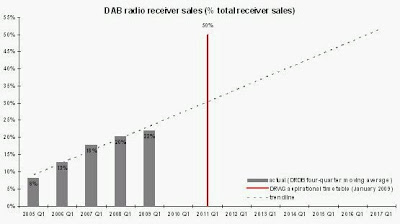

One of the targets set by the Digital Radio Working Group at the end of 2008 for the implementation of digital radio was that DAB radios should reach 50% of radio receiver sales by volume by the end of 2010. However, if the current rate of growth continues, this target is unlikely to be reached until 2016 (see chart below).

Besides, this target is largely irrelevant to digital switchover because it seems to assume that consumers are making a definitive choice between the purchase of a DAB radio or an analogue radio. In fact, as the earlier chart shows, the majority of DAB radios presently offered by retailers also include FM radio. Although the DRDB data states that 22% of radios sold in the UK incorporate DAB, the vast majority of those include FM too. So, for every 100 new radios sold, you are probably adding to the UK’s inventory of receivers between 95 and 98 new FM radios, at the same time as adding 22 new DAB radios. In other words, the household penetration level of analogue radio receivers is barely diminishing at all, a fact that will ensure that FM broadcasting remains as vital to our radio system as it has always been.

In summary, the DAB platform seems to be developing slowly as a supplementary platform to existing analogue radio reception. Far from DAB radios ‘replacing’ analogue radios, the overwhelming majority of new radios purchased in the UK are still analogue-only. The remainder are mostly DAB/analogue combination receivers. In this way, DAB has much in common with ‘Long Wave’ radio, where consumers for a long time were offered a choice of ‘FM+AM’ or FM+AM+Long Wave’ receivers in retail stores. Like Long Wave, for a minority of consumers DAB may be a ‘must have’ when purchasing a new radio, but for the majority it is merely an optional extra whose purchase is likely to be very dependent on the comparative prices of available options.

Conclusion

The publicly available data on the demand for DAB is not particularly encouraging for the platform’s future. Much of the implementation of DAB to date in the UK has focused on ‘supply-side’ issues, without seeming to determine whether there is sufficient demand from consumers for new content, and without determining whether that new content would prove sufficiently attractive to lure consumers into shops to purchase DAB radios. Ironically, it appears that if our existing system of analogue radio broadcasting had been less well developed in terms of both the range of available content and its near universal delivery, DAB might have been better able to address any pent-up demand from consumers. As it is, the majority of consumers seem very content with their existing radio options. Our pursuit of excellence in radio over the last 80 years has created something we can be proud of – but it has also made it hard for it to be bettered by a ‘new’ system such as DAB.

[For more data on the challenges facing digital radio in the UK, check out a presentation I made to the European Broadcasting Union Digital Radio Conference in June 2009]